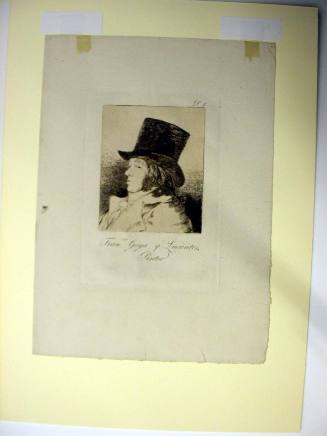

Image Not Available

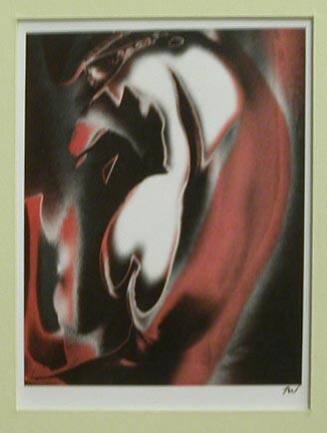

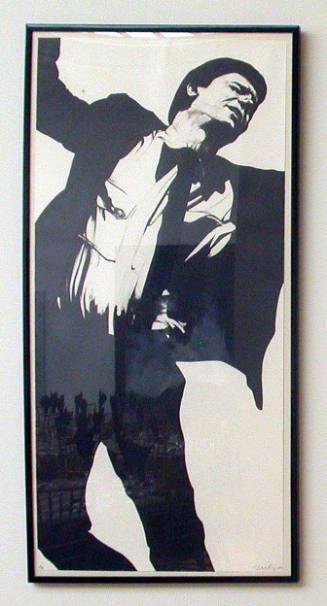

for Clyfford Still

Clyfford Still

American, 1904 - 1980

"Cantankerous Clyfford Still's Palette of Green and Black", by Katharine Kuh

The abstract expressionist painter Clyfford Still had few friends in the art world, but the late critic Katharine Kuh was one of them. This essay was adapted from a book of reminiscences Kuh was working on at her death in 1994.

Clyfford Still was an outspoken man periodically tormented by repressed fury. He was far from easy to get along with. Most dealers, museum personnel and colleagues eventually bowed out or more likely were booted out by him. He chose to isolate himself from an art world he despised, yet he and I remained friends without a break in our long association. No doubt my unbounded admiration for his paintings was largely responsible for such staying power.

At times I found Still's writings on art a bit unhinged, as when he insisted that the Armory Show was a dumping ground for the "sterile conclusions of Western European decadence" and termed Cezanne, Picasso, Kandinsky and Monet "monotonous." But in conversation -- art was all he ever talked about with me -- he was more lucid. Indeed, I found him a perceptive critic of his own work and that of other 20th-century artists, unless he was under some special pressure, either real or imagined. Then he could become irrationally judgmental.

Though he wrote with venom about his contemporaries of the New York School (which he helped to found), accusing them of "meanness of purpose" and "amply worthy of the contempt and hatred they secretly exchange with one another even unto their deaths," he discussed them more rationally and analyzed them with considerable insight. I was often amazed at how judiciously he spoke and yet how paranoid were his writings.

When he rejected New York and what he considered its fraudulent art scene, he broke all ties and moved to a retreat in rural Maryland, northwest of Baltimore. On my first visit there sometime in the early 1960s, Clyff, even before allowing me to drop my overnight bag at the house, steered me to a barn that he'd transformed into a spotless, unfurnished space where, from time to time, he hung a few works in order to isolate and study them. That day he had installed three very large recent paintings, their color high-pitched and their presence overwhelming. They were immensely open, free, shot through with light and endless space.

His work had always impressed me as competing with rather than interpreting nature. Earlier it had seemed more cataclysmic, but now, away from New York, a certain optimism had taken over. On that visit, I stayed overnight but never again. My room, in fact every room, was stacked and packed with rolled canvases. I had nightmares imagining that in the dark I might inadvertently injure a painting or two.

I once described Still's paintings as "living organisms," their surging pigment gashed to expose bottomless voids and suspended solids. He was able to create a cosmos of his own. His individual canvases are less revealing than groups of them, a reality he understood when he gave 31 paintings to the Albright-Knox Art Gallery in Buffalo and 28 to the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, hoping that these concentrations would act as counterparts to the world of natural phenomena.

He hated good taste; he hated anything easy to label or to absorb at first glance. He felt, and probably justifiably, that he was the first to experiment with many of the New York School's most radical discoveries, though he is rarely given credit for it. This failure of other artists, namely Barnett Newman and Robert Motherwell, to acknowledge his primacy rankled enormously, and it was a source of everlasting bitterness.

Differing from Mark Rothko, whose place in future history was a consuming preoccupation, Still had no doubt that his name would endure. At one time Still and Rothko were extremely close friends. Their relationship, which started in 1943, held profound significance for both of them, but ended abruptly at least a decade before Mark's death in 1970. Rothko, who was less influenced by Still's paintings than by his thinking, was a late bloomer and was composing rather conventional city scenes when Still had already embarked on radical non-objective canvases. It was Clyff's uncompromising independence, coupled with his freedom from orthodoxy, that stiffened Mark's resolve to let himself go, to experiment, to find his own way.

Mark was not a courageous man, because he cared too much about what other people thought, but Clyff had inner strength to spare. He imparted enough to his friend so that for a time Mark had the inner strength to do what he needed to do. Clyff had helped Mark become something better than himself, and Mark was always grateful for it.

I never heard Rothko say an unkind word about the other artist, but I cannot report the same of Still. He was rancorous, and while recognizing the depth of their friendship, after the break he looked back with animus. I wasn't able to find out precisely why they split up, and despite Clyff's claim that he could no longer tolerate Mark's involvement with the New York scene and its "corrupt art market," I have always wondered if that was the true explanation. There is no doubt that Still was deeply disappointed when his friend gave in to the "contaminations" of success -- after Mark died and his business dealings with Marlborough Gallery came out into the open, I began to sympathize with Clyff's point of view a little more -- yet there is no doubt that Still was a taskmaster who balked at any concession.

When Clyff abandoned New York in 1961 and settled in Maryland, or perhaps even earlier, the friendship ended. It was, I imagine, Still's choice, for whenever I visited him, Mark sent wistful greetings and always added, "Look carefully, so you can tell me what he's doing." After I got back to New York, he always questioned me in detail about Still's recent work, for now his paintings were seldom exhibited. Rothko yearned to reinstate their friendship, but Still was uncooperative. Mark reminded me of a little boy on these occasions, peppering me with one question: "What did he say about me? What did he say?" One time he was so persistent that I broke my silence: "He said that you're living an evil, untrue life."

Toward the end of his life, Mark talked about Clyff and kept telling me that he wanted to see him. He asked me to take Clyff that message, and I agreed. I went to Maryland to see Clyff and told him how depressed and sick Mark was, how much their old friendship meant to him, and how even a brief call would make a difference, but I wasn't able to get through. He refused to visit or telephone; Rothko had to approach him personally and make his feelings known. "It's up to him," Still said. "He has to come to me." I'm afraid it was too late by then; Rothko was seriously ill and, in addition, I'm not sure that he fully understood the exact nature of their difficulties. If he did, he never told me, though we discussed Still more often than any other artist. By some strange coincidence, a few hours after Theodoros Stamos called me with the news that Mark had killed himself, Still phoned from Maryland. I naturally thought he wanted to discuss the tragedy, but, as it turned out, he had heard nothing. I filled him in and shall never forget his response. "I'm not surprised," he said. "He lost his way a long time ago."

After my first visit with Still, I went at least once each year to see him. In 1966 he and his wife, Patricia, settled in a larger white-columned house nearby in the town of New Windsor. Located next to a funeral parlor, the new home offered more space but it was rapidly filled to capacity with multiple rolled canvases, each identified by Pat with a small sketch of the original. Since the paintings were not titled (only dated), this arduous practice was necessary. Again the entire house was taken over, with only a cramped section of the kitchen reserved for sociability. I worried about the danger of fire, but Clyff claimed the paintings were safer with him than in storage. I always suspected he was too attached to be separated from them.

A visit made in late 1969 stands out, partly because I had decided that day to emancipate myself, and partly because I'd been commissioned by Vogue magazine to write an article on Clyff, so this was chiefly a business trip. Blindly opposed to critics, he had limited the field to me -- otherwise I'm sure Vogue would have looked elsewhere. Clyff always met me at the airport, well over an hour's drive from his house. A frugal man, he allowed himself only one luxury that I ever observed: He always drove a large, comfortable, conventional car, which in retrospect was probably a Cadillac. Each visit we stopped for lunch at the same small wayside restaurant, and each time I'd swallow my tongue when he'd say, "You don't want a drink, I'm sure, and the codfish balls are a specialty here -- I always take them." This time I had geared myself in advance to declare my independence. Yes, I did want a Bloody Mary, and no, I didn't want those miserable codfish balls. He was surprised but indulgent.

When we arrived at his house that day, a small sports car with the top down was parked there. He explained that it belonged to a photographer sent by Vogue to illustrate the article. I was vaguely introduced to Mr. Somebody-or-Other, sportily gotten up in a brown corduroy jacket. He was obviously British, as was his young assistant, and he amazed me with his agility. Because the canvases he photographed were very large and the rooms crowded with rolled ones, he often worked from the top of an extension ladder, Clyff having installed the un-stretched, unframed painting flat on the floor.

As I took notes, the young man took pictures. It was dark and we were all parched before Pat invited us into the kitchen for "a drink," which turned out to be weak tea and limp graham crackers. Subsequently, I was picked up by friends with whom I stayed in Baltimore. Some months later, when the article appeared in Vogue, I was amused to see that the photographer, who was given star credit, was Lord Snowden. Actually, Snowden was most deferential to Clyff, but the opposite wasn't true. Still was much too involved in his own work to be concerned with the peerage.

When Thomas Hess became head of the department of 20th-century art at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in 1978, he promptly scheduled a long overdue retrospective exhibition of Still's work, but because of Hess's premature death later that year, the project was not without complications. Though Clyff, whose standards were high and implacable, was extremely demanding, the museum made every effort to smooth his way. The director, Philippe de Montebello, was both understanding and flexible. There were innumerable small altercations and I heard about most of them because my apartment was so near to the Metropolitan that Clyff could almost use it as a way station.

But by far the most serious problem was his health. He'd been diagnosed as having a stomach tumor and advised to undergo immediate treatment. Because he felt it imperative to plan and oversee every detail of the exhibition, he insisted on delaying any surgery until after the show opened in November of 1979. Even in a life-or-death emergency, the paintings came first. "They are my way of growing and thinking," he explained, "they're my autobiography." He told me his quest was "self-discovery" and claimed that "art is the only aristocracy left where a man takes full responsibility." He went on to say, "I never wanted color to be color. I never wanted texture to be texture, or images to become shapes. I wanted them all to fuse into a living spirit."

The Metropolitan arranged a small opening luncheon in Clyff's honor. Except for members of the museum's staff and board, I recognized just a handful of guests from the contemporary art world, presumably because Clyff had vetted -- and vetoed -- the invitation list. The only important artist present other than Clyff was Saul Steinberg, who I doubt was a close friend. Possibly because his forte was draftsmanship, he had never presented Still with competitive or philosophical problems. There were a few brief speeches by various dignitaries, and then Clyff rose, his face drawn and white but still handsome in its stern clarity. Around his neck and shoulders he had draped a tan wool scarf, which he never removed during the entire proceedings. He must have been in agony, and his voice was so weak I could hear little of what he said.

The show was too large and not always the best possible selection, but for me it was a landmark experience and, let me add, an engulfing one. No decorative concession or easy solution softened the impact. Because Still was reaching out to a new dimension, his work was not uniformly resolved. For him even the modulations of matte to shiny blacks could project entire spatial sequences. And it was space he pursued through sweeping color, texture, and yawning voids.

Clyff never recovered his health. He called me one day to say that he was coming to New York to consult a doctor. Would I drop by his daughter's apartment to see him? I was shocked by his appearance. Very thin, weak, and obviously in pain, he nonetheless directed our conversation toward the usual art pros and cons with the same vigor and anger of the past, his eyes boiling, his body failing. He mentioned nothing about his condition, though I could see he was suffering. When I rose to leave, he insisted on accompanying me to the elevator. There he shook my hand and said quietly, "This is goodbye." Less than two weeks later, he died.

Clyff watched over the sale of his paintings with tenacious care and, except for the two large groups he'd given to Buffalo and San Francisco, much of his work remained in his estate. Ever struggling to outwit history, he left a complicated will stipulating that his paintings be given to an urban museum that would guarantee the facilities he demanded, such as separate physical quarters and storage, and a reliable conservator and curator. The art cannot be sold or lent, or hung with anyone's work, and a certain percentage of it must be on view at all times. And there were further requirements, all of which have made the finding of a permanent home more than difficult, especially as he left no endowment for the work's upkeep. Few museums have the space or funds to satisfy such exacting obligations, and in addition, thoughtful staffs are opposed to freezing their institutions into eternal rigidity. It is nothing less than tragic that this body of work remains unavailable to a public long denied adequate contact with it. Perhaps trusting the future is wiser than trying to control it.

Source: Askart Archives

A major abstract expressionist painter associated with the post-war California Bay Area avant garde, Clyfford Still was committed to shedding European traditions in art and to expressing his own personal thoughts and emotions through his work. Still developed a signature style, which was a combination of abstract forms suggesting both depth and flatness with no central focal point. Jagged forms appearing as though they were the same depth were all over his canvases.

He was from Grandin, North Dakota, and grew up living between Spokane, Washington in the winters and the remainder of the years on the prairie of southern Alberta, Canada where his family homesteaded. This experience was quite formative in that the environment was rigorous, and death was a constant. He hung around a preacher's library reading art books, and he also painted landscapes and did portraits of his family and other local people.

In 1928, he went to New York City, looked in briefly at the Art Students League and liked nothing that he saw because he felt that everything was reduced to examples of historical schools and was intended for rich, important people.

He returned West and graduated in 1933 from Spokane University with a major in art and then taught at Washington State University at Pullman. He felt much more in common with the music and math teachers than his fellow art instructors, and his heroes in fine art were Rembrandt, Turner, Blake and Beethoven.

Contrary to the prevalent urban realism in art led by Robert Henri in New York, Still was exceedingly confident about subject matter based on his rural background. His early painting is parallel to American Scene painting and reflects his fascination with the bigness of the land.

In the 1930s, he spent two summers at Yaddo, a retreat for artists, writers, and musicians in Saratoga Springs, New York, and from his experiences there determined to turn away from landscape painting to imaginative figure subjects in a style that was austere.

He moved into abstract expressionism, using broad and quick brushstrokes and rich textures on large-scale canvases, but unlike many of his peers, he was not interested in throwing paint on canvas but painting deeply as though he were coming out the other side. Many of these pieces had gaunt male figures, elongated and roughly executed, and looming over their surroundings.

In the 1940s, he added wiry, busy lines over forms, which were surreal and organic, amoebic appearing, and he also did watercolors and sculpture. Many of his bio-morphic works were shown at the Peggy Guggenheim Art of this Century Gallery in New York.

In the early 1940s he went West where his life was a struggle, especially since he had young family. He took work in the San Francisco shipyards and for Hammond Aircraft Company and painted in makeshift studios near Berkeley. However, he got little response to his work.

In 1943, he took a teaching job at the Richmond, Virginia Professional Institute and worked hard to clarify his vision. In 1945, he took his work to New York and made a strong impression on Mark Rothko and Peggy Guggenheim.

From 1946 to 1950, he taught at the California School of Fine Arts where he became an influence in popularizing Abstract Expressionism. It was an atmosphere of highly charged rebellion, and Still was a puzzle to many of his peers because he was so dignified and ascetic-seeming in this setting. He drank little, had few friends, and worked from an isolated studio in the school. He drove a gray Jaguar sedan, which he maintained fastidiously.

He made periodic trips to New York, keeping a direct connection between both coasts and with the New York School of Abstract Expressionism. It was not until 1947 and a one-man show at the California Palace Legion of Honor that many Californians saw Still's paintings, and viewers seemed awe struck at the violent, raw power of the canvases. Still's influence at the California School was reinforced when he brought his close friend Mark Rothko to teach there during two summer sessions.

Source:

Matthew Baigell, Dictionary of American Art

Person TypeIndividual