Image Not Available

for Jacopo Carrucci da Pontormo

Jacopo Carrucci da Pontormo

Italian, 1494 - 1556/7

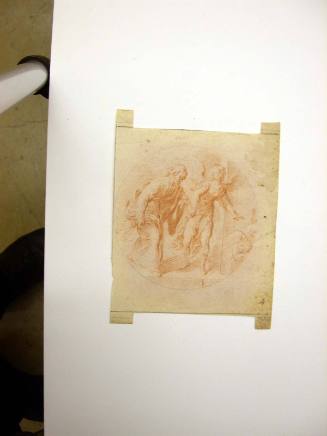

Jacopo da Pontormo: Study of a Man’s Head, red chalk,…Italian painter and draughtsman. He was the leading painter in mid-16th-century Florence and one of the most original and extraordinary of Mannerist artists. His eccentric personality, solitary and slow working habits and capricious attitude towards his patrons are described by Vasari; his own diary, which covers the years 1554–6, further reveals a character with neurotic and secretive aspects. Pontormo enjoyed the protection of the Medici family throughout his career but, unlike Agnolo Bronzino and Giorgio Vasari, did not become court painter. His subjective portrait style did not lend itself to the state portrait. He produced few mythological works and after 1540 devoted himself almost exclusively to religious subjects. His drawings, mainly figure studies in red and black chalk, are among the highest expressions of the great Florentine tradition of draughtsmanship (see fig.); close to 400 survive, forming arguably the most important body of drawings by a Mannerist painter. His highly personal style was much influenced by Michelangelo, though he also drew on northern art, primarily the prints of Albrecht Dürer.

1. Life and works.

(i) Formative years: Classicism to Mannerism, before 1520.

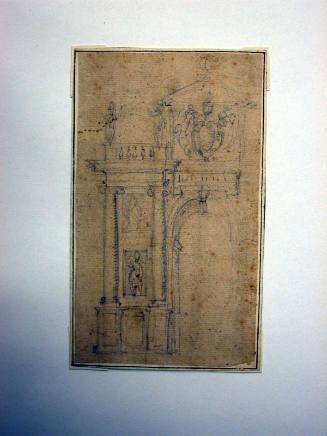

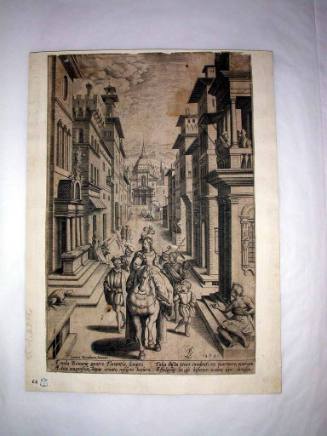

Pontormo probably studied with Leonardo da Vinci in 1508 (Vasari), then with Piero di Cosimo, and by 1510 with Mariotto Albertinelli. Around 1512 he was an assistant of Andrea del Sarto and painted his earliest surviving work, St Catherine of Alexandria (1512; Florence, Uffizi; see Proto Pisani). In his first independent paintings, all frescoes (now detached), he followed the High Renaissance classical style of Fra Bartolommeo and del Sarto. These include a Faith and Charity (1513–14; Florence, Gallerie), originally surrounding the arms of Pope Leo X over the portico of SS Annunziata, Florence, the Hospital of St Matteo (c. 1514; Florence, Accad.) and the Virgin and Child with Saints (c. 1514; Florence, SS Annunziata) for S Ruffillo. Two further frescoes demonstrate a fully developed High Renaissance style: the lunette fresco of St Veronica (with the vault frescoes of God the Father, Putti with the Instruments of the Passion and Putti with the Arms of Leo X; all Florence, S Maria Novella), which was executed to honour the Medici pope’s visit to Florence in 1515 and marked Pontormo’s début in the service of the Medici family; and the Visitation, part of the cycle of the Life of the Virgin (1514–16; Florence, SS Annunziata). The latter is notable for its dramatic rhetoric and classical amplitude of form. Among his earliest works on panel were three (1515–17; London, N.G.) of a series of scenes from the Story of Joseph, painted for the bridal chamber of Pierfrancesco Borgherini. His Portrait of a Jeweller (c. 1518; Paris, Louvre) and Portrait of a Musician (c. 1515–16; Florence, Uffizi), were similarly based on del Sarto’s classical style. Cosimo de’ Medici il Vecchio (1519; Florence, Uffizi) is an emblematic profile image commemorating the founder of Medici power in Florence and allegorizing the family’s political ambitions.

Around 1517 Pontormo broke with the classicism of his teachers and of his own early paintings and started creating radically experimental works in the new Mannerist style. This change is most clearly apparent in his major early work, the Visdomini Altarpiece, which depicts the Virgin and Child with Saints (1518; Florence, S Michele Visdomini). The design is based on the sacra conversazione composition as formulated by Fra Bartolommeo, but its classical stability and harmony are undermined by a nervously complex fragmentation of form, an intense projection of emotional states and an implausible spatial construction. Another experimental work is the last of the Borgherini panels, Joseph in Egypt (c. 1518; London, N.G.), in which his treatment of space and light is irrational and complex, the background Germanic and the figure types and draperies increasingly individual. According to Vasari, the small boy dressed in contemporary style in the foreground is Bronzino.

(ii) Mature works, 1520–30.

During the 1520s a further series of experimental works established Pontormo’s mature style. The first was the lunette fresco of Vertumnus and Pomona painted in the Gran Salone of the Medici villa at Poggio a Caiano (1520–21; in situ) as part of a collaborative project (never completed) with del Sarto and Franciabigio. Vertumnus, the Roman god of harvests, and Pomona, the goddess of fruit trees, are shown with other gods in an idyllic pastoral scene on a sunlit wall. The design is novel and depends on subtle, abstract relationships of shape and colour, combined with precisely described realistic details that are quite contrary to classical notions of idealization. The preparatory drawings (Florence, Uffizi) show that Pontormo moved away from first ideas for rhythmically interrelated, Michelangelesque nudes towards the delicate patterns and bucolic mood of the final version. The individual figure studies for Vertumnus and for the goddess on the wall are among those that possess a striking psychological intensity and reveal his interest in experimental, angular shapes.

In the fresco series of the Passion (1523–6; Florence, Certosa del Galluzzo, Pin.) and a Supper at Emmaus for the same monastery (1525; Florence, Uffizi), Pontormo drew inspiration from the prints of Dürer, whose Late Gothic art suggested the power of a more abstract, spiritual style. This influence, the psychological intimacy of the figures and Pontormo’s characteristic pale tonalities give these pictures an emphatically unclassical character. Many figures and poses are adapted from Dürer’s Small Passion series, as for example in the Agony in the Garden, which takes figures from Dürer’s woodcut of that subject. The graphic style, too, is borrowed from the woodcuts, as in the broken line and angular draperies of the study of St John (Florence, Uffizi) for the Agony in the Garden.

Jacopo da Pontormo: Lamentation, oil on panel, 3.13×1.92 m, 1525–8…In the mid-1520s Pontormo’s renewed contact with Michelangelo resulted in a reaccommodation of his art to the classical notion of harmony. In 1525–8 he painted the most important ensemble of his maturity, the decoration of the Capponi Chapel in S Felìcita, Florence (in situ). The altarpiece shows the Lamentation; in the pendentives of the dome are tondi of St John the Evangelist, St Matthew, St Luke, and St Mark, and on the side wall is a fresco of the Annunciation. In the Lamentation, generally acknowledged to be his masterpiece, Pontormo combined a new sense of ornamental beauty, polished surfaces and exquisitely refined line with the insubstantial, floating forms, the spatial irrationality and the poignant communication of feeling that are hallmarks of his Mannerism. The colours—high-keyed, clear blues, acid greens and pinks, with little light and shade—intensify the picture’s strange and haunting grace. The drawings for the Lamentation, such as the sculptural, precisely modelled study for the Dead Christ (Florence, Uffizi), are mainly in red chalk and are characterized by a new feeling for the beauty of line and light.

Most of Pontormo’s paintings of the late 1520s, such as the Visitation (Carmignano, S Michele), are in a similar style to that of his work at the Capponi Chapel, though there are also some, such as the monumental altarpiece depicting the Virgin and Child with St Anne and other Saints (c. 1529; Paris, Louvre), in a more delicate manner. In the portraits of these years Pontormo broke with his early style, based on the portraits of del Sarto, to create the typical Florentine Mannerist image, with its lengthened format and strict frontality; the Portrait of a Young Man in a Pink Satin Cloak (c. 1509–30; Lucca, Villa Guinigi), which is thought to depict Alessandro de’ Medici but more likely represented Amerigo Antinori (Costamagna), and Maria Salviati and Cosimo de’ Medici (c. 1527/?1537; Baltimore, MD, Walters A.G.) are of this type. The Portrait of Two Friends (c. 1523–4; Venice, Col. Cini) is a penetrating study of the relationship between the two male sitters.

(iii) Late works, 1530–56.

The Legend of the Ten Thousand Martyrs (c. 1529–30; Florence, Pitti), in which Pontormo experimented with complex male nude poses, both concludes the development of the 1520s and looks forward to the increasing influence of Michelangelo. This influence is evident in the ornamental works that have an affinity with, but are distinct from, those of his Mannerist contemporaries Agnolo Bronzino, Francesco Salviati and Vasari. In the early 1530s Pontormo executed two paintings from cartoons by Michelangelo: the Noli me tangere (1531–2; ex-Milan, priv. col., see Berti, fig.) and Venus and Cupid (1532–4; Florence, Accad. B.A. Liceo A.). He painted fresco decorations (destr.) in the loggias of the Medici villas at Careggi (1535–6) and Castello (1537–43), for which preparatory drawings survive (Florence, Uffizi; see also Cox-Rearick, 1964), and in 1545 contributed to another decorative project for the Medici: the tapestries of the Story of Joseph. These were largely by Bronzino, but Pontormo designed the Lament of Jacob, Joseph Capturing Benjamin (both Rome, Pal. Quirinale) and the Temptation of Joseph (Florence, Pal. Vecchio).

In 1546 Pontormo was one of the artists who wrote to Benedetto Varchi in response to his request to enter the Paragone (debate) on the primacy of painting or sculpture; these letters, defending Florentine disegno, were published in Varchi’s Due lezioni (1549). Around this time Pontormo began work on his frescoes, mainly of Old Testament subjects but also including a Resurrection and Last Judgement (1546–56, destr. 1742), in the choir of S Lorenzo, Florence. Painted for Cosimo I de’ Medici, they were the major work of his last years and were completed by Bronzino after Pontormo’s death. The preparatory black chalk drawings (mainly Florence, Uffizi) are the only testimony to Pontormo’s late style: that for Christ in Glory (Florence, Uffizi) fuses the influence of Michelangelo with a most eccentric personal grace.

The elongation and spirituality of Pontormo’s late portraits, such as the sombre Alessandro de’ Medici (1534; Philadelphia, PA, Mus. A.) and Giovanni della Casa (1540–44; Washington, DC, N.G.A.), coincide with the rarefied atmosphere of these late religious works. The Portrait of a Halberdier (?1530–7; Los Angeles, CA, Getty Mus.) probably depicts Cosimo I de’ Medici (Keutner; Forster; Cox-Rearick; Costamagna) but is also thought to represent Francesco Guardi Berti. Pontormo’s portraits differ from those of his contemporaries in their subtle and complex psychological communication.

2. Influence and posthumous reputation.

Pontormo’s major follower was Bronzino, his pupil in the 1520s, who transformed his master’s early Mannerism into the mid-century maniera. Also influenced by Pontormo were Pier Francesco Foschi, Jacone and, later, Giovan Battista Naldini, Pontormo’s pupil between 1549 and 1556. After Pontormo’s death, his reputation declined with the advent of late Mannerism, although in the 1570s some Florentine artists, including Maso da San Friano, Mirabello Cavalleri (1510/20–72) and Girolamo Macchietti, tried to free themselves from the formulae of this style by imitating aspects of his work. But the Counter-Reformation demand for realism in religious art soon eclipsed his influence. None of his paintings was engraved; even his portraits were not admired. The destruction in 1738 of his fresco cycle in S Lorenzo was symptomatic of the low repute of his work. His reputation was not restored until the 20th century, with the publication of Clapp’s monographs on his drawings (1914) and paintings (1916); an exhibition marking the 400th anniversary of his death (1956) initiated further specialized studies (e.g. Berti, Cox-Rearick, Forster), and the celebration of the 500th anniversary of his birth initiated a cluster of further publications in 1993–4.

Janet Cox-Rearick. "Pontormo, Jacopo da." In Grove Art Online. Oxford Art Online, http://www.oxfordartonline.com.proxy.lib.fsu.edu/subscriber/article/grove/art/T068662 (accessed April 11, 2012).

Person TypeIndividual

Italian, c. 1510 - 1561