Image Not Available

for Amadeo Modigliani

Amadeo Modigliani

Italian, 1884 - 1920

Italian painter, draughtsman and sculptor. While he is acknowledged to be one of the major artists of his generation, he was not as experimental and daring as his contemporaries. The direction of Picasso’s work, for instance, changed radically between 1906 and 1909 as a result of the influence of Cézanne and other styles of art (notably African), but Modigliani’s assimilation of these sources had no such far-reaching consequences. Given Modigliani’s limited subject-matter in painting and sculpture, he achieved an extraordinary range of psychological interpretations of the human face, maintaining his individuality through his distinctive elongations of face or form.

1. Training and early work, to 1909.

Modigliani was the youngest of four children of Flaminio Modigliani and Eugenia Garsin, who were both of Jewish descent. Never physically very strong, Modigliani was severely ill three times during his youth. In 1897, when he was 13, his mother wrote that he already saw himself as a painter. On 1 August 1898 he began to study in Livorno with the painter Guglielmo Micheli (1886–1926), a late representative of the Macchiaioli school of Italian plein-air painting.

Modigliani’s studies in Livorno were often interrupted by illness. In late 1900 or early 1901 he contracted pleurisy, which left him with a tubercular lung. When his health improved, he toured Italy with his mother. His visits to Naples, Capri, Amalfi, Rome, Florence and Venice exposed him to many of Italy’s most important works of art. During his travels Modigliani corresponded with his friend Oscar Ghiglia; the five surviving letters (see Mann, pp. 19–22) provide a rare and invaluable first-hand account of the young artists’ idealism and aspirations. In May 1902 he enrolled at the Accademia di Belle Arti in Florence. The following year he moved to Venice, where he continued his academic studies for three more years. The only surviving work from this period is the pastel portrait of Fabio Mauroner (c. 1905; Milan, Gal. Naviglio).

In January 1906 Modigliani arrived in Paris, where, during the next few years, he absorbed a number of influences as he experimented and struggled to find a personal style. He settled in Montmartre, where he joined in artists’ gatherings at Le Bateau-Lavoir and other studios, and enrolled at the Académie Colarossi. In autumn 1907 he met Dr Paul Alexandre, who became his first patron and a close friend until 1914. During this time the young doctor acquired about 25 paintings and numerous drawings.

The watercolour Head of a Woman Wearing a Hat (1907; Boston, MA, William Young, see Hall, pl. 6), with its linear outlines and flat planes of colour, is clearly related to the work of Toulouse-Lautrec. Modigliani also admired Fauvism and Picasso’s Blue Period canvases. The tonality and subject-matter of Head of Girl (1908) is closely related to Picasso’s Blue Period portraits, as is The Jewess (1908; priv. col., see Mann, p. 47), exhibited in Paris at the Salon des Indépendants (1908) along with four other paintings and a drawing. However, he seemed somewhat in awe, if not a little jealous, of Picasso’s prodigious talent. The elegant pose of the model in The Horsewoman (1909; Mr and Mrs Alexander Lewyt priv. col., see Hall, pl. 7) superficially resembles the fashionable society portraits of Giovanni Boldini and Sargent, in which he was also interested, but it lacks the slick bravura of their brushwork.

Cézanne’s late portraits were the single most important influence on Modigliani’s development. In Portrait of Pedro (1909; priv. col., see Hall, pl. 1) the deep-blue background, the blue-black colour of the jacket and the rich earth colours of the face are a paraphrase of Cézanne’s modelling: structure and volume are defined by the accretion of tightly knit sequences of colour patches. After 1909 Modigliani’s work ceased to reflect so blatantly that of another artist.

2. Sculpture, 1909–14.

As early as 1902 Modigliani had produced his first three-dimensional work (untraced) at Pietrasanta, near Carrara, and thereafter declared to friends and family that he was a sculptor. Some time during the first six months of 1909 he moved to a new studio in Montparnasse, 14 Cité Falquière. Dr Alexandre introduced him to Constantin Brancusi, a meeting that stimulated Modigliani’s sculptural ambitions. Brancusi’s early stone carvings, such as the Head of a Girl (1907; untraced, see F. Back: Constantin Brancusi: Metamorphosen plastischer Form, Cologne, 1987), with its smooth face, elongated nose and small mouth, certainly influenced the style of Modigliani’s series of thin stone heads executed between 1909 and 1914 (e.g. c. 1911; New York, Guggenheim). But even more important was the moral example of Brancusi, who retained his individuality and remained fiercely independent of current movements of the avant-garde in Paris. Modigliani, dedicated to working directly in stone, followed Brancusi’s dictum, ‘Direct carving is the true path towards sculpture’.

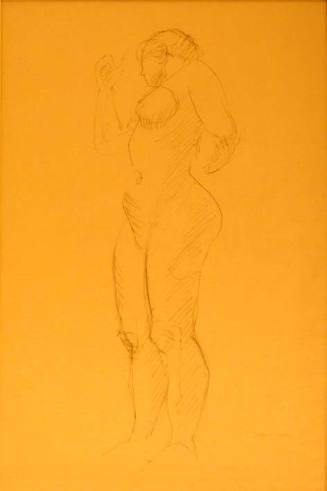

Owing to ill-health Modigliani produced relatively few sculptures, one of the greatest disappointments of his life. His early sculptures in wood (1907–8) are untraced. From 1909 he produced carvings in stone, of which there are 25 examples generally accepted to be by him: 23 heads, a standing figure (1912; priv. col., see Mann, p. 75) and a caryatid (c. 1913; New York, MOMA). While it is impossible to establish an accurate chronology of these works, it is generally agreed that Modigliani concentrated on sculpture and related drawings between 1909 and 1914. It was during this period that he began subtly to assimilate non-European sculptural traditions, African art being the most influential.

Modigliani had met Picasso before 1909 and must have been aware of his interest in African, Greek, Khmer and Egyptian art; he may have seen works in Picasso’s collection. Modigliani’s friendship with Jacques Lipchitz and Brancusi was another link with African art. His thin, elongated stone heads, such as The Head (c. 1911; London, Tate), have usually been associated with Baule masks from the Ivory Coast. Other styles may also have been sources of inspiration, for example the masks of the Fang and Yaure peoples (of Gabon and the Ivory Coast respectively). Other sources have also been suggested, including Archaic Greek kore and Khmer and Egyptian sculpture. But just as Modigliani in his paintings consciously maintained his independence from the work of Picasso and the avant-garde, so in his sculpture he was careful not to fall prey to mere imitation.

The stone heads were conceived as a series, as was his unexecuted group of caryatids. Seven were exhibited at the Salon d’Automne (1912) as Têtes, ensemble décoratif. Lipchitz saw some of the sculptures arranged ‘like tubes of an organ, to produce the special music he wanted’. Epstein recalled that at night Modigliani ‘would place candles on the top of each one and the effect was that of a primitive temple’.

Both as painter and as sculptor Modigliani concentrated on making portraits. Though he abandoned sculpture in late 1913 or early 1914 to return to painting, the years he had devoted to sculpture influenced the style of his portraits of 1914–20. The most striking example is Lola de Valence (1915; New York, Adelaide Milton de Groot priv. col.), which is more a re-creation in two dimensions of his stone heads than it is a representative portrait.

3. Final years, 1914–20.

In 1914 Modigliani met Paul Guillaume, who became his dealer for the next two years, and he began a stormy two-year relationship with Beatrice Hastings, the subject of several portraits (e.g. 1915; Toronto, A.G. Ont.), most of them lifeless. Between 1914 and 1916 he executed studies of his lovers, friends and colleagues, which are among the finest portraits in early 20th-century art. His work was intensely autobiographical by comparison with most painters of his generation and provides the most striking evidence of his numerous contacts with the artistic and literary avant-garde in Paris. His subjects included Diego Rivera (1914; priv. col., see Hall, pl. 16), Pablo Picasso (1915; New York, Perls Galleries), Juan Gris (1915; New York, Met.), Jacques Lipchitz (1916; Chicago, IL, A. Inst.), Henri Laurens (1915; priv. col., see Mann, p. 100), Moïse Kisling (pencil, 1915; priv. col., see Mann, p. 102), Max Jacob (1916; Düsseldorf, Kstsamml. Nordrhein-Westfalen), Jean Cocteau (1916; New York, Pearlman Found. Inc., see Hall, pl. 22), Paul Guillaume (1916; Milan, Gal. A. Mod.) and Leopold Zborowski (1918; priv. col., see Hall, pl. 35). In contrast to the tentative, experimental manner of the pre-war paintings, Modigliani’s uniquely personal style and vision attain maturity in these works.

The painter Chaïm Soutine was the subject of one of Modigliani’s most penetrating character studies of the period, Chaïm Soutine Seated at a Table (c. 1916–17; Washington, DC, N.G.A.). While some of his portraits are either impersonal—the eyes are often left blank—or almost caricatures of the sitter, this painting is a devastatingly honest, penetrating interpretation of the subject’s psychological state of mind. Apart from the characteristically long neck, Modigliani avoided the highly stylized facial features found in many of his portraits, which tend to distance the viewer from the model. This is one of the most naturalistic of all Modigliani’s portraits. The eyes, one slightly higher than the other, brilliantly portray Soutine’s sense of despair and hopelessness, attitudes with which Modigliani could readily identify.

In 1916 Leopold Zborowski became Modigliani’s dealer and began to support him with regular payments. The following year Modigliani met Jeanne Hébuterne, with whom he lived until his death (their daughter, Jeanne Modigliani, was born in 1919). His many portraits and half-length studies of her (e.g. 1918; priv. col., see Mann, p. 170) define his late, highly mannered style, in which the elongation of the neck is increasingly exaggerated. In the best of these portraits Modigliani sympathetically captures the warmth and affection of his lover.

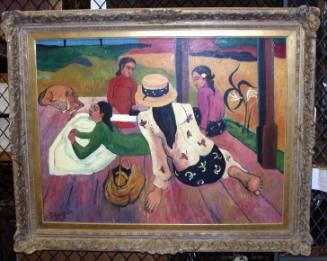

In December 1917 Modigliani exhibited his great series of reclining nudes at the Galerie Berthe Weill, Paris; the exhibition was closed by the police on the grounds of obscenity. Yet these works continue the great tradition of the nude exemplified in the work of Giorgione, Titian, Goya and Manet. For example, the pose of Reclining Nude with Blue Cushion (1917; Milan, G. Mattioli priv. col.) appears to have been directly inspired by Giorgione’s Sleeping Venus (Dresden, Gemäldegal. Alte Meister). The eroticism and unabashed sensuality of Modigliani’s nudes are heightened by the models’ portrayal as individual women (see fig.). Their expressions seem inviting, yet there is a sense of intrusion into their private world. In 1918, when Modigliani’s health began to deteriorate, he went with Jeanne to the south of France. Somewhat recovered, he returned to Paris the following year. His last works include portraits of his friend Lunia Czechowska (1919; priv. col., see Mann, p. 189), of Jeanne Hébuterne (1919; priv. col., see Mann, p. 201) and a Self-portrait (1919; priv. col., see Mann, p. 197). Modigliani died of tubercular meningitis, aggravated by drugs and alcohol, in a Paris hospital, and he was buried at Père-Lachaise cemetery.

Alan G. Wilkinson. "Modigliani, Amedeo." In Grove Art Online. Oxford Art Online, http://www.oxfordartonline.com.proxy.lib.fsu.edu/subscriber/article/grove/art/T058805 (accessed April 11, 2012).

Person TypeIndividual

Italian, 1883 - 1966