Andrea Meldolla, known as Schiavone

Italian, about 1520 - 1563

Dalmatian painter, draughtsman and etcher, active in Italy. He belonged to a prominent family who had settled in Zara but were originally from Méldola in the Romagna. He may have been taught painting either in Zara or in Venice by Lorenzo Luzzo or Giovanni Pietro Luzzo, who were active in both cities. According to another theory, he was trained in the Venetian workshop of Bonifazio de’ Pitati, but this would not account for his later proficiency as a fresco painter. As an etcher, he seems to have been essentially self-taught, working initially from drawings by Parmigianino. By the late 1530s Schiavone seems to have been established in Venice. In 1540 Giorgio Vasari commissioned from him a large battle painting (untraced), ‘one of the best [works] that Andrea Schiavone ever did’ (Vasari, 1568). Schiavone’s first surviving paintings and etchings probably date from c. 1538–40; they show that he was strongly influenced by Parmigianino and Central Italian Mannerists in figural and compositional modes, but was also a strikingly daring exponent of Venetian painterly techniques; he employed an equally free technique in etching. Several paintings, for example the large-scale Four Women in a Landscape (priv. col., see Richardson, fig.) and the small-scale Two Men (priv. col., see Richardson, fig.), carry his ‘technique of spots, or sketches’ (Vasari) so far that the subjects have not been identified.

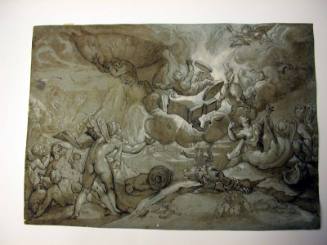

During the 1540s Schiavone developed this style in paintings of increasing size and complexity, such as the Conversion of St Paul (Venice, Fond. Querini–Stampalia) and the organ shutters of David and Daniel (Venice, S Giacomo del Orio). His etchings, too, became increasingly elaborate and technically inventive, culminating in his only signed and dated work, the very large Abduction of Helen (b. 81) of 1547. This combines elements from Giulio Romano’s Battle of Constantine (Rome, Vatican, Sala di Constantino), Titian’s Battle of Cadore (ex-Doge’s Palace, Venice; destr.) and Mannerist engravings of battle scenes with Schiavone’s own inventions in a torrential flow of horses, humans and banners, all fusing with, and submerged in, a dense atmospheric tone. Very close stylistically, and probably close in date, is the painting of the Adoration of the Magi (Milan, Ambrosiana), in which the rhythmic flow is achieved by the deformation of figures and architecture and the assertively liquid texture of the paint. The use of colour is complex and unorthodox, spicing harmony with dissonance.

Schiavone’s principal surviving frescoes (Venice, S Sebastiano, Grimani Chapel) date from c. 1548–50; they are astonishing in their impressionistic use of the medium. The frescoes on the façade of Palazzo Zen, Venice (destr.), may have been contemporary, to judge by Boschini’s vivid description. Schiavone’s paintings of the 1540s translated Mannerist and Parmigianesque elements into an intensely Venetian painterly idiom to novel and compelling effect. They shocked some contemporaries and stimulated others: Paolo Pino (1548) stigmatized Schiavone’s empiastrar (use of impasto) as ‘worthy of infamy’; and in the same year Pietro Aretino, in a letter to Schiavone, both praised his invention and complained of his lack of ‘finish’, reporting that Titian was amazed ‘at the technique you demonstrate in setting down the sketches of stories’. In the 1540s Schiavone was clearly important for his younger contemporaries Jacopo Tintoretto and Jacopo Bassano, above all in demonstrating a radically free manipulation of the paint medium to provide a shorthand for form.

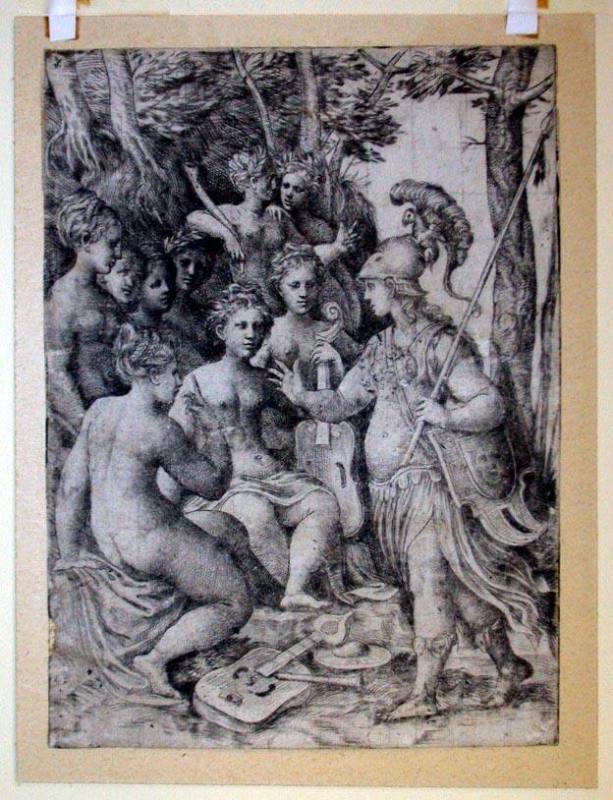

Around 1550, Schiavone, pursuing greater sobriety and control, moderated the turbulence both of his compositions and of his brushwork and increasingly turned to Raphael and Titian for compositional models. Examples of this phase include the Judgement of Midas (Hampton Court, Royal Col.), the Marriage of Cupid and Psyche (New York, Met.), the Holy Family with St Catherine (Vienna, Ksthist. Mus.) and several of Schiavone’s finest and most formal etchings, such as the Holy Family with Saints (b. 63, 64). In the mid-1550s Schiavone enriched this more monumental style with a renewed virtuosity of brushwork, a more finely gauged gamut of paint textures, complex and resonant colour harmonies and (often) a darkening tonality. By these means he effected a fusion of form with a dense atmosphere in a pictorial fabric whose elements tend to lose their separate identities. This development can be seen in such works as his nocturnal Sacra conversazione (British Govt A. Col.), the organ shutters of the Annunciation, St Peter and St Paul (all Belluno, S Pietro) and the Pietà (Dresden, Gemäldegal. Alte Meister). This style reached an apogee in three tondi painted for the ceiling of the sala of Jacopo Sansovino’s Libreria Marciana in Venice: the Force of Arms, The Priesthood and The Empire (final payment 10 February 1556; all in situ), much admired by 16th- and 17th-century writers, and in the altarpiece of Christ and the Disciples on the Way to Emmaus for the Pellegrini Chapel in S Sebastiano, Venice (after 24 June 1557; in situ). Schiavone’s paintings of c. 1552–7 incorporate darkening tonalities, vibrating textures, open brushwork and dematerialized form—features that are, even taken separately, innovative—into vibrant and complex works that in the 16th century were paralleled only (at a somewhat later date) by some of Titian’s late works. Their colouristic and textural richness and forceful chiaroscuro often engender a compelling expressive power. In arriving at this style, Schiavone drew on a close study of Titian and Giorgione.

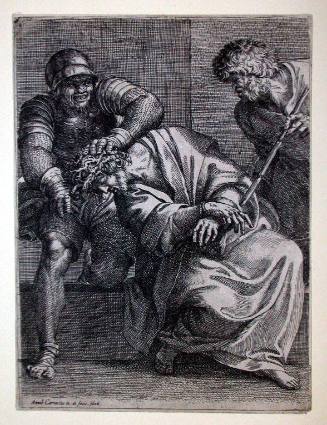

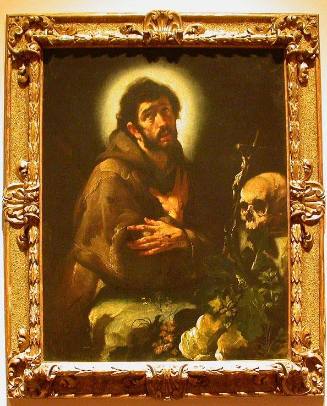

In Schiavone’s final years (c. 1557–63) he received substantial public and professional recognition; his works of this date are notably diverse in character and intention. They include mythological paintings in a light decorative vein, for example two scenes from the Aeneid (both Vienna, Ksthist. Mus.), astonishing in the nonchalant freedom of their handling; two grandiose Philosophers (both c. 1560; Venice, Lib. Marciana), irrationally and perversely majestic; some religious paintings that seem relatively perfunctory; and others of a visionary intensity or tragic depth of feeling unmatched in his oeuvre. Among the latter are an Ecce homo (Padua, Mus. Civ.), two paintings of Christ before Pilate (Hampton Court, Royal Col.; Vienna, Ksthist. Mus.) and the superb large Christ before Herod (Naples, Capodimonte); the last two simultaneously recall Giorgione and prefigure Rembrandt. Two important commissions of this period now survive only in fragments. One was the painted choir-loft of the church of the Carmine, Venice, eulogized by 17th-century writers. A compositional drawing (Vienna, Albertina) and three parapet panels (now organ-loft parapets) survive. The panels show Schiavone’s painterly daring at its farthest reach: all nocturnes, they represent the Annunciation, the Adoration of the Shepherds and the Adoration of the Magi in brushwork of astounding variegation and vitality. A very large painting of a Miracle of St Mark, commissioned by Tommaso Rangone for the Scuola di S Marco some time after 21 June 1562, may never have been completed; a fragment of a Kneeling Woman and Child cut from this canvas is preserved (Vienna, Ksthist. Mus.), though in poor condition; a compositional drawing for the whole also survives (Windsor Castle, Berks, Royal Lib.). After c. 1553, Schiavone produced fewer etchings, but they remained expressively powerful and innovative in their technical freedom, while becoming increasingly extreme in their luminism.

Schiavone’s great historical importance was recognized in the 17th century (Gigli, Boschini) but somewhat lost sight of since. First, in the 1540s he introduced Mannerist modes and motifs into Venetian circles: in this, he was significant especially for the formation of Jacopo Tintoretto and Jacopo Bassano. Even more importantly, he pushed the Venetian painterly mode to an ‘impressionistic’ extreme unprecedented in large-scale paintings of that date, an extreme that implied a revised conception of what a painting is. In etching he was similarly innovative. His technique was unlike that of any contemporary: unsystematically he used dense webs of light, fine, multi-directional hatching to create a tonal continuum embracing form, light, shadow and air. He might enhance that continuum by lightly coating the plate with ink, punctuate it with accents or contrasts in drypoint, or use other unprecedented expedients to enrich his prints’ pictorial dimension. His etchings are the only real equivalent in printmaking of later 16th-century Venetian painterly modes, and his technical experiments were emulated by 17th-century etchers such as Jacques Bellange, Giovanni Benedetto Castiglione and Rembrandt. Schiavone’s mature paintings (c. 1553–63), in which his inventive handling of paint created rich, subtle and complex pictorial fabrics, were influential for Jacopo Bassano, Palma Giovane, El Greco and other lesser artists of the next generation. Still more significantly, they provided precedents for Titian’s late style; and in themselves, they often attain visual beauty and expressive power of a very high order.

Francis L. Richardson. "Schiavone, Andrea." In Grove Art Online. Oxford Art Online, http://www.oxfordartonline.com.proxy.lib.fsu.edu/subscriber/article/grove/art/T076521 (accessed April 11, 2012)

Person TypeIndividual