Image Not Available

for Jacopo da Ponte Bassano

Jacopo da Ponte Bassano

Italian, c. 1510-15 - 1592

Son of (1) Francesco Bassano il vecchio.

1. Training and early paintings, to 1542.

He was apprenticed to his father, with whom he collaborated on the Nativity (1528; Valstagna, Vicenza, parish church). In the first half of the 1530s Jacopo trained in Venice with Bonifazio de’ Pitati, whose influence, with echoes of Titian, is evident in the Flight into Egypt (1534; Bassano del Grappa, Mus. Civ.). He continued to work in the family shop until his father’s death in 1539. His paintings from those years were mainly altarpieces for local churches; many show signs of collaboration. He also worked on public commissions, such as the three canvases on biblical subjects (1535–6; Bassano del Grappa, Mus. Civ.) for the Palazzo Communale, Bassano del Grappa, in which the narrative schemes learnt from Bonifazio are combined with a new naturalism. From 1535 he concentrated on fresco painting, executing, for example, the interior and exterior decoration (1536–7) of S Lucia di Tezze, Vicenza, which demonstrates the maturity of his technique.

Between 1535 and the early 1540s Jacopo often visited Venice, where he saw the late works of Pordenone, whose influence is apparent in works such as the Last Supper (1537), painted for Ambrogio Frizier and rediscovered in the late 20th century in Wormley parish church, Herts, in the altarpiece of the parish church of Borso (Treviso), in the Supper at Emmaus (Cittadella, parish church) and in the same subject (commissioned 1538; Fort Worth, TX, Kimbell A. Mus.), painted for the Podestà of Cittadella, Cosimo da Mosto. Jacopo’s study of Pordenone’s work led him c. 1539 towards Mannerism, as shown in the frescoes on the façade of the dal Corno house, Bassano del Grappa (1539; now Bassano del Grappa, Mus. Civ.), and in the canvas of Samson and the Philistines (c. 1539; Dresden, Gemäldegal. Alte Meister). The limbs and construction of the muscles are defined by drawing, and the cold, enamel-like colours are clearly contained rather than diffuse in the manner of Bonifazio.

In Jacopo’s small altarpiece of St Anne (1541; Bassano del Grappa, Mus. Civ.) the effect of tension, derived from Pordenone, is created by the bodies crowded into a curve in the foreground. The cold, sharp colours and the realistic vigour of the figures clearly show familiarity with Lombard naturalism (in this case that of Giovanni Girolamo Savoldo). In other works painted shortly after St Anne the influences of Moretto and Lorenzo Lotto can also be seen, for example in the Adoration of the Magi (c. 1542; Edinburgh, N.G.), the Virgin and SS Martin and Anthony Abbot (1542–3; Munich, Alte Pin.) and the Flight into Egypt (Pasadena, CA, Norton Simon Mus.). These paintings have an exceptional quality of light and naturalistic vitality; the juxtaposition of dissonant hues gives the colour a constructive force far removed from the Venetian tonality of Bonifazio’s workshop. After 1540 Jacopo lived permanently in the family house at Bassano del Grappa and directed the workshop. In Bassano del Grappa he frescoed the Lion Walking and Marcus Curtius (1541–2) on the façade of the Porta Dieda; these were commissioned by Podestà Bernardo Morosini, whose portrait he also painted (Kassel, Schloss Wilhelmshöhe).

2. Mannerism and the influence of prints, 1543– 1562.

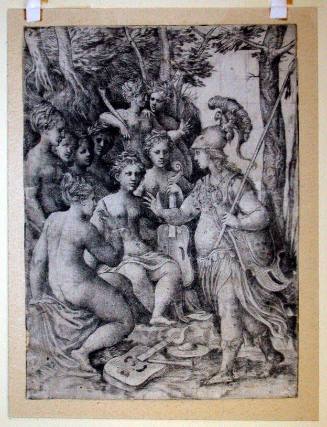

Jacopo kept up with artistic trends by studying a wide range of graphic material, including prints by or after Titian, by Dürer, Giulio and Domenico Campagnola, Agostino Veneziano, Andrea Schiavone, Marcantonio Raimondi and Ugo da Carpi. Typically he alternated between direct observation of nature and reference to graphic prototypes. Like Titian and Jacopo Tintoretto, he followed the Mannerist trend, influenced by the Tuscan painters who came to Venice, notably Francesco Salviati, Giuseppe Porta Salviati and Giorgio Vasari. The Road to Calvary (c. 1543–4; Cambridge, Fitzwilliam) and the Martyrdom of St Catherine (1544; Bassano del Grappa, Mus. Civ. see fig. [not available online]), both inspired by Raphael, mark his move from naturalism to an abstract approach, which reflects Mannerist stimuli.

In the Road to Calvary (c. 1545; London, N.G.) the accentuated elegance of the brushwork and the colour give the first indication of Jacopo’s contact with Parmigianino through the engravings of Andrea Schiavone. An expanded spatiality dominates the Miraculous Draught of Fishes (1545; Washington, DC, N.G.A.), which was inspired by the xylography of the same subject that Ugo da Carpi had taken from Raphael’s cartoon for a tapestry in the Sistine Chapel, Rome. Jacopo referred to these prints in each phase of his development while continuing to give close attention to Venetian artists, from Tintoretto to Paolo Veronese and above all to Titian. Jacopo married Elisabetta Merzari (d 1601) of Bassano del Grappa, in 1546, and they had four sons who became painters. By 1546–7 he had reached an equilibrium between the preciousness of the Mannerist style and a renewed desire for truthful representation. In those years he produced his warmest and most delicate works of that decade: the Adoration of the Shepherds (c. 1546; London, Hampton Court, Royal Col.) and the Rest on the Flight into Egypt (c. 1547; Milan, Ambrosiana). In the latter the landscape and facial types are studied from life, but some details show an extraordinary formal refinement and chromatic exuberance. The iconography of the Holy Trinity (1547; Bassano del Grappa, Santa Trinità) is derived in part from northern European prints but reinterpreted in an original way. In other works produced during this experimental phase Jacopo substantially modified Mannerist suggestions derived from prints. The Last Supper (1546–8; Rome, Gal. Borghese) was inspired by Raphael and by Dürer; the exaggerated figures, agitated drawing and strong shadows reflect Tintoretto. A more prosaic truth is expressed in the painting of Two Hunting Dogs (1548; Paris, Louvre).

After these naturalistic experiments Jacopo returned to the study of Parmigianino through Schiavone in the Virgin in Glory with SS Anthony Abbot and Ludovico of Toulouse (1548–9; Asolo Cathedral). The change is illustrated by the Beheading of St John the Baptist (1550; Copenhagen, Stat. Mus. Kst), with its elegant forms and refined brushwork in short strokes, in the Pentecost (1551; Lusiana, Vicenza, parish church) and in the dramatic Road to Calvary (c. 1552; Budapest, Mus. F.A.), in which elongated figures with sharply drawn faces are crowded in a chiaroscuro setting. In Dives and Lazarus (c. 1554; Cleveland, OH, Mus. A.) the forms derived from Parmigianino and the violent atmosphere assume a naturalistic aspect, which is underlined by such details as the dog in the foreground. Jacopo’s return to the study of Parmigianino in the mid-1550s is apparent in the Adoration of the Magi (c. 1555; Vienna, Ksthist. Mus.), which shows a powerful and imaginative use of colour and light. Its elegant composition and sophisticated figures are also present in other works of the period, such as Susanna and the Elders (c. 1555–6; Ottawa, N.G.). These paintings display a balanced synthesis of light and colour that is lacking in the works from 1557–9; in the Good Samaritan (c. 1557; London, N.G.) light is intensified at the expense of colour, creating vigorous figures that are indebted more to Salviati’s Mannerism than to that of Parma. In the Annunciation to the Shepherds (c. 1558; two versions, Washington, DC, N.G.A.; Rome, Accad. N. S Luca), one of his first explorations of landscape and pastoral, and in St John the Baptist (1558; Bassano del Grappa, Mus. Civ.) the constructive power of light is emphasized by the darkening of the sky.

Towards the end of the 1550s Jacopo received commissions from local clients; in 1558, in addition to St John the Baptist, he painted the frescos in the town hall (untraced except for a small fragment in situ); and c. 1559 he produced a Pentecost (Bassano del Grappa, Mus. Civ.). In the latter his experiments with light during that decade reached a highpoint, and he acknowledged the magical impressionism of Titian in such works as the Martyrdom of St Lawrence (1557; Venice, Gesuiti). Titian’s influence is still evident in St Christopher (c. 1558–9; Havana, Mus. N. B.A.). Shortly after, however, Jacopo’s renewed study of Parmigianino through Schiavone’s engravings brought about a change of direction, as seen in St Paul’s Sermon (1559; Padua, Mus. Civ.), one of the few surviving sketches by the artist, the altarpiece of St Justina and Saints (Enego, S Giustina) and Jacob’s Journey (c. 1560; London, Hampton Court, Royal Col.). Compared with the Adoration of the Magi (c. 1555) in Vienna, these show the revitalizing effect of Jacopo’s recent studies of light: the figures have a more relaxed elegance, and the colours are more transparent.

About 1561 Jacopo received an important commission from Venice, a painting for the church of the Umiltà, SS Peter and Paul (Modena, Gal. & Mus. Estense). Its more classical forms and constructive use of light show the influence of Paolo Veronese, who painted the canvases for the ceiling of the same church. During this brief return to the Venetian tradition, Jacopo painted the Parable of the Sower (c. 1561; Madrid, Mus. Thyssen-Bornemisza), a work demonstrating his renewed interest in pastoral–biblical subjects. The combination of rustic simplicity and elegant stylization also occurs in the Adoration of the Shepherds (c. 1562; Rome, Pal. Corsini).

3. Experimentation and family collaboration, c 1562–81.

The Crucifixion with Saints (1562–3; Treviso, Mus. Civ. Bailo) is a key work, because it indicates the end of Jacopo’s Mannerist studies and a return to a more relaxed classicism. The scene was inspired by Titian but dominated by limpid colour in the style of Veronese. In other works of the period, such as St Jerome (Venice, Accad.) and Tamar Led to the Stake (c. 1563; Vienna, Ksthist. Mus.), there is no trace of Mannerism: colour, no longer the primary means of expression, is subordinated to the unifying power of light. In the altarpiece of the Vision of St Eleuterius (c. 1565; Venice, Accad.) for S Maria Bombardieri in Vicenza, Jacopo produced an inventive synthesis of the pastoral genre and the demands of an altarpiece. New formal interests can be seen in the portrait-like treatment of the faces. Freed from Mannerist preoccupations, Jacopo turned his attention to current developments in Italian painting and continued to paint with a new interest in observation from life and with a Mannerist attention to design.

Jacopo’s new objectivity and well-established formal rigour are also evident in such portrait paintings of c. 1566 as Man with Gloves (London, Hampton Court, Royal Col.) and Torquato Tasso (Kreuzlingen, Heinz Kisters). On returning to biblical themes, Jacopo interpreted them in a pastoral key, with increased use of light. In such works of the period 1565–8 as Jacob’s Journey (c. 1566; ex. Wallraf-Richartz-Mus., Cologne) and its pendant the Meeting of Jacob and Rachel at the Well (c. 1566; Turin, Galleria Antichi Maestri Pittori), the composition is dominated by light, partly due to the minute brushwork, which fragments the form. The effect is completely different from that in the pastoral scenes of the early 1560s, for example in the Parable of the Sower (Madrid, Mus. Thyssen-Bornemisza), where the colour has a certain autonomy and there is a high level of abstraction. Also new in the depictions of biblical history is the use of naturalistic foreground figures and animals without the strained poses of Mannerism.

Jacopo’s search for a new iconography is documented in such drawings as the Reclining Shepherd (Frankfurt am Main, Städel. Kstinst., inv. no. 15216). The small pastoral pictures became popular with Venetian collectors, and to meet the demand Jacopo collaborated with his son (3) Francesco Bassano il giovane. The biblical–pastoral pictures of 1565–70 (e.g. Pastorale, c. 1568; Budapest, Mus. F.A.) may be termed classical, as they are without any inflections from Parmigianino and Salviati. The altarpiece for S Giuseppe, Bassano del Grappa, the Adoration of the Shepherds (1568; Bassano del Grappa, Mus. Civ.), is the culmination of the new pastoral altarpiece, which began with the Vision of St Eleuterius. The forms have an air of classical solemnity, and each minute detail is visible in the crepuscular light.

During the 1570s Jacopo painted large altarpieces for churches in the Veneto and Trentino that show an increased sense of monumentality based on perspective. Often set in twilight, the graduated figures recede diagonally towards the background landscape. Among these works are the Martyrdom of St Lawrence (1571; Belluno Cathedral); the extraordinary St Roch Visiting the Plague Victims (c. 1570–73; Milan, Brera), which synthesized Jacopo’s pictorial experiments, and the Entombment (1574; Padua, S Maria in Vanzo), reflecting Titian’s late works. Evening light also dominates the large biblical compositions of the period, such as the Return of Tobias the Younger, the Israelites Drinking the Miraculous Water (both c. 1573; Dresden, Gemäldegal, Alte Meister) and the Return of Jacob (c. 1573–4; Venice, Doge’s Pal.). An important civic commission is the large lunette with the Rectors of Vicenza before the Virgin (1573; Vicenza, Mus. Civ. A. & Stor.), showing an interest in naturalistic description and the luminous effects that also characterize other paintings, of a small format, of the early 1570s, for example A Greyhound (c. 1571; Turin, priv. col., see Ballarin, 1995, fig.), Portrait of an Old Man (Oslo, N.G.) and Portrait of a Man with Three Books (Rome, Gal. Spada), formerly attributed to Leandro and now in Jacopo’s catalogue (Ballarin, 1995).

St Paul Preaching (1574; Maróstica, S Antonio Abate) is the first large-scale work signed by Jacopo and Francesco, who also assisted in the execution of the series of the Four Seasons (Vienna, Ksthist. Mus.), painted that year. In these small collectors’ pieces the biblical motif, often relegated to the background, was mainly a pretext for portraying seasonal labours in a landscape observed from life. Four scenes from the Story of Noah were also painted in 1574, including the Sacrifice of Noah (Potsdam, Bildergal.); another edition was produced (c. 1577; Krome(r(íž, Archbishop’s Pal.) in collaboration with Francesco. To meet the demand from collectors from c. 1575, Jacopo had many copies of his works made by apprentices and by his sons, Francesco, the relatively untalented Giambattista Bassano (ii) and (4) Leandro Bassano, who showed great ability, especially in portrait painting. One of Jacopo’s few remaining frescoes is the cycle (1575) in the chapel of the Rosary in the parish church of Cartigliano (Vicenza), in which Francesco painted the whole right-hand wall and minor passages elsewhere. For these frescoes Jacopo made preparatory drawings of which a few survive (e.g. Sacrifice of Isaac, charcoal and coloured chalk; Paris, Louvre, inv. no. 2913). Also dating from 1575 is a series of night scenes. Among numerous workshop copies and variants Ballarin (1988) identified a few autograph works by Jacopo, including the Agony in the Garden (two versions, Modena, Gal. & Mus. Estense; Burghley House, Cambs), the Annunciation to the Shepherds (Prague, N. G. Sternberk Pal.) and the Crucifixion on black stone (Barcelona, Mus. B.A. Cataluña). Another masterpiece, the Baptism of St Lucilla (c. 1575; Bassano del Grappa, Mus. Civ.), is characterized by soft lighting and refined colour effects. The same qualities are found in the paintings (c. 1575) in the parish church of Civezzano (Trento), two also signed by Francesco.

Probably in 1576–7 Jacopo invented another type of collectors’ picture: a medium-sized biblical subject in a genre setting (e.g. kitchen or courtyard). Some originals survive, many signed by both Jacopo and Francesco. Such scenes as Supper at Emmaus (Crom Castle, Co. Fermanagh), the Return of the Prodigal Son (Rome, Gal. Doria-Pamphili), Christ in the House of Mary and Martha (Houston, TX, Sarah Campbell Blaffer Found.) and the Mocking of Christ (Florence, Pitti) are known in many versions painted by Jacopo’s sons and followers, who copied them until well into the 17th century. Other works dating from the productive years 1576–7 are the allegories of the Elements (e.g. two, Sarasota, FL, Ringling Mus. A.) and new versions of the Four Seasons (Rome, Gal. Borghese) and of biblical subjects painted during the 1560s, for example the Good Samaritan (Vienna, Ksthist. Mus.). In these compositions, indebted to Giorgione, the figures are immersed in the landscape with no perspectival devices; the forms are not drawn but modelled with colour in a warmer register with dense brushwork.

Among the last works Jacopo executed with Francesco, who moved to Venice in 1578, is the altarpiece, the Circumcision (1577; Bassano del Grappa, Mus. Civ.), signed by both, for Bassano del Grappa Cathedral. This shows a renewed interest in spatial construction: the figures are no longer arranged diagonally but placed in groups balanced by converging and diverging movements. In this and other paintings of the period there is also a new style of figure drawing, as in the small votive altarpiece the Podestà Sante Moro (1576; Bassano del Grappa, Mus. Civ.). Clearly Jacopo was seeking a more expressive way of using light through re-examining his own past and that of Venetian painting from Titian to Tintoretto, as seen, for example, in the Forge of Vulcan (c. 1577; U. Barcelona, on dep. Madrid, Prado), in the portrait of Doge Sebastiano Venier (sketch, oil on copper, 1577; ex-Stuttgart, priv. col., now Bassano del Grappa, Mus. Civ.; see Rearick in Jacopo Bassano, c. 1510–1592, 1992 exh. cat., fig.) and in the portrait of Francesco I de Medici (c. 1578; Kassel, Schloss Wilhelmshöhe) traditionally attributed to Francesco il giovane and now in Jacopo’s catalogue (Ballarin, 1995). Jacopo’s new language developed further in the altarpiece of St Martin (c. 1578–9; Bassano del Grappa, Mus. Civ.), where the scene is not represented naturalistically but evoked through colours saturated with light, and in the altarpiece of the Virgin in Glory with SS Agatha and Apollonia (1580; Bassano del Grappa, Mus. Civ.).

4. The last years, 1582–92.

After Francesco left for Venice, Jacopo collaborated with (4) Leandro. Ballarin (1966; 1966–7) has shown that Jacopo continued to be active in his last ten years. Based on the date of 1585, discovered in Susanna and the Elders (Nîmes, Mus. B.A.), Ballarin compiled a list of these late works, which has been augmented by Rearick (1967) and Pallucchini (1981). In these years Jacopo no longer painted altarpieces but concentrated on smaller religious pictures, especially episodes of the Passion, painted with highly dramatic lighting. Apart from the Susanna, he produced Christ Driving the Money-changers from the Temple (c. 1585; London, N.G.), the Mocking of Christ (c. 1590; Oxford, Christ Church College Pict. Gal.) and the Baptism (New York, priv. col., see Rearick, 1967, fig.). According to Rearick, this last, incomplete work should be identified with the one in the inventory of paintings in the workshop at Jacopo’s death. During the 1580s he used a thick impasto, blurred the forms and handled space expansively; and, loyal to the Venetian tradition, he seemed to be rethinking Mannerism in terms of dramatic and anguished tension.

Jacopo left most of his goods and the ownership of the famous studio to his least talented sons, Giambattista (ii) and (5) Gerolamo Bassano; a smaller share went to (4) Leandro and the bare legal minimum to Francesco il giovane, because, he said, the last two had been trained by him and their works had brought them fame and fortune. All Jacopo’s biographers praised him for his humility. He led a secluded life in the small provincial city where he was born, and he declined invitations to serve foreign princes.

Jacopo maintained close friendships with some of the most important artists of his time, such as Tintoretto, Annibale Carracci and Paolo Veronese. He was an expert musician, and Veronese in the Marriage at Cana (1562–3; Paris, Louvre), paid him a splendid tribute by depicting him playing in an ensemble with Titian, Tintoretto and himself. Jacopo was a keen reader, especially of holy scripture, and had a rigorous moral code, such that he would never paint scenes or figures that might arouse scandal. His interest in botany shows in the realistic flowers and plants in his paintings.

Livia Alberton Vinco da Sesso. "Bassano." In Grove Art Online. Oxford Art Online, http://www.oxfordartonline.com.proxy.lib.fsu.edu/subscriber/article/grove/art/T006767pg2 (accessed March 22, 2012).

Person TypeIndividual

Italian, about 1520 - 1563