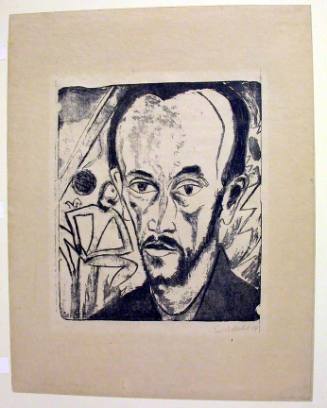

Max Klinger

German, 1857 - 1920

German painter, printmaker, sculptor and writer. He was one of the most versatile German artistic personalities of the turn of the 20th century and was especially celebrated for his cycles of prints, which were influential.

1. Early paintings and major print cycles.

He studied with the genre painter Karl Gussow (1843–1907) at the academies in Karlsruhe and, later, Berlin. In 1879 he spent a period studying in Brussels with the Symbolist painter Emile Wauters. Such early paintings as Attack at the Wall (1878; Berlin, Alte N.G.) reveal his regard for Realist and Impressionist painters in France. He also started making prints at this time, producing the cycles (all etching and aquatint) Salvation of Ovid’s Victims (1879; see Varnedoe, nos 3–4), Eve and the Future (1880; v 5–10), Intermezzi (1880; v 11–15), A Glove (1878–81; v 18–27) and the book illustrations to Cupid and Psyche (1880; v 16–17). The Glove cycle anticipates Surrealism in its combination of reality and dream and reflects the contemporary beginnings of psychoanalysis. It is in his prints that Klinger’s analysis of gender conflict in society, a subject of increasing concern in the late 19th century, comes to the fore. As in the work of Edvard Munch, a large amount of Klinger’s work is devoted to the themes of sexuality, love and death. The cycle Eve and the Future introduces a highly individual interpretation of the biblical Fall.

In 1883 Klinger was commissioned to decorate the Villa Albers in Steglitz, Berlin (paintings now in Hamburg, Ksthalle, and Leipzig, Mus. Bild. Kst.). In such paintings his admiration for Impressionist painting and the work of Arnold Böcklin (whom he met in 1887) is especially clear. In the Villa Albers, Klinger realized his ideas of Raumkunst, derived from Pompeian mural art and iconographically inspired by Böcklin’s mythological scenes. In 1883 he made his first visit to Paris, where he gained a closer knowledge of the work of Francisco de Goya and Gustave Doré (already both influences on his prints), as well as Old Master paintings and the work of such contemporary painters as Pierre Puvis de Chavannes. During his stay in Paris, Klinger developed an interest in the painting of the Renaissance, coming to believe that the starting-point of all art must be the naked human figure. From this time on, his paintings are a strange mixture of extreme naturalism and an idealism devoted to both the ancient world and Christianity.

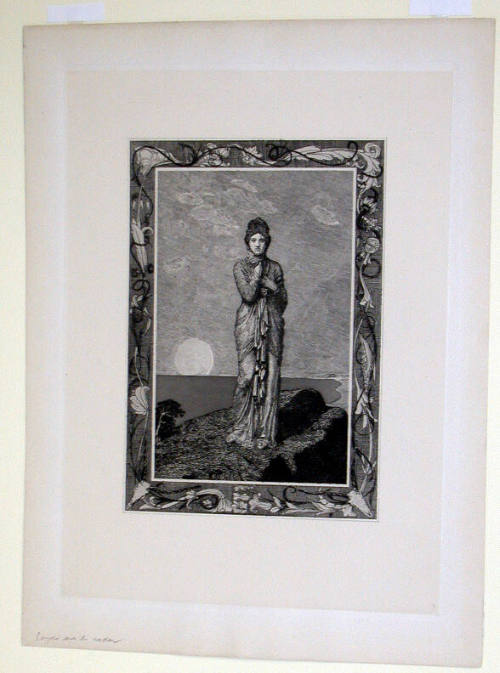

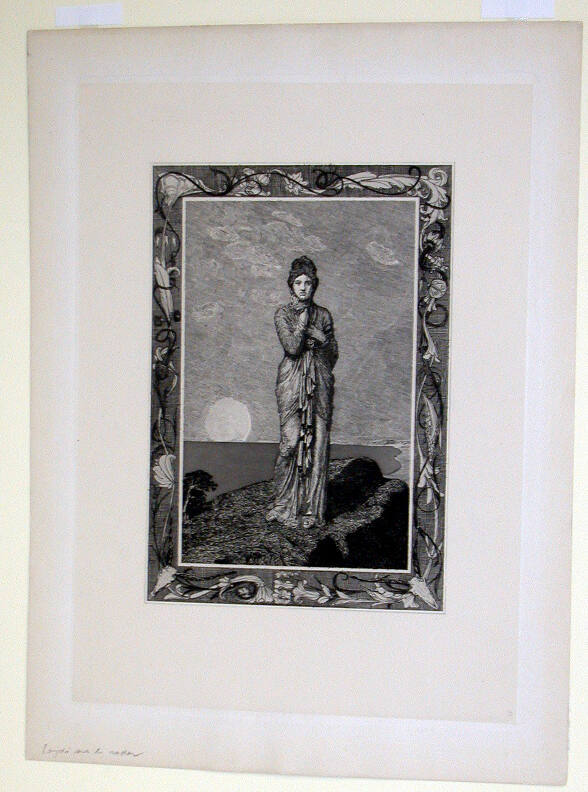

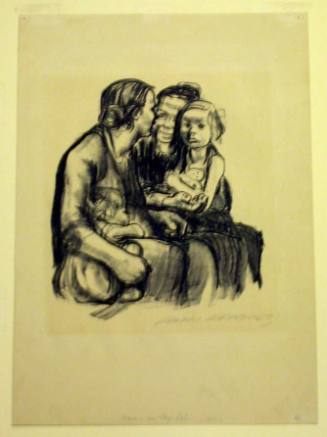

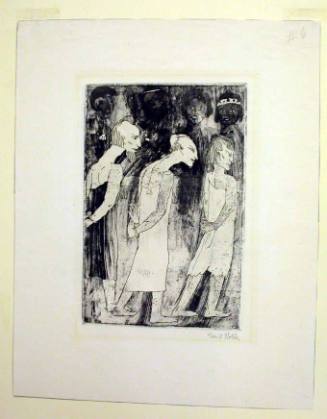

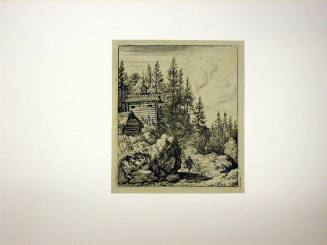

Between 1883 and 1894 Klinger produced his most important cycles of prints: A Life (etching and engraving, 1883; v 29–37), Dramas (engraving, 1883; v 38–45), A Love (etching and aquatint, 1887; v 46–55), Of Death, Part I (etching and aquatint, 1889; v 56–65) and Brahms Fantasy (etching, engraving, aquatint and mezzotint, 1894; v 66–70). A Life vividly depicts the social causes of prostitution and treats the story of a fall from virtue almost from the woman’s point of view. A commentary on the development of the plot is provided in symbolic and allegorical images. In the cycle Dramas he shows the social conflicts of the Berlin suburbs driving people to suicide or infanticide (as in the sheet A Mother) or to revolutionary actions (March Days). In A Love, which was dedicated to Böcklin, he denounced the double standard of bourgeois morality. The meditative cycle Of Death, Part I is strongly influenced by the philosophy of Arthur Schopenhauer and Friedrich Nietzsche (as is the later Of Death, Part II from 1909). The Brahms Fantasy cycle , dedicated to the composer Johannes Brahms, is a pictorial rendering of his songs and seeks to unite music, language and image in a Gesamtkunstwerk. Here, Klinger refers to the myth of Prometheus, a symbol of the artist–genius whose failure in the last sheet of the cycle points to the increasingly insignificant role of the artist in society.

During a longer stay in Paris (1885–6) Klinger began to plan various sculptural projects and painted the Judgement of Paris (1885–7; Vienna, Ksthist. Mus.). In its monumental proportions, architectonic arrangement and sculpturally decorated frame, it clearly required presentation in a museum. It was also held to be provocative, since ancient myth was not aesthetically distanced by being clothed in classicist formal language but rather presented as a highly charged confrontation of the sexes. From 1888 to 1893 Klinger lived in Rome, where he became increasingly interested in the art of the Italian Renaissance and that of antiquity. In 1890 he painted The Blue Hour, a Crucifixion (both Leipzig, Mus. Bild. Kst.) and a Pietà (Dresden, Gemäldegal. Neue Meister, destr.; see 1970 exh. cat., p. 37). In these last two he attempted to create new content for Christian themes through psychological intensification, placing emphasis, for example, on the mother–son relationship. The Crucifixion caused a scandal because of Christ’s total nudity.

In 1891 Klinger published the essay Malerei und Zeichnung, in which he discussed problems of style, form and content in the visual arts, referring to Gotthold Ephraim Lessing’s essay Laokoon (1766) and the writings of Richard Wagner on the idea of the Gesamtkunstwerk, and argued for a fundamental distinction between painting and the graphic arts. For Klinger, painting was to reflect the beauty of the visible world, while prints had the function of showing ‘the dark side of life’; they should express the deepest convictions and emotions of the artist and evoke ‘associations’ in the mind of the viewer, as poetry or music might.

2. Sculpture and later paintings.

In 1893 Klinger moved to Leipzig, where his studio became a centre of the city’s cultural life. At this point he embarked on a series of sculptural works, including New Salome (1893), Cassandra (1895; both Leipzig, Mus. Bild. Kst.), Drama (1904; Dresden, Skulpsamml.) and a monument to Brahms (1909; Hamburg, Musikhalle). Klinger’s sculptural work is informed by his effort to revive the technique of polychrome and polylith stone sculpture (a combination of different coloured stones and materials), as recorded in the example of ancient cult statues. He used this approach for the three female half-length figures New Salome, Cassandra and the portrait of his lover, the author Elsa Asenijeff (c. 1900; Munich, Neue Pin.). His Salome has a challenging directness and confident decisiveness, in contrast to contemporary interpretations that characterized her as the epitome of the femme fatale with ethereal and morbid traits. The head of John the Baptist leans against her on one side with that of an older man on the other. In the figure of Cassandra Klinger shows the ancient prophetess in a state of intense psychological strain resulting from intellectual insight, combined with an inability to act: her left hand lies, as if soothing, on her clenched right fist.

The technique of polylith stone sculpture found its most consistent expression in Klinger’s monument to Beethoven (completed 1902; Leipzig, Mus. Bild. Kst.), on which he had worked for more than 20 years. The composer, whose figure is made of white marble with clothing of red alabaster, sits like an Olympian god, with an eagle at his feet, on a bronze throne decorated with gold, ivory, glass, jewels and mother-of-pearl. While the use of valuable material anticipates aspects of Jugendstil, the figure itself recalls Auguste Rodin’s Victor Hugo (plaster version, Meuden, Mus. Rodin) and The Thinker (bronze version, Paris, Mus. Rodin). The ceremonial installation of the monument at the 14th Vienna Secession in 1902 also involved the architect Josef Hoffmann, the painter and decorative artist Gustav Klimt and the composer and conductor Gustav Mahler.

Klinger’s paintings from after 1893 were on an increasingly monumental scale. Christ on Olympus (1897; Leipzig, Mus. Bild. Kst.), combining painting and sculpture, was designed as a Gesamtkunstwerk, and in it he explored his dream of the meeting of Christian and ascetic with ancient and sensual cultures. A mural for the Universität Leipzig, The Bloom of Greece (1907–9; destr., see Winkler, pl. 244), was a programmatic history painting intended to emphasize the spiritual similarities of Greek and German culture. His last mural, Work, Wealth, Beauty (1918; Chemnitz, Altes Rathaus), incorporates images of modern industry and idealized beauty. Print cycles from Klinger’s later years, including Of Death, Part II (engraving, etching and aquatint, 1909; v 71–4) and Tent (etching and aquatint, 1915; see 1984 exh. cat., nos 289–334), also testify to his continued inventiveness both in content and technique.

From the 1890s Klinger won public acclaim, becoming a member of the Akademie der bildenden Künste, Munich (1891), Akademie der Künste, Berlin (1894), and Professor of the Akademie der Graphischen Künste in Leipzig (1897). In 1892 he joined the Gruppe XI to protest against Berlin’s conservative art policies and from 1897 he was a corresponding member of the Vienna Secession. In 1903 he became Vice-President of the Deutscher Künstlerbund and in 1905 he set up its studio house, the Villa Romana, in Florence. Klinger had no pupils, but his work, in particular his prints, influenced artists as diverse as Käthe Kollwitz, Alfred Kubin, Max Ernst, Edvard Munch and Giorgio de Chirico. Although a celebrated and controversial figure during his life, he was soon forgotten and was fully appreciated again only in the 1970s in the context of a reassessment of 19th-century art. The lasting significance of Klinger’s work lies in its visualization of contemporary social and gender conflicts and its concern with the function of art and the artist in modern society.

Annegret Friedrich. "Klinger, Max." In Grove Art Online. Oxford Art Online, http://www.oxfordartonline.com.proxy.lib.fsu.edu/subscriber/article/grove/art/T046899 (accessed April 27, 2012).

Person TypeIndividual