Joseph Wright

British, 1734 - 1797

English painter. He painted portraits, landscapes and subjects from literature, but his most original and enduringly celebrated works are a few which reflect the philosophical and technological preoccupations of the later 18th century and are characterized by striking effects of artificial light. He was the first major English painter to work outside the capital all his life: apart from spells in Liverpool (1768–71), Italy (1773–5) and Bath (1775–7), he lived and worked in his native Derby, though exhibiting in London at both the Society of Artists (1765–76, 1791) and the Royal Academy (1778–82, 1789–90, 1794). Reappraisal of his achievements has followed Nicolson’s monograph of 1968.

1. Early career, to 1773.

Wright was the third son of a Derby attorney. He trained as a portrait painter in the London studio of Thomas Hudson from 1751 to 1753, then returned to Derby where he painted a penetrating, detached Self-portrait (c. 1753–4; Derby, Mus. & A.G.) in van Dyck costume, as well as portraits of his relations, friends and members of prominent local families. During a further period of study with Hudson (1756–7) he became friends with John Hamilton Mortimer. In Derby, Wright continued to paint members of the rising middle classes, professional people and local landed gentry; such portraits would form his main source of income throughout his career. In 1760 he attracted a number of portrait commissions by travelling through the Midland towns of Newark, Retford, Boston, Lincoln and Doncaster. In addition to half- and three-quarter-length single portraits, Wright began to paint more ambitious group portraits, such as James and Mary Shuttleworth with One of their Daughters (1764; Lord Shuttleworth priv. col., see 1990 exh. cat., p. 45). He painted without the help of studio assistants and sometimes enhanced his compositions with poses borrowed from Old Masters such as Rembrandt or Raphael; this and his excellence at rendering drapery make his portraits often attractive, despite a directness of approach that can rarely have flattered.

Alongside the portraits Wright began in the early 1760s to paint subject pictures of figures in dark interiors illumined by candles or lamps. Their dramatic contrasts of light and shade, derived from masters such as Rembrandt, Gerrit van Honthorst, Godfried Schalcken and ultimately Caravaggio, give these images great clarity of form and detail as well as powerful visual impact, as for instance in the Three Persons Viewing the ‘Gladiator’ by Candlelight of 1765 (priv. col., see 1990 exh. cat., p. 61). The largest and most unusual of these scenes are A Philosopher Lecturing on the Orrery (1766; Derby, Mus. & A.G.) and Experiment on a Bird in the Air Pump (1768; London, Tate). The philosopher in the first shows the movements of the solar system, through a type of model named after the Earl of Orrery, to a group of laymen whose faces are lit up by the lamp that represents the sun. In the second a scientist demonstrates the nature of a vacuum by pumping the air from a glass vessel containing a bird, eliciting responses ranging from the detached concentration of male observers to the distress of two young girls concerned for the suffering bird. These works, embodying the wide contemporary enthusiasm for scientific and technological development, were unique in their combination of the scientific portrait group—recalling Rembrandt’s Anatomy Lesson of Dr Tulp (1632; The Hague, Mauritshuis)—expressive depiction of emotion in a contemporary popular setting and striking Caravaggesque contrasts of light and shadow. The accurate depiction of scientific equipment and processes reflects Wright’s personal acquaintance with Midlands figures such as the polymathic Erasmus Darwin, scientist and poet, the pottery manufacturer Josiah Wedgwood and the Derby mechanic and geologist John Whitehurst (1713–88), who, with others like Matthew Boulton and James Watt (1736–1819), formed the Lunar Society c. 1764–5. The group promoted theoretical discussion, but with a view to practical improvements in trade and industry.

Joseph Wright of Derby: A Philosopher Lecturing on the Orrery, oil on canvas, 1.47×2.03 m, 1766 (Derby, Museum and Art Gallery); photo credit: Giraudon/Art Resource, NY

The scientific scenes established Wright’s reputation in London and, following them, many of his major pictures were engraved by William Pether, Valentine Green, John Raphael Smith and others. He was, however, based in Liverpool from 1768 to 1771, producing paintings for Radbourne Hall, Derby, in 1770 with his friend Mortimer. He continued to paint portraits of Midlands and northern sitters, the finest of which is perhaps of his friends Mr and Mrs Coltman (?1771; London, N.G.), who, recently wed, are shown about to set out riding in a landscape setting recalling Gainsborough’s open-air portraits. Between 1771 and 1773 Wright painted several nocturnal scenes, again combining modern subjects with a historical style. The moonlit tumbledown building in Blacksmith’s Shop (1771; two versions, New Haven, CT, Yale Cent. Brit. A. and Derby, Mus. & A.G.) recalls traditional nativity settings, while the muscular workmen illumined by the glowing ingot, here and in Iron Forge (1772; London, Tate, see 1990 exh. cat., p. 102) with its introduction of modern machinery, elevate the subjects from popular genre towards the level of the modern history painting being simultaneously introduced in America by Benjamin West. Further nocturnes, Iron Forge Viewed from Without (1773; St Petersburg, Hermitage)—bought from Wright for Catherine the Great—and the Earthstopper on the Banks of the Derwent (1773; Derby, Mus. & A.G.), influenced by such Dutch landscape painters as Aert van der Neer, show, like Mr and Mrs Coltman, a newly developing interest in landscape.

Other paintings from the same period present melancholy scenes of man confronted by death, inspired by literary sources. Philosopher by Lamplight (‘Hermit Studying Anatomy’, 1769; Derby, Mus. & A.G.) recalls Salvator Rosa’s Democritus (Copenhagen, Stat. Mus. Kst.), Dürer’s Melencolia engraving and the hermits of 17th-century artists like Gerard Dou, but Wright was probably also influenced in his choice of imagery by the 18th-century British ‘graveyard’ poets—Robert Blair, Edward Young and Thomas Gray. Another nocturne, Miravan Breaking Open the Tomb of his Ancestors (1772; Derby, Mus. & A.G.), seems to derive from an as yet unidentified literary source; its macabre romanticism is close in spirit to the work of Mortimer and of Johann Heinrich Fuseli, and to the contemporary Gothic novel. A third subject in the same vein, the Old Man and Death (1773; Hartford, CT, Wadsworth Atheneum), illustrates one of Aesop’s Fables; an alarmed old man, seated by a ruin in a daylight landscape, faces Death in the form of a skeleton standing before him.

2. Voyage to Italy and later career.

In October 1773 Wright departed for Italy, arriving in Rome in February 1774 with his pupil Richard Hurlestone (d 1777), the portrait painter John Downman and the sculptor James Paine (1745–1829). Here he made friends with George Romney, Ozias Humphry and Jacob More. A common enthusiasm for Michelangelo, as advocated by Fuseli who was currently working in Rome, led Wright and Romney to make studies from the Sistine Chapel. During his two years based in Rome, Wright sketched Classical sculptures and architecture (drawings, Derby, Mus. & A.G.; London, BM; New York, Met.) and recorded the city’s spectacular Girandola or annual firework display (1774; Derby, Mus. & A.G.). He also sketched scenes in the Campagna and in the Kingdom of Naples, including grottoes in the Gulf of Salerno and an eruption of Vesuvius witnessed in October 1774. Oil paintings from this material were mostly produced following his return to England, via Florence and Venice, in September 1775. Vesuvius inspired over 30 paintings during the next 20 years (e.g. 1778; Moscow, Pushkin Mus. F.A.), in which Wright probably drew on the work of the French specialist in the volcano, Pierre-Jacques Volaire, but was more generally influenced by Edmund Burke’s concept of the Sublime. The contemporary scientific fascination with volcanoes is also seen in William Hamilton’s Observations on Mount Vesuvius (1772) and the work of Wright’s geologist friend Whitehurst. Wright’s later, sunlit Italian landscapes of the 1780s and 1790s are close in conception to the classical landscape manner of Richard Wilson, and his coastal scenes recall those of Claude-Joseph Vernet.

Wright spent the two years after his return in 1775 in Bath, in an unsuccessful attempt to replace the recently departed Gainsborough as portrait painter to fashionable society. After his permanent return to Derby, he was elected ARA in 1781; but he quarrelled with the Royal Academy in 1783, apparently over election to full RA status. In keeping with the fashion set by Gainsborough and Romney, his later portraits are more penetrating in their characterization, often more complex in their iconography and generally more subdued in colouring. The exceptional informality and melancholy pose of Brooke Boothby (1781; London, Tate), a philosophical Staffordshire nobleman seen reclining by a woodland stream, clutching a volume by his friend Jean-Jacques Rousseau, make for one of the most singular images in 18th-century art of man retreating into communion with nature, the theme of Rousseau’s writings. The Rev. D’Ewes Coke, his Wife Hannah and Daniel Parker Coke MP (1782; Derby, Mus. & A.G.) and the Rev. Thomas Gisborne and his Wife Mary (1786; New Haven, CT, Yale Cent. Brit. A.) are seen as genteel amateur artists, on sketching trips in the countryside. Wright also painted imposing portraits of leading figures of the Industrial Revolution like the textile manufacturers Richard Arkwright (1789–90; priv. col., on loan to Derby, Mus. & A. G.) and Samuel Oldknow (c. 1790–92; Leeds, C.A.G.). Oldknow holds a roll of his muslin, while Arkwright is proudly seated by a model of the innovative water-powered cotton spinning frame which made his huge fortune.

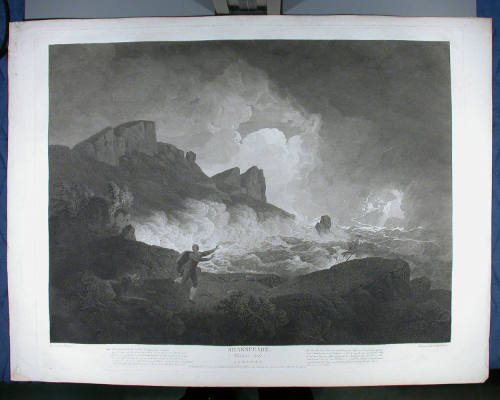

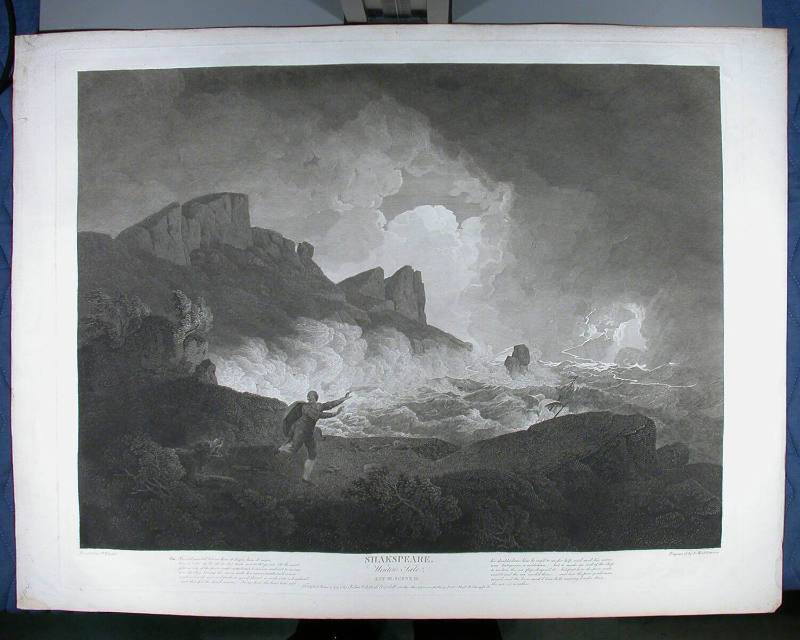

Wright increasingly depicted themes from literature in his later career. He responded to the contemporary cult of sensibility in several versions of two scenes from Lawrence Sterne’s A Sentimental Journey (1768): The Captive (e.g. 1774, Vancouver, A.G.; and late 1770s, Derby, Mus. & A.G.) and Maria (1777, priv. col., see 1990 exh. cat., p. 107; 1781, Derby, Mus. & A.G.); a prisoner languishing in his cell and a distraught village girl abandoned by her lover—both melancholy, emotive subjects. The taste for Classical themes led to Corinthian Maid (c. 1783–4; New Haven, CT, Yale Cent. Brit. A.), showing the traditional origin of painting when a potter’s daughter traced the shadow of her lover on a lamplit wall. This was a commission from Wedgwood, with some of his pottery and a kiln inserted as accessories. In the later 1780s Wright contributed three paintings to John Boydell’s Shakespeare Gallery in London, including a lamplit Tomb Scene from Romeo and Juliet (1789–90; Derby, Mus. & A.G.).

The increasingly frequent landscapes in Wright’s later output—British as well as Italian—show him seeking for truthful observation of natural phenomena, such as rock formations or effects of light and atmosphere, without sacrificing aesthetic values like poetry, beauty, drama and composition. He painted several views of Matlock High Tor (e.g. mid-1780s; Cambridge, Fitzwilliam) and other rocky parts of Derbyshire. Another Derbyshire landscape, Arkwright’s Cotton Mills by Night (c. 1782; priv. col., see 1990 exh. cat., p. 199), reveals Wright once again as an innovator, giving to one of the landmarks of the Industrial Revolution an elevated treatment previously reserved for country houses. Wright’s late landscapes often show a great sensitivity to varying effects of light and weather, as in the sky suffused with pink light of the Landscape with Figures and a Tilted Cart (c. 1790; Southampton, C.A.G.) or the leaden, rain-filled sky that heightens the contrasts of the Landscape with Rainbow (c. 1794–5; Derby, Mus. & A.G.). A visit to the Lake District in 1793 or 1794 inspired a series of poetic views, including Rydal Waterfall (1795; Derby, Mus. & A.G.) and Derwent Water (1795–6; New Haven, CT, Yale Cent. Brit. A.).

David Fraser. "Wright of Derby, Joseph." In Grove Art Online. Oxford Art Online, http://www.oxfordartonline.com.proxy.lib.fsu.edu/subscriber/article/grove/art/T092356 (accessed May 2, 2012).

Person TypeIndividual