Claude Lorrain

French, 1604 - 1682

French painter, draughtsman, and etcher who specialized in landscape. He was born at Chamagne (Toul) in the duchy of Lorraine. He trained initially as a pastrycook and it was probably in that capacity that he moved to Rome, maybe as early as 1617. Shortly afterwards he seems to have turned to painting and moved to Naples, working there for two years under the German artist Goffredo Wals (c. 1600–38/40). This was followed by further training back at Rome with Agostino Tassi who specialized in painting landscape, coastal scenes, and illusionistic architecture. Claude returned briefly to Lorraine in 1625 and was assistant at Nancy to the court painter Claude Deruet whose figure style made a lasting impact on him. He may also have met Callot and copied several of his etchings. By 1627 Claude was back at Rome and he settled there for the rest of his life. He now fell under the influence of the northern painters living in the city who specialized in scenes of everyday life, often set against scenes of ancient ruins: Bartholomeus Breenbergh, Herman van Swanevelt (c. 1600–55), with whom he shared lodgings, and Pieter van Laer, one of the Bamboccianti artists. Above all he responded to Paul Bril's imaginary mythological landscapes.

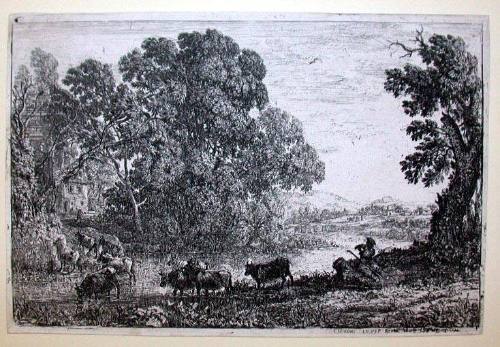

Claude's great achievement as a landscape artist was to transform the Venetian Renaissance concept of the pastoral landscape into a more natural but no less poetic genre, based on his capacity to perceive Rome and its surrounding landscape with the eyes of a foreigner, intoxicated by its classical associations and the Italian light. Conscious through close observation of nature of changing patterns in the landscape, especially at sunrise and sunset, he found a beauty that was atmospheric and objectively perceived as well as poetic and idealized. His earliest Roman work includes a Pastoral Landscape (1629; Philadelphia Mus.); an etching, The Storm (1630); and The Mill (Boston, Mus. of Fine Arts), which successfully combines a precision of naturalistic observation with a well-ordered and idealized composition, these elements unified and the mood intensified by the early morning light that is filtered through the trees, from the left.

Claude's capacity for observation was nurtured by his frequent sketching expeditions, both in the immediate countryside around Rome, along the left bank of the Tiber, and along the ancient Via Appia, and further afield at Tivoli or Subiaco. The survival of hundreds of drawings in pen and ink, wash and black chalk, recording open-air views, trees, rocks, plants, and streams, and exploring patterns of light and shade and contre jour effects of trees silhouetted against the sun, confirm the impression that Claude used drawings made out of doors as an essential point of reference when back in the studio. He may also have found the process of making the drawings served to focus his mind and memory on both the changing and the permanent aspects of the natural world. The outcome is reflected in such pictures as Landscape with a Goatherd (1637; London, NG) and View of La Crescenza (New York, Met. Mus.). The German writer Sandrart suggests Claude also made oil paintings or oil sketches on the spot, although apparently none has survived.

One of Claude's most striking innovations was to include the sun as the direct source of light at the focal point of his paintings, thereby throwing into relief all the features of the foreground and middle ground. Although this idea probably originated from his sketching out of doors, it was a technique he employed most effectively in his more contrived scenes of harbours and seaports, which became one of his most celebrated subjects, inspired perhaps by Tassi's seascapes (for instance, Rome, Doria Pamphili Gal.). Among Claude's earliest pictures of this kind is the Harbour Scene (1634; St Petersburg, Hermitage) and he persisted with this category of subject matter in the Seaport with Setting Sun (1639; Paris, Louvre), the Seaport with the Embarkation of S. Ursula (1641, London, NG), and many other works.

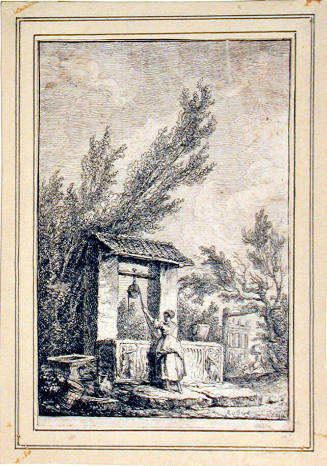

By the late 1630s, Claude had begun to introduce figures drawn from mythological or biblical sources to add gravitas or emotional force to his landscapes. At the same time his approach to nature became less detached and he imposed a new sense of grandeur through a more complex spatial structure, emulating the classicizing landscapes of Annibale Carracci and Domenichino. A series of four Landscapes of vertical format, commissioned by King Philip IV of Spain in 1639 for the Buen Retiro, mark a decisive step in this direction. They represent The Finding of Moses and Tobias and the Angel, from the Old Testament, together with the Embarkation of S. Paula and the Burial of S. Serapia. Claude took advantage of the required vertical format to allow trees and architectural columns a dominant place in defining the structure and perspective of the designs, and the figures too are heroically conceived.

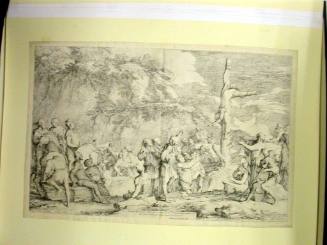

As Claude's style gravitated towards a more idealized vision of nature, his choice of subject matter also brought a new level of empathy with the ancient world. His Landscape with Narcissus and Echo (1645; London, NG) reflects the lyrical description in Ovid of the spot where Narcissus fell in love with his own reflection in a ‘clear pool with shining silvery waters’. Equally, his Landscape with Procession to Delphi (1650; Rome, Doria Pamphili Gal.) evokes the temple of Apollo but in an imaginary reconstruction that transcends nostalgic concerns with the ruins of Antiquity. This elevated tone continues during the next decade with such heroic large scale canvases as Landscape with Apollo and the Muses (1652; Edinburgh, NG Scotland); Landscape with the Adoration of the Golden Calf (1653; Karlsruhe, Kunsthalle), where the figures are inspired by Raphael's fresco of the same subject in the vault of the Vatican Loggias; a Coast Scene with Acis and Galatea (1657; Dresden, Gemäldegal.), based on Ovid. In some respects, Claude appears to be emulating the heroic style of his compatriot Nicolas Poussin, especially in his concern for scholarly detail, noble subject matter, and conceptual clarity. Yet there is a fundamental gulf that separates them. For Poussin, in his maturity, landscape is a vehicle for suggesting or reflecting mood and clarifying his subject matter; the figures always remain dominant. With Claude, on the other hand, his northern eye for natural detail and atmospheric effects dominates every painting, and the figures, even when exceptionally large, as in the Apollo and the Muses, are always secondary to his vision of nature.

Some of Claude's very late work achieves an epic or heroic quality, most notably in his Landscape with Aeneas at Pallanteum (1675; Anglesey Abbey, Cambs.), where the landscape matches the description in Virgil's Aeneid. Other work, particularly the Enchanted Castle (1664; London, NG), which shows Psyche waking outside the Palace of Cupid in anticipation of the consummation of her passion, creates a mood of mystery and romance that anticipates 19th-century Romanticism and transcends Claude's otherwise quite limited emotional range.

During his lifetime Claude enjoyed enormous success and as early as 1634 was apparently forged or plagiarized by Bourdon. Such incidents may have prompted him to keep his Libro d'invenzioni or Liber veritatis, recording his designs and the names of buyers (now London, BM). Far more than Poussin, he was patronized by the Roman nobility and above all by Pope Urban VIII. Of the cardinals, Rospigliosi and Massimi supported them both. Yet Claude's work also appealed to contemporary French collectors as well as to travellers, including the Marquis de Fontenay Mareuil; and it could without exaggeration be claimed that, through the choice of locations with classical associations in his landscapes, he pioneered the concept behind the Grand Tour, and the itineraries on which it would be based in the 18th century. Later artists, from Britain in particular, would transform his intense vision into a more relaxed topographical genre, or more literary and nostalgic capricci, or even into landscape gardens; but the original idea, the close association of natural landscape with the ruins of the classical past and the ancient but still vibrant poetry of Ovid, Virgil, and Horace, was first conceived from very different standpoints, by Poussin and Claude.

Hugh Brigstocke. Oxford University Press, 2001. Oxford Reference Online. Oxford University Press. 6 March 2012

Person TypeIndividual

Italian, c. 1610 - 1665