Image Not Available

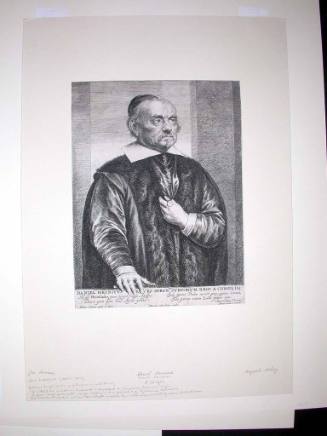

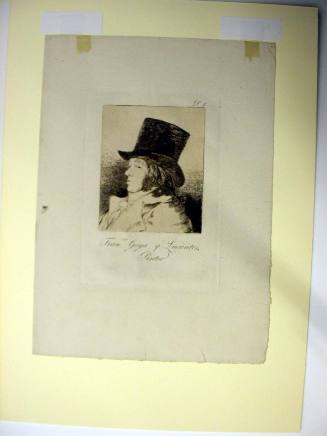

for Sir Peter Lely

Sir Peter Lely

British, 1618 - 1680

Dutch painter, draughtsman and collector, active in England. By a combination of ability and good fortune, he rapidly established himself in mid-17th-century London as the natural successor in portrait painting to Anthony van Dyck. Between van Dyck’s death in 1641 and the emergence of William Hogarth in the 1730s, Lely and his successor, Godfrey Kneller, were the leading portrait painters in England. After the restoration of the monarchy in 1660, Lely dominated the artistic scene, and his evocation of the court of Charles II is as potent and enduring as was van Dyck’s of the halcyon days before the English Civil War. Although Lely’s reputation was seriously damaged by portraits that came from his studio under his name but without much of his participation, his development of an efficient studio practice is of great importance in the history of British portrait painting. The collection of pictures, drawings, prints and sculpture he assembled was among the finest in 17th-century England after the dispersal of the legendary royal collections.

1. Life and work.

(i) Training in Holland and early years in England, before c. 1656.

At the time of Lely’s birth, his father, Johan van der Faes, was captain of an infantry company in a Dutch regiment serving the Elector of Brandenburg. His mother, Abigail van Vliet, came of a distinguished Utrecht family. The van der Faes family, perhaps originally from Antwerp, were people of substance in The Hague, where they had, since 1562, owned a house called in de Lelye because of the lily carved on its gable. From an early age Peter assumed the name of the house, a nickname by which he was always known. In 1637 he appeared as Pieter Lely in a list, in the minutes of the Guild of St Luke in Haarlem, of the pupils of Frans Pietersz. de Grebber (1573–1649).

Within ten years Lely had gone to London. There is no documentary evidence that he arrived there before van Dyck’s death, and in stark contrast to the circumstances in which van Dyck had flourished, Lely built up his reputation and practice in a country torn by civil war and in a capital abandoned by the court. He was made freeman of the Painter-Stainers Company in London on 26 October 1647. By June 1650 he was established in a house on the Piazza in Covent Garden, a fashionable quarter where he lived for the rest of his life.

In the earliest printed account of Lely’s career, published by Richard Graham in 1695, it is stated that when he arrived in England, he ‘pursu’d the natural bent of his Genius in Lantschapes with small Figures, and Historical Compositions: but finding the practice of Painting after the Life generally more encourag’d, he apply’d himself to Portraits’. A small number of landscapes with figure subjects survive from the earliest period in Lely’s career. Two small, very early canvases in the manner of Cornelis van Poelenburgh, Diana and her Nymphs Bathing (Nantes, Mus. B.-A.) and the Finding of Moses (Rennes, Mus. B.-A. & Archéol.), may have been painted before Lely left Holland. For all their obvious weaknesses, they already show a touch of poetry, a nostalgic mood in the landscape, an original richness of colour and an individual handling of light. In the colour in particular, and perhaps in the mood, there are reminiscences of the neo-Venetian qualities that painters such as Frans Wouters had evolved, partly from studying van Dyck. The poet Richard Lovelace, in his lines on ‘Peinture’, composed as a panegyric to his friend Lely, sympathized with him for the ‘transalpine barbarous Neglect’ with which such early pictures had been treated in England: an ‘un-understanding land’ where patrons were only interested in their ‘varnish’d Idol-Mistresses’ or ‘their own dull counterfeits’.

After Lely began to concentrate on portraiture in London, it is unlikely that he painted more than a few subject pictures. His finest is the Sleeping Nymphs by a Fountain (?c. 1650; London, Dulwich Pict. Gal.): its composition and types are still fundamentally Dutch, but on a bigger scale than Poelenburgh’s little pictures. It reveals an awareness of van Dyck; and, although awkwardly put together, the handling throughout is extremely sensuous, the colour rich and the lighting dramatic. These qualities are seen in the more individual and poetic Concert (London, Courtauld Inst. Gals), which contains obvious allusions to the painter’s fondness for music (he liked to have music playing while he worked) and reminiscences of 16th-century concerts champêtres and of the Utrecht school which he admired. As late as 1654, he painted the Music Lesson (priv. col., see 1978 exh. cat., p. 48), van Dyckian in its treatment of the draperies, but akin to Gabriel Metsu in design and subject-matter. Lely’s finest essays in this vein are the beautifully painted pictures of musicians (e.g. two in London, Tate), one of which perhaps represents the painter himself playing the lute (priv. col., see 1978 exh. cat., p. 42). Combining a Dutch spirit, a certain van Dyckian elegance and considerable tender charm, they are among Lely’s most personal pictures and present him in an unusually appealing light.

Lely was fortunate, in his first years in London, that, after the death of William Dobson in 1648, there were no serious rivals in the field of portraiture. Lely secured the patronage of a group of rich and cultivated noblemen—the earls of Leicester, Salisbury, Pembroke and Northumberland—who had been prominent at court before the Civil War, but had remained in London during the conflict. Their collections were temporarily intact, and Northumberland and Pembroke had been important patrons of van Dyck, whose work Lely would have had the opportunity to study at leisure in their houses. Van Dyck’s influence on him at this time is unequivocal, and it was to be the foundation of his style—of his sense of scale, his handling, his repertory of design and accessories, his marvellous ease or ‘careless Romance’—until the end of his life. Northumberland commissioned portraits of members of his family to hang as sequels to the portraits van Dyck had painted for him some ten years earlier. Though van Dyckian in pattern, the figures in Lely’s early portraits are stiffly articulated and the draperies hang awkwardly; their relationship with the underlying forms are unclear and the designs have nothing of van Dyck’s assurance. However, they have a charming freshness, the colour is subtle and individual, and the handling assured. In the latter two aspects of his craft Lely was already superior to any other painter in England, as can be seen in the most important pictures he painted for Northumberland: Charles I with the Duke of York (London, Syon House), for which Lely was paid £20 in 1648, and the Children of Charles I (Petworth House, W. Sussex, NT), probably painted in 1647 and possibly originally a commission from the king. The implicit tragedy in the first is enhanced by the lack of the sinuous rhythms with which van Dyck would have handled such a composition; but the canvas displays the richness and spontaneity of Lely’s touch at this period in such passages as the richly impasted silver lace on the Duke of York’s warm grey doublet. The group of the royal children is to some extent a reworking of a group of the royal children painted by van Dyck in 1635 (a work Lely later briefly owned), but the creamy texture, strong lighting and romantic landscape are impressive personal—essentially Dutch—qualities grafted on to the Flemish tradition of van Dyck. These qualities are also evident in two beautiful, slightly later, essays on an Arcadian theme, visual parallels to the pastoral verse of the period: the Little Girl in Green (Chatsworth, Derbys) and Henry Sidney (Penshurst Place, Kent), perhaps the finest portraits of children painted in England before the age of Reynolds and Gainsborough.

Lely continued to enjoy steady patronage throughout the Commonwealth (1649–60), not least from such royalist families as the Capels, Dormers and Somersets. He painted a series of three-quarter-length portraits (c. 1651) for Elizabeth Murray, Countess of Dysart, which still hang in the Long Gallery at Ham House, Surrey. (She was a friend of Oliver Cromwell, of whom Lely produced an official portrait in 1654 (Birmingham, Mus. & A.G.).) One of the portraits of Lady Dysart herself is closely based on a splendid portrait by van Dyck, Henrietta of Lorraine (London, Kenwood House), which had been in the collection of Charles I. In another portrait in the set, wrongly inscribed as representing the statesman Sir Henry Vane, Lely used a more sombre range of tones—rich blacks and whites against creamy flesh and a plain background—reminiscent of such Dutch artists as Bartholomeus van der Helst, Jacob van Loo or Jacob Adriaensz. Backer. In the portrait of a young man reasonably identified as John Leslie, 7th Earl of Rothes in the same collection, Lely’s inability at this date to fit a head carefully painted from life on to a conventional posture is palpable, but the series as a whole makes a rich impression. In their fine Baroque frames the portraits foreshadow the sets of portraits that Lely was to paint after the Restoration.

At least two of the young men painted for Lady Dysart’s gallery were active members of the ultra-royalist ‘Sealed Knot’; and during a visit to Holland in the summer of 1656 with his friend, the royalist Hugh May, Lely may have made contact with the English court in exile. May was a lifelong friend and Lely later painted a Self-portrait in his company (c. 1675; priv. col., see 1978 exh. cat., p. 67). Earlier, in 1653, Lely had submitted to Parliament a scheme for an ambitious decorative scheme in the palace of Whitehall: a series of pictures commemorating the most memorable achievements of the Parliament; pictures of the principal battles and sieges of the Civil War; portraits of the leading commanders; and group portraits of the Council of State and the ‘Assemblie of Parliament’.

(ii) Maturity, late 1650s and after.

Lely’s style did not attain complete maturity until the late 1650s, by which time he had achieved a satisfactory synthesis between his own, essentially Dutch, abilities as a painter and a reinterpretation, albeit less refined, of the elegance he admired in van Dyck. On the eve of the Restoration he produced portraits of complete assurance and exceptional splendour; but the poetic element, so often a feature of his earlier pictures, tended to disappear under the increasing pressure of demands on his time and, probably, in the worldly atmosphere of the restored Stuart court. There are, for instance, fine passages in the group portrait of the Perryer Family (1655; Chequers, Bucks), but the elements of this sombre composition are clumsily assembled. By contrast, the splendid Cotton Family (1660; Manchester, C.A.G.) is brilliantly lit, and the individual members of the family, as well as the group as a whole, are handled with confidence. This increased self-confidence can also be sensed in the Self-portrait (London, N.P.G.) painted at this time. The most sumptuous portraits of this period are those of the Duke of York and his Duchess, Anne Hyde (both Edinburgh, N.P.G.), painted soon after their marriage was made public in December 1660. Lely’s handling was then at its most sensuous, his surface loaded with finely controlled liquid medium: the Duke in buff with a crimson sash, grey breeches with blue ribbons at his knee against rich golden-brown and brown-grey curtains; the Duchess in a deep yellow dress with a bright blue cloak against a deeper red-gold curtain. In the background of her portrait, and behind those of the Perryer and Cotton families, are examples of the elaborately carved pieces of Netherlandish Baroque sculpture that Lely often used to enrich his work.

In October 1661 Lely was granted by Charles II an annual pension, as Principal Painter, of £200, and in the summer of 1662 he was naturalized. Because Lely’s portraits illustrate so blatantly the most familiar aspects of the court of Charles II, they have been cited in well-known descriptions of the atmosphere of that court: by Pope, for instance, in his Imitations of Horace (‘In Days of Ease, …/Lely on animated Canvas stole/The sleepy Eye, that spoke the melting soul’). One early printed account of his career describes his sound drawing, fine colour, varied and graceful postures and flowing draperies; but also ‘the languishing Air, long Eyes, and a Drowzy Sweetness peculiar to himself, for which they reckon him a Mannerist’. A contemporary wrote that after Lely had painted Barbara Villiers, Duchess of Cleveland, the most beautiful and notorious lady at court, ‘he put something of Clevelands face or her Languishing eyes into every one Picture, so that all his pictures had an Air one of another, all the Eyes were Sleepy alike. So that Mr Walker ye Painter swore Lilly’s Pictures was all Brothers & Sisters.’ Such criticisms were probably prompted by the sets of female portraits (all including the Duchess) that Lely was producing at this period: the celebrated Beauties (London, Hampton Court, Royal Col.), painted for the Duke of York; the portraits commissioned by the Grand Duke of Tuscany (Florence, Uffizi); or the set compiled by Robert Spencer, 2nd Earl of Sunderland, for the gallery at Althorp House, Northants. Lely’s assured draughtsmanship, fine colour and the flamboyant Baroque of his mature style are clearly seen in these sets. Moreover, van Dyck’s continuing influence is evident, for instance, in the confident glance, swinging movement and fluttering drapery in Lely’s Duchess of Cleveland at Althorp, almost certainly a reflection of van Dyck’s portrait of Mrs Endymion Porter (London, Syon House), which Lely would have seen in Northumberland House.

In contrast to these perhaps over-familiar works, Lely produced portraits of a more serious nature. Sir William Temple (priv. col., see 1978 exh. cat., p. 56), for example, is distinguished by an air of good breeding which Reynolds would have been glad to achieve; and a portrait such as John Maitland, 1st Duke of Lauderdale (Edinburgh, N.P.G.) has a formidable presence and sheer power in execution that would have been difficult to surpass anywhere in Europe at that time. In Lely’s sets of male portraits painted in the 1660s, likenesses of some of ‘the most illustrious of our nation’ commissioned by Edward Hyde, 1st Earl of Clarendon (now dispersed), or the famous portraits (London, N. Mar. Mus.) of the flag-officers who had served under the Duke of York in the Battle of Lowestoft, he produced a succession of interesting designs and, in the naval series, likenesses of these severe and puritanical seamen as formidably impressive as the portraits of their adversaries by van der Helst or Nicholas Maes. ‘Very finely they are done indeed’ was Samuel Pepys’s comment.

In Lely’s work of the late 1670s the colour is muted, there is less pigment on the canvas than hitherto and the paint is fused to achieve a softened, atmospheric quality across the composition. The sense of character is sensitive, occasionally surprisingly penetrating, but the articulation of the figures is sometimes more angular than in the richly composed portraits of the Restoration period. For instance, in such portraits as the Duchess of Argyll (Ham House, Surrey, NT) or the Duchess of Portsmouth (Malibu, CA, Getty Mus.) there is an artificial air that may reflect the influence of Simon Verelst or Henri Gascars. In the late full-length portraits, such as the pair depicting Henry Howard, 6th Duke of Norfolk and Jane Bickerton, Duchess of Norfolk (both 1677; Arundel Castle, W. Sussex), the elements of van Dyck’s stagecraft are adapted to a new court style, which was to survive into the last years of the century. In the very late portrait of Sir Richard Newdegate (Arbury Hall, Warwicks) Lely’s powers are still impressive: the characterization is vivid, the drawing crisp and fluent, the impasto applied with a masterly touch. The sitter is placed within a painted oval, a convention that Cornelis Jonson van Ceulen had first made popular in England; Lely himself had used it on many occasions, enriching it at this period by carving it into decorative scrolls and garlands. While established designs were produced in quantity in the studio, Lely continued to evolve new patterns to the end of his life. Outstanding portraits from his last years, all painted in subdued tones and with a restrained touch, are Sir Thomas Isham (late 1670s; Lamport Hall, Northants), with its swinging sense of movement, Sir Thomas Grosvenor (priv. col., see 1978 exh. cat., p. 71), charming and well-bred, and the 3rd Earl of Dysart (Weston Park, Salop), with the sitter’s disillusioned air and relaxed, almost louche, posture. Two of these works are signed. Lely’s signature, either the monogram PL or the full name with initials conjoined, occurs only on works of exceptional quality.

In January 1680 Lely was knighted. By then the success of Kneller was probably beginning to prey on his mind. Anxiety and the unrelenting pressure of work perhaps brought on the apopletic fit that struck Lely down at his easel. He was buried in St Paul’s, Covent Garden, on 7 December 1680.

2. Working methods and technique.

From the time of the Restoration Lely was formidably busy. When Pepys called on him on 20 October 1662, Lely said he would not be at leisure for three weeks; and when Pepys visited him again on 18 July 1666 with Sir William Penn, who was to be included in the Duke of York’s series, the painter could only offer an appointment six days later between 7.00 and 8.00 a.m. When the contents of Lely’s studio were sold, his executors catalogued, as original works, over 70 three-quarter-lengths, more than 14 heads and 3 full-lengths; there were also more than 170 copies (including 12 portraits of the King, 10 of the Duke of York, 10 of his first Duchess and 12 of the Duchess of Cleveland): evidence of well-organized production and unbroken success.

(i) Studio practice.

To cope with the enormous pressure of work, Lely had to rely on a body of apprentices or assistants, to whom he often entrusted the completion of a portrait after he had selected the design and painted the head. The young Robert Hooke was apprenticed to him for a short time in 1648. Thereafter the number of studio assistants must have increased. The most talented was probably John Greenhill. John Baptist Gaspars ( fl 1641–92) and Gerrit Uylenburgh were among the assistants employed to paint drapery. Prosper Henry Lankrink and, for a short time, Nicolas de Largillierre were among specialist painters in Lely’s studio. Mary Beale was a friend and a close observer of Lely’s method in the later part of his career; and her own work was much influenced by what she learnt under Lely’s guidance.

Once a sitting had been arranged, the patron would be shown a rapid chalk drawing with a suggested pose, similar to those made by van Dyck. But Lely’s drawings of this type are more richly worked; in one case (Paris, Fond. Custodia, Inst. Néer.), probably associated with a commission of 1661, part of the figure is painted in oil. Possibly to guide his assistants, Lely also sketched hands, a section of drapery or a piece of sculpture for use in a background. After the posture had been selected, sittings would take place. The head was painted from life, Lely at his easel six feet from the window of his studio, the light falling over his left shoulder, the sitter also six feet both from the light and the painter. While the sitter was still in the studio, Lely sketched the remainder of the composition on the canvas and laid in the colouring of hands and garments.

Some patrons were naturally apprehensive that commissions to Lely might be entrusted to assistants. In December 1677 the artist wrote to assure Sir Richard Newdegate that pictures he had ordered had been ‘from Beginning to ye end drawne with my owne hands’. There are many portraits that Lely did indeed paint throughout himself, and he would always paint at least the prototype of a new pattern; but a Study of the Head of the Duke of York (London, N.P.G.) indicates the extent to which he was involved when under pressure: the face is completed, the hair and cravat only slightly suggested. In the finished works it is often possible to discern the point at which an assistant took over. The draperies and backgrounds in the Duke of York’s portraits, for example, are competently drawn and painted but lack the freshness of touch that Lely himself would have given to the canvas, notably to the whites.

(ii) Drawings.

Lely’s distinction as a painter, and a reason for his continuing success, is partly the result of his sound draughtsmanship. Among the professional portrait painters in Stuart England, he was the finest draughtsman after van Dyck. Apart from drawings made in the course of carrying out a commissioned portrait, he produced a number of informal heads in black and red chalk, heightened with white, on brown or grey-brown paper. Good examples are the Portrait of a Girl or that of Sir Charles Cotterell (both London, BM); the finest is the youthful Self-portrait in the possession of Lely’s descendants (see 1978 exh. cat., frontispiece). These drawings are frequently signed and were conceived as portraits in their own right, to be framed (usually in ebony) and hung in a small room. They reveal an unexpectedly charming side of Lely; and they helped to establish a tradition of small-scale portraiture subsequently developed in England by Greenhill, Ashfield and Lutterell. Lely also produced a series of drawings of figures from the procession of the Order of the Garter, executed in black chalk heightened with white on blue-grey paper (dispersed; 31 are known). They are not linked with any documented commission and may record an actual procession watched by Lely soon after the Restoration (all the figures move from right to left). Essentially Dutch in manner, they are perhaps the finest drawings of their kind to have been executed in England after the death of van Dyck.

3. Collection.

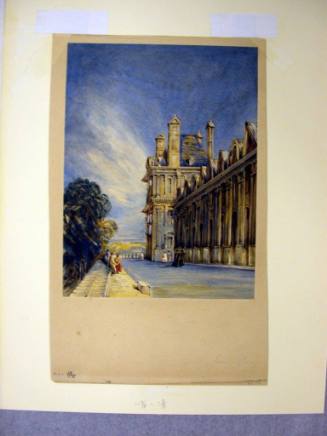

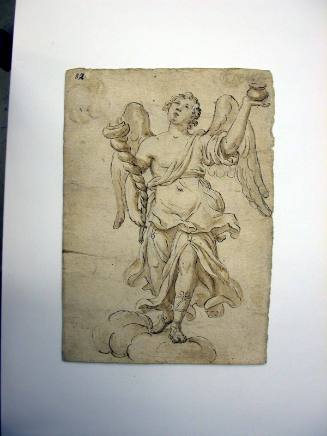

From the time he arrived in London, Lely was acquiring paintings, prints, drawings and sculptures. He made purchases from the collections of Charles I, Thomas Howard, 2nd Earl of Arundel, Nicholas Lanier and van Dyck; it is likely that he also bought from agents based abroad. Lely’s collection was strongest in 16th- and 17th-century Italian, Dutch and Flemish works, as were most English collections of this period, although some 16th-century German and 17th-century French artists were also represented. Bainbridge Buckridge, who believed that Lely’s acquisitions were his substitute for foreign travel, considered them to be ‘the best chosen Collection of any of his Time’, adding that the benefit Lely gained from them ‘may sufficiently appear by that wonderful stile of Painting which he acquired by his daily conversing with the works of those great men’. Following Lely’s death and faced with a burden of nearly £9000 in debts and legacies, his executors organized the sale of his collection by auction. The pictures were valued by Parry Walton ( fl c. 1660–1700) and John Baptist Gaspars, both of whom had been Lely’s assistants. Copies of the descriptive catalogue written by one of the executors, the writer and lawyer Roger North, were sent to the Netherlands, France and Italy. The pictures and sculptures were placed on view at Lely’s Covent Garden studio for 14 days before the sale, which opened on 18 April 1682. Besides Lely’s own works, the paintings included works by or attributed to Veronese, Correggio, Hans Holbein the younger, van Dyck (e.g. Lady Elizabeth Thimbleby and Dorothy, Viscountess Andover, London, N.G.), Claude Lorrain, Pieter van Laer and Adriaen Brouwer; among the sculptures was Bernini’s bust of Mr Baker (London, V&A). At the close of the four-day sale all works had been sold for over £6000.

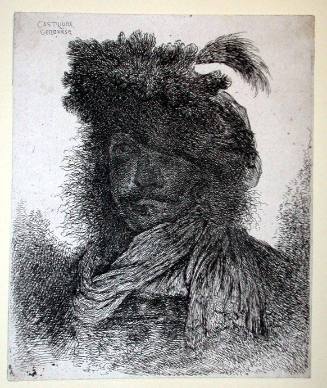

Lely’s collection of prints and drawings, one of the first to be formed in England by a painter–collector, was described by the artist Charles Beale as ‘the best in Europe’; it included drawings by Leonardo da Vinci, Fra Bartolommeo, Raphael (e.g. Constantine Addressing his Troops, Chatsworth, Derbys; now considered a school work), Correggio, Giulio Romano, Polidoro da Caravaggio, Parmigianino (over 100 figurative and drapery studies), Veronese, Primaticcio, Federico Barocci, Taddeo and Federico Zuccaro, the Carracci, Rubens and van Dyck (including his Italian Sketchbook, London, BM). Here again, works by Italian, Dutch and Flemish artists predominated, although Lely did own a number of German drawings (e.g. by Hans Rottenhammer) and a few English drawings by Isaac Oliver and his son Peter. The prints and drawings (c. 10,000 items, each sheet marked by North with the distinctive pl stamp) were dispersed in two mixed sales on 11 April 1688 and 15 November 1694 and fetched over £2400.

4. Critical reception and posthumous reputation.

Lely was a rich and successful man. At the end of his career he was charging £60 for a full-length portrait and £40 for a three-quarter-length. (For full-lengths at this time Michael Wright and Gerard Soest probably charged £36 and £30 respectively; by 1691 Kneller was asking £50 for a full-length and only by 1706 was he asking £60. Van Dyck had usually received £30 for a three-quarter-length and £50 to £60 for a full-length.) Lely owned property in Surrey and Lincolnshire, as well as his share of the family’s property in Holland. He lived in a grand way in Covent Garden: ‘a mighty proud man, and full of state’, in Pepys’s well-known aside.

At the time Lely painted Cromwell in 1654, he was described as ‘the best artist in England’. There were nevertheless occasional references to his failure to catch a satisfactory likeness. Dorothy Osborne reported to William Temple in October 1653 that Lely had been ‘condemned for makeing the first hee drew for mee a little worse than I, and in makeing this better hee has made it as unlike as tother’, and in 1655 Henry Osborne complained that in Lady Diana Rich’s portrait ‘one of the eyes was out, so I said onely that Mr Lilly should mend it’. Such criticisms persisted. Pepys, who saw him painting the Duchess of York on 24 March 1666, considered that even after two or three sittings the likeness eluded the painter. Dryden, in his preface to Sylvae (1685), wrote of ‘the late noble painter … who drew many graceful pictures, but few of them were like. And this happened to him, because he always studied himself more than those who sat to him.’ On the other hand, Sir Thomas Isham was assured in 1679 that Lely’s portrait of him was ‘extreme like’.

The burdens of the portrait practice and the demands of the leaders of society in Restoration London may have bred a vein of cynicism in Lely. Jonathan Richardson the elder, in his Essay on the Theory of Painting of 1715 (p. 228), recorded a conversation between the painter and a friend: ‘For God’s sake, Sir Peter, how came you to have so great a reputation? You know that I know you are no painter’. ‘My Lord, I know I am not, but I am the best you have’. In fact Lely’s best work, throughout his career, is fit to be set beside that of any portrait painter working in a comparable situation on the Continent. The finer qualities, of observation as well as of technique, in Lely’s work have been obscured in the eyes of posterity by the seeming uniformity of his work and, even more, by the enormous number of inferior pictures with which his name, often unfairly, has been linked. Painters working early in the following century held his work in high esteem: Gerard de Lairesse, for example, called him ‘the great Lely’. Later his work formed part of an inheritance of which van Dyck’s achievement naturally formed the richest part; but in borrowings by Reynolds from that inheritance, Lely’s legacy is often in evidence. Those later critics, from George Vertue to C. H. Collins Baker, who investigated his work in detail and with sympathy, never questioned his outstanding ability.

Oliver Millar and Diana Dethloff. "Lely, Peter." In Grove Art Online. Oxford Art Online, http://www.oxfordartonline.com.proxy.lib.fsu.edu/subscriber/article/grove/art/T050209 (accessed May 1, 2012).

Person TypeIndividual

Italian, c. 1610 - 1665