Bernardo Buontalenti

Italian, 1531 - 1608

Italian architect, engineer, designer, painter and inventor. He was one of the great Renaissance polymaths and was not only admired but also liked by his contemporaries. A friend of princes, he spent most of his life at the Tuscan court, but his influence stretched throughout Europe.

1. Training and early work, before 1570.

After his parents were drowned, he was brought up at the court of Cosimo I de’ Medici. As an apprentice he trained first with Francesco Salviati, then with Agnolo Bronzino, Giorgio Vasari and finally Don Giulio Clovio. His education must have been broadly based, as he was appointed tutor at the age of 15 to the future Francesco I de’ Medici, to whom he taught not only drawing, colouring and perspective but also architecture and engineering. This was the beginning of a lifelong friendship, in which they shared a passionate interest in the natural sciences.

Buontalenti’s earliest known work was a wooden crucifix (destr.) for the church of S Maria degli Angeli, Florence. On 1 February 1550 a document refers to his work as a pyrotechnist, from which he earned his nickname. In 1556 he was sent as a specialist adviser in engineering to Fernando Alvárez de Toledo, Duke of Alba, for whom he designed fortifications at Civetta del Trono. He also built the much-feared Florentine cannon nicknamed ‘Scacciadiavoli’ (destr.). In 1562–3, with Francesco de’ Medici, he visited Madrid, where both men admired the oriental porcelain collection of Philip II of Spain. Buontalenti is credited with the creation of two soft-porcelain pieces (c. 1565) in Florence. He is also recorded as working in Madrid as a miniaturist, executing a number of portraits and paintings of the Virgin for the King.

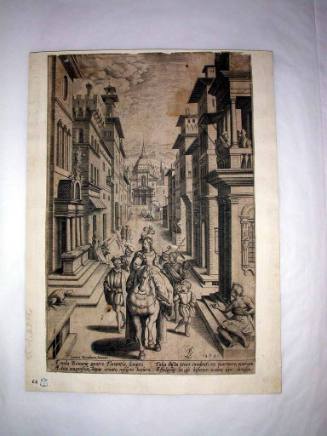

Buontalenti’s first recorded secular architectural work (1567) was the house for Bianca Capello, mistress and later wife of Francesco de’ Medici. This was followed in 1569 by the commission for the villa and gardens at Pratolino, just outside Florence (now mostly destr.), to which a visit was almost obligatory for visitors to Tuscany. As a result, Pratolino had a major influence on European garden design and was studied through contemporary descriptions and engravings. The villa had evolved from ideas current at the time and discussed at the Medici court, and it epitomized Mannerist art. The villa’s design was novel, anticipating Buontalenti’s numerous experiments with the form over the following 20 years. The internal courtyard was omitted, the north and south façades were treated differently, and the central portion was raised considerably higher than the flanking wings. The vertical axis was emphasized by the two formal terraces leading down to the long avenue surrounded by the wild garden.

The letters of Benedetto Uguccioni (Florence, Archv Stat.), who supervised the building works, give an insight into Buontalenti’s working methods. Work began on the villa before he had decided on the form of the main entrance, and this seems to have been a typical practice in later works. Two drawings for the doorway survive in the Uffizi, Florence. The garden was a combination of formal walks, punctuated with pools, grottoes and fountains, and wild groves dotted with architectural caprices. Here Buontalenti’s skill as an engineer was particularly useful in transporting over five miles the huge amount of water needed to service the fountains. The six main grottoes were on two levels beneath the terraces by the house. The most admired was the Grotto of Galatea, with Galatea appearing on a golden shell pulled by dolphins, preceded by a Triton rising from the rocks blowing a trumpet.

2. Architectural work, after 1570.

Buontalenti’s ability as an engineer continued to shape his career. During the 1570s he is recorded as working on the fortifications at various cities including Pisa, Siena, Prato (c. 1574) and Livorno (1576), where he was responsible for the design of the harbour that helped make Livorno the second most important port in the Mediterranean by the end of the 16th century. He also constructed the canal (1573) between Livorno and Pisa.

Buontalenti’s next major architectural commission was the Casino de’ Medici (1574; now the Palazzo delle Corte d’Appello), again for Francesco de’ Medici. It was built as a garden house opening on to an orchard, on the outskirts of Florence. The window arrangement is typical of Buontalenti’s work, especially the elaborate detailing, where consoles flank carved shells and drapery swags beneath the ground-floor windows. However, the overall effect is of simplicity and harmony. His capricious spirit is evident in another work begun in 1574, the chancel of Santa Trìnita (which has since been transferred to S Stefano). Here the steps of the chancel fan outwards like heavy folds of drapery from a pleat, contrasting with a very precise balustrade above.

On the death of Vasari in 1574, Buontalenti became chief architect to the Tuscan court. In this capacity he oversaw the conversion of the top floors of the Uffizi into the grand ducal art gallery. Around 1580 he designed the Tribuna in the Uffizi for the display of Francesco de’ Medici’s greatest art treasures. The room is octagonal with a diffused light issuing from windows in the drum, which in turn is reflected by the mother-of-pearl inlaid into the vault. He also completed the great grotto in the Boboli Gardens, Florence, adding the elaborate upper storey, which incorporated natural rock formations and foliage framing the Medici coat of arms. The interior of the grotto housed Michelangelo’s four Slaves (Florence, Accademia), which had recently been acquired by the Medici. They were set in the corners of the interior space amid roughly carved rocks, natural rock formations such as stalactites and frescoes of fantastic alpine landscapes by Bernardino Poccetti.

Buontalenti’s major architectural works of the 1580s and 1590s include villas at Le Marignolle (1587), Castello (1592) and Artimino (1597), where in keeping with his working method at Pratolino he did not design the doors, chimney and fireplace until the first floor was complete. Like other Florentine villas of the time, these buildings were less grandiose and massive and had a neater, more controlled appearance than similar buildings in Rome, with smooth light surfaces ornamented with sparing dark patterns. Buontalenti’s villas, however, have a stronger sense of volume than the typical Florentine villa. They are articulated more strongly using towers and loggias, and the windows are more definite elements in the patterning of wall surfaces. Buontalenti introduced more detail and a more inventive manner, as in the fantastic array of chimneys at the Villa Artimino, Signa. There is visual movement—often no more than the arrangement of windows, but this gives an air of vitality and lightness balancing the almost fortress-like architectural elements—yet there is a strong overall sense of balance and order. Towards the end of his life, Buontalenti had two architectural failures: the façade of the cathedral and the Cappella dei Principi at the church of S Lorenzo, Florence. His proposed designs (Florence, Uffizi) were too inventive, and as a result of the consequent incoherence they remained unexecuted.

3. Other activities.

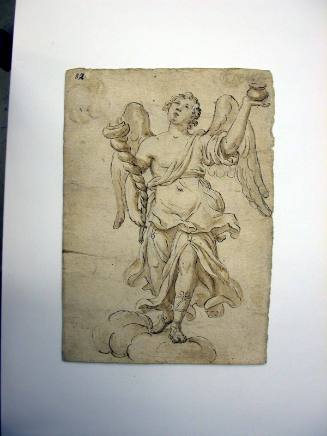

In addition to his architectural achievements, Buontalenti excelled as a theatrical designer. His career in this area began with a period as assistant to Vasari; he is first mentioned in connection with the celebrations for the visit (1569) of Grand Duke Charles of Austria, when he was responsible for costumes transforming peasants into frogs. His skill as a designer was also required at state ceremonies such as baptisms and funerals, which in their lavishness attempted to bolster Medici claims as the rulers of Tuscany and as European powers. For the obsequies of Grand Duke Cosimo de’ Medici, Buontalenti designed a stepped baldacchino laden with 3000 candles, for which the immediate precedent was the funeral of Emperor Charles V in 1558. However, such designs can be traced back to the funeral pyres of the Roman Empire, mentioned in Tommaso Porcecchi’s treatise Funerali antiche di diversi popoli et natione (1574). Other elaborate settings were executed with just as much pomp and display, for example for such celebrations as the baptism of Filippo de’ Medici in 1577. On that occasion the medieval interior of the Baptistery in Florence was ripped out and replaced by an elaborate double ramping staircase (destr.) leading to the tribune, where a new font and a platform of pietra dura for the child were placed. For the same celebrations he designed a number of firework-breathing monsters.

In 1586 Buontalenti built the Teatro Mediceo (capacity 3000) on the top floor of the Uffizi. The inaugural performance was during the wedding festivities for Virginia de’ Medici and Cesare d’Este, Duke of Modena. Contemporary accounts mention that he used bold colours for costumes and that he experimented with lighting, producing a more united and convincing effect than had previously been achieved. The audience was enthusiastic about the perspective view of Rome, which Buontalenti painted on a range of stage flats and backcloths, and which were viewed through a proscenium arch. In 1589, for the month-long celebration of the marriage of the Grand Duke Ferdinand I de’ Medici to Christina of Lorraine, Buontalenti designed a series of intermezzi on fantastic, mythological and cosmological themes, in which music, dance and scenic effects were combined. For his Great Naval Battle, another part of the same celebration, the entertainment began with an elaborate tournament in the courtyard of the Palazzo Pitti; when the guests returned from dinner they found the courtyard flooded and 18 galleons ready for a mock battle. The records for Il rapimento di Cefalo in 1600 describe it as having the most marvellous machines that had ever been seen and compared it to the spectacles of ancient Rome: Buontalenti apparently produced mountains that rose from the earth, flying Cupids, gods on clouds and elaborate sea scenes with leaping fish and whales.

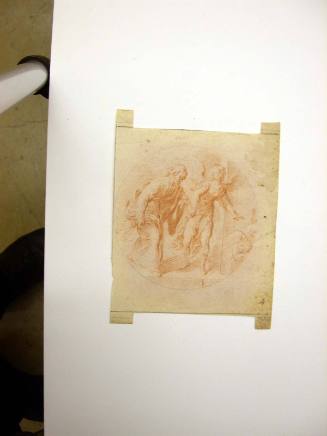

Few of Buontalenti’s paintings survive, although there is a Self-portrait (Florence, Pitti) and a miniature of the Holy Family (Florence, Uffizi). He was also known for his skill with gemstones, and a lapis lazuli vase designed by him is in the Palazzo Pitti, Florence.

Alice Dugdale. "Buontalenti, Bernardo." In Grove Art Online. Oxford Art Online, http://www.oxfordartonline.com.proxy.lib.fsu.edu/subscriber/article/grove/art/T012313 (accessed March 22, 2012).

Person TypeIndividual

Flemish, 1575 - 1632