Matthew Boulton

English, 1728 - 1809

English manufacturer and engineer. At the age of 17 he entered his father’s silver stamping and piercing business at Snow Hill, Birmingham, which he inherited in 1759. His marriage in 1756 brought a considerable dowry, providing capital for the establishment in 1762 of his factory in Soho, Birmingham, in partnership with John Fothergill (d 1782). Boulton progressed from the production of ‘toys’ in tortoiseshell, stone, glass, enamel and cut steel to that of tableware in Sheffield plate, on which he obtained a monopoly, and later ormolu (e.g. two pairs of candelabra, c. 1770; Brit. Royal Col.; London, V&A) and silver, and enjoyed a reputation for fine craftsmanship. By 1770 his firm, known as Boulton & Fothergill, had nearly 800 employees and had mercantile contacts in virtually every town in Europe. His social, political and trade connections facilitated the establishment of assay offices in Birmingham and Sheffield in 1773, and in the former city Boulton’s firm became one of the largest manufacturers of silver and Sheffield plate.

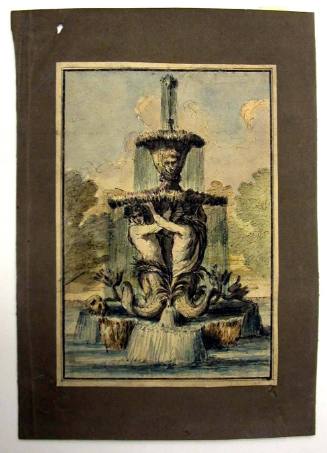

Boulton & Fothergill produced some of the best-designed plate and silver in the last quarter of the 18th century and fully exploited the technical advances of Joseph Hancock and R. A. F. de Réaumur. The thinner gauges of Sheffield plate available from the 1770s, and the precision of machine-produced, fly-punched parts that were cut, stamped and pierced in repeated patterns were suitable for regular, uniform Neo-classical designs, in which a clear distinction can be discerned between structure and decoration. As the items produced in silver, for example dinner services, tureens, coffee- and teapots and candelabra, were made increasingly for stock rather than to order, Boulton also adopted the manufacturing techniques of items in Sheffield plate for those in solid silver, especially for objects with simple forms requiring little chasing or hand-finishing. Notable among Boulton’s products are a silver helmet-shaped ewer (1774; Birmingham, Mus. & A.G.), a similar silver-gilt ewer (1776; Boston, MA, Mus. F.A.), a pair of silver sauce tureens (1776; Birmingham, Assay Office), and a pair of Sheffield plate candelabra (1797; Birmingham, Mus. & A.G.). Many of his pattern books are in the Reference Library, Birmingham. Boulton trained his employees to his own processes rather than take on apprenticed silversmiths, and for silverware he used designs by the silversmiths Thomas Heming and Michelangelo Pergolesi ( fl 1777–1801) and such architects as Robert Adam, who designed a set of eight sauceboats (1776–7; one London, V&A; see ), James Adam, William Chambers, Robert Mylne, James Stuart and James Wyatt. Boulton’s die-sinkers and medallists included the Frenchman jean-pierre Droz and the German Conrad Heinrich Küchler (d 1821). Later distinguished silversmiths whom Boulton trained were Edward Thomason (1769–1849) and Benjamin Smith (1764–1823). Boulton also collaborated with his friend Josiah Wedgwood, who used similar design sources, production methods and marketing techniques and produced cut-steel frames for jasper cameos (examples in London, V&A).

Boulton was less a craftsman and designer than an industrial entrepreneur, organizing factory production of metalwork and managing designers both within and outside his extended workshop system, thereby revolutionizing the silver manufacturing trade and challenging the monopoly of silversmiths in London. He produced silver and Sheffield plate to the highest technical standard in the most fashionable styles and made such small wares as buckles and fittings available to a wider market. A large part of the production of silver, however, continued to consist of ornamental pieces that were expensive to produce. His production of ormolu, which ceased in the 1780s, was only partially successful, as he tried to compete with French manufacturers. As the processes involved in the manufacture of ormolu were not suited to mass-production, this part of his business failed to be profitable.

Towards the end of his life Boulton concentrated on his engineering enterprises. By 1787 his input of capital and the technical expertise of James Watt (1736–1819) enabled the widespread use of the steam engine, superseding water-power, for operating mechanical lathes and stamps, thereby increasing production up to tenfold. In Birmingham Boulton was co-founder of the Lunar Society and in London a fellow of the Royal Society. His scientific and intellectual friends included Sir Joseph Banks, Erasmus Darwin (1731–1802), Richard Lovell Edgeworth (1744–1817), Benjamin Franklin (1706–90), Samuel Galton, Sir William Hamilton (i), Sir William Herschel (1738–1822) and Joseph Priestley (1733–1804). The factory, known from 1781 as the Matthew Boulton Plate Co., continued after his death, producing such pieces as J. Widdowson’s silver copy (1827; Birmingham, Assay Office) of the Warwick Vase (2nd to 4th century AD; Glasgow, Burrell Col.); it remained in operation until the 1840s and was sold in 1850.

Richard Riddell. "Boulton, Matthew." In Grove Art Online. Oxford Art Online, http://www.oxfordartonline.com.proxy.lib.fsu.edu/subscriber/article/grove/art/T010497 (accessed May 1, 2012).

Person TypeIndividual