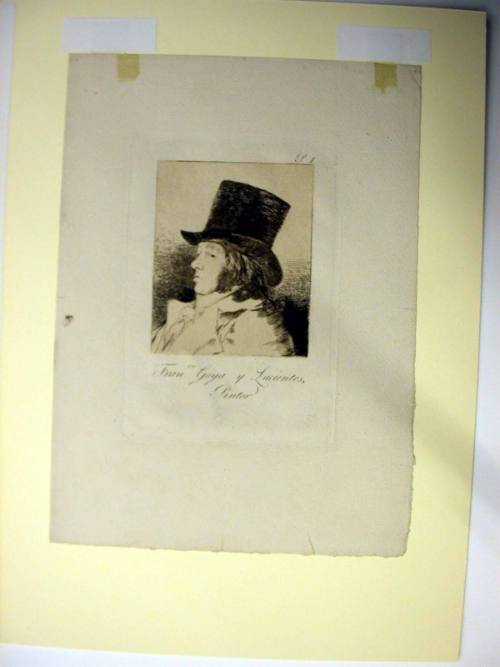

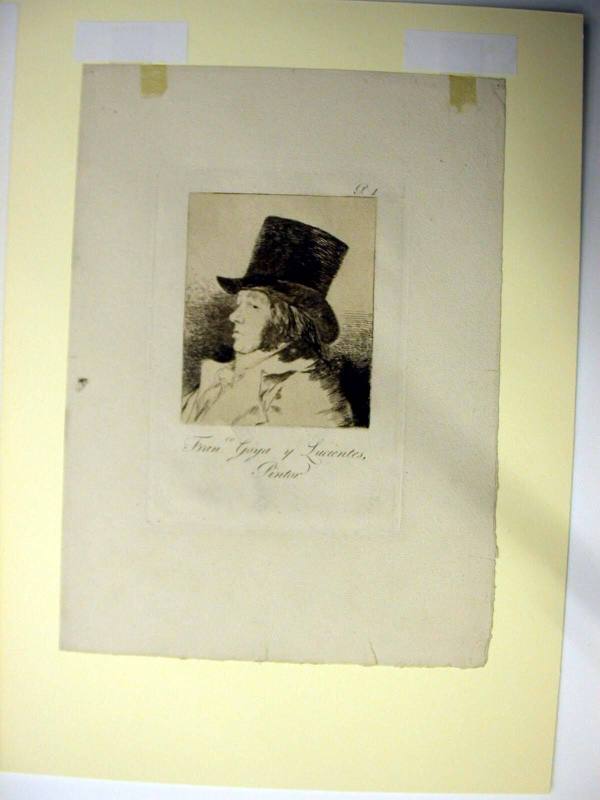

Francisco Jose de Goya y Lucientes

Spanish, 1746 - 1828

(not assigned)Spain, Europe

BiographyBy the age of 12 Goya was already showing a remarkable talent for art and his father, who was a master gilder, sent him to learn drawing in the studio of José Luzán. At the time, Charles III was seeking to give a new impetus to Spanish art and had brought Raffael Mengs and Tiepolo to his court in Madrid. Mengs, who had been appointed chief painter to the king to assist in the execution of royal commissions, was responsible for employing Francisco Bayeu, another of Luzán's pupils, and a man who would play a signficant part in Goya's life.Despite his young age, Goya became embroiled in fights that broke out between members of the different guilds and, possibly for this reason, his parents sent him to Madrid. There, in 1763 and 1766, Goya entered the triennial competition to gain admittance to the Real Academia de San Fernando. Although he was acquainted with Bayeu, who was probably a member of the jury, he was not accepted, although he subsequently found a protector in Floridablanca, one of Charles III's ministers. Goya appears to have led a disorderly life and displayed an irreverent attitude towards religion and the clergy - a characteristic that would remain with him throughout his life. Floridablanca was unable to intercede on his behalf and, in order to divert attention away from himself, Goya joined the cuadrilla (team) of a bullfighter who was leaving Madrid, which initiated his study of the world of bullfighting.

Following various difficulties - real or imaginary - Goya left for Italy between 1770 and 1771. Nothing definite is known of his life during this period abroad but he appears to have enjoyed some success in Parma, receiving second prize at a competition held by the fine arts academy. During his time in Italy, he was introduced to Pope Benedict XIV and painted a portrait of him which is still kept at the Vatican. He is also believed to have fallen in love with a nun and tried to steal her away from her convent - not a prudent thing to do in the papal states - and he was forced to leave Italy in a hurry.

Whatever may have occurred, Goya returned to Spain in 1771 and executed various commissions in Saragossa. Around 1773, he returned to Madrid and settled there, marrying Josefa Bayeu, the sister of his friend Francisco Bayeu. Together they had 20 children, almost all of whom died in infancy. Through the intervention of his brother-in-law, Goya joined the studio of Raffael Mengs and, up to 1792, worked primarily at producing some 43 tapestry cartoons for the workshops of the Santa Bárbara royal tapestry works. During this period Goya discovered the paintings of Velázquez - a discovery that was to change his life - and in 1778, made an engraving of Las Meninas. Also during this period, he was able to familiarise himself with the royal collections, which included works by Van Dyck, Titian, Tintoretto, Raphael, Rubens and Rembrandt. More than anything, Goya wanted to become a court painter and in 1779, he had the honour of being presented to the king, followed in 1780 by his election to the Real Academia de San Fernando. This success was crowned in 1786 when he was finally appointed painter to King Charles III. Goya continued to keep this post in 1788 when Charles IV and Queen Maria Luisa acceded to the throne, and to hone his skills, exploring different techniques and styles widely up to 1792. However, in 1790, he became aware of the persecution suffered by his liberal friends attracted to the ideals of the French Revolution. As both the favourite of the nobility - who wanted him to paint their portraits - and a liberal-thinking friend of the people, Goya faced a dilemma, which he resolved, to some extent, through his contempt for the Inquisition and the skill with which he depicted the spectacles of everyday life held dear by the people.

Despite his attachment to the Spanish court, Goya did not conceal his sympathy for the French Revolution, but his presence there was eventually compromised by romantic adventures involving various noblewomen and he was obliged to withdraw from the court for a year. In 1792, Goya was in Cádiz, staying at the home of his friend Don Sebastián Martínez whose portrait he painted. On his way back to Madrid he was taken ill: he began to lose his balance, to have hallucinations and was plagued by terrible noises in his head. He survived but was left almost completely deaf.

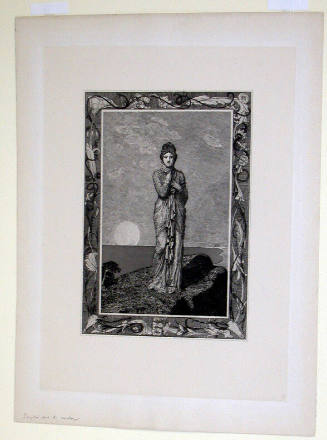

In 1795, Goya's interest in the Duchess of Alba extended beyond the simply artistic and, when the Duke of Alba died in 1796, she withdrew to Andalusia, where Goya joined her, returning in 1797 to Madrid where, in 1799, he was again appointed chief court painter. In 1802, the Duchess of Alba died, which affected him badly, leading to a decline in his creative output. Not long after began the turmoil that would involve the whole country, beginning with Napoleon's invasion in 1808, followed by the national uprising and the collapse of the royal dynasty. Napoleon took advantage of the disagreement between King Charles IV and his son Ferdinand, who had been brought to the throne by popular support, to impose Joseph Bonaparte on the throne of Spain. Goya retained his post as chief painter to the court, but aware of the political destitution and the horrors of the war, he found himself pulled between the liberal ideas of the French and opposition to their occupation of his country. Though perhaps lacking conviction, Goya continued to produce portraits of the monarchs and occupants of high positions in a succession of different courts, beginning with the court of Charles III, followed in 1789 by that of Charles IV and the favourite Godoy. In 1808, he painted the Portrait of Ferdinand VII, but following the events of May that year, he was required to serve Joseph Bonaparte who, along with many Spanish intellectuals, Goya saw as the embodiment of the ideals of the French Revolution. In 1812, the year of his wife's death, he painted the Portrait of Wellington, who entered Madrid in August; with the restoration of Ferdinand VII by the allies in 1814, he resumed his position at court.

Following the restoration of the monarchy, Goya became exposed to persecution from reactionaries and he began increasingly to withdraw, buying a house at Carabanchel on the outskirts of Madrid, known as the 'Quinta del Sordo' or 'House of the Deaf Man', where he lived away from other people. However, many liberals were pursued and Ferdinand VII is believed to have brought Goya before the Inquisition. In 1823, he asked to be relieved of his duties and left for Bordeaux, then for Paris, where - not speaking French and almost completely deaf - he mixed mainly with Spanish friends. In 1826, he went back to Madrid to settle his affairs before returning to Bordeaux, where he eventually died. Goya was buried in Bordeaux, but his body was later moved to Madrid and his tomb now stands in the centre of the Ermita de S Antonio de la Florida, which he himself had decorated.

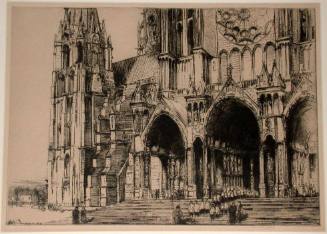

When Goya returned to Saragossa from Italy, the unruliness of his youth now behind him, he was commissioned to paint a Gloria to decorate the small choir of the cathedral of Nuestra Señora del Pilar, completed in 1772, together with paintings for the Sobredial and the church of Remolinos, and part of the decorations celebrating the life of the Virgin for the Aula Dei charterhouse near Saragossa. These reveal his confidence in fresco technique that he had probably learned in Italy. During his first period in Madrid, Goya remained very open to the various artistic trends of the time, from the Baroque of Antonio Martínez - whose work he had seen at the Aula Dei charterhouse - to the academic style of Bayeu and the Rococo approach of the German artist Mengs. In the circles in which he moved, Mengs was the acknowledged master, and it was Mengs who was responsible for reviving the art of tapestry in Spain, depicting spirited scenes populated by Spanish people in contemporary costumes. Mengs commissioned Goya to produce a series of cartoons for the tapestry works which won him favour at court.

Goya's letters to his childhood friend Zapater reveal that he embarked on this lengthy project - which continued from 1775 to 1792 - with an almost childlike enthusiasm. The ambiguous nature of Goya's personality is already apparent in these works: alongside charming 18th-century scenes with attractive compositions and lively colour - such as The Picnic (1776), The Florida Ball (1777), The Parasol (1778) and The Swing (1779)- are some which foreshadow his later hallucinatory paintings. By 1779, in The Crockery Vendor, we see the harsh features of an old woman's face, which forms a sharp contrast with the light and delicate treatment of the young girls seated around her. In the Seasons, the second series which he produced for the King's son, we see the artist's concern with the difficult life of the Spanish people, such as Winter, which shows a poor woman going to the fountain with her children, numb with cold. In the final series, which includes The Manikin (1791) and Blind Man's Buff, Goya displays the full extent of his skills based on the life of Madrid, which provided him with a rich repertoire of subjects.

In 1780, Goya returned to Saragossa to work with Bayeu on a series of frescoes for the cathedral devoted to the Virgin, known as Regina Martyrum, as well as other religious works for churches in Madrid, Valencia and Valladolid. Although lacking in religious fervour, these paintings demonstrate Goya's technical expertise, his sense of the dramatic and his gifts as a colourist. During the same period, he also worked as a portraitist, producing many portraits of the royal family and aristocracy as well as paintings of children, such as his 1787 painting of Don Manuel Osorio de Zúñiga, which are notable for their tenderness. In 1783, he produced Portrait of Minister Floridablanca and The Infante Don Luis and his Family; in 1786, Portrait of Charles III in Riding Dress, the first of his royal portraits; and around 1786, The Marquesa de Pontejos. In 1788, he painted Portrait of the Conde de Cabarrus, and in 1789, The Duke of Osuna with his Family. In his portraiture Goya always sought to convey the personality of the model, however unfavourable, combined with economy of means, rejecting backdrops in favour of neutral backgrounds that focused attention on the subject - a technique later adopted by Manet.

In 1792, following the illness that left him deaf, and in partial disgrace at court, Goya withdrew into himself. Having painted the superficial aspects of the world around him, he now turned to the other side of life, opening his mind to the hallucinations that would come to haunt him. By 1793, he had begun work on 11 pieces that he described as 'cabinet paintings', which he offered to Don Iriarte, vice patron of the Real Academia de San Fernando: 'I set to work on a group of cabinet paintings in which I managed to include the kind of observation that is usually absent from commissioned works where there is no room to develop caprice and invention.' This sentence marks a watershed between the two main periods and different natures of Goya's work - a liberation, or revolt even, from the scenes of entertainments and commissions for religious subjects, which he expressed in series of new themes: The Burial of the Sardine, The Flagellants' Procession, Village Bullfight, Tribunal of the Inquisition and The Madhouse. Just as these subjects delve into the darker, more grotesque side of Spanish life, so too there is a change in his style of execution, which becomes more violent, characterised by broader brushstrokes and an unevenness of line and accent. His use of colour also becomes darker, punctuated by just a few strident highlights in chiaroscuro. Alhough his official portraits remained largely unaffected by this new style, it came to characterise the paintings, engravings and drawings of the second and final part of Goya's career.

Etchings and aquatints published from 1799 onwards display the same caustic and ferocious vigour. In Los Caprichos, a series of 88 plates produced between 1797 and 1799, Goya castigates all the absurdities, vices and intolerance of the time and, by extension, those of humanity in general, including the ruin caused by drunkenness. Baudelaire described one of most famous of the Caprichos, entitled The Dream of Reason Produces Monsters as 'this nightmare full of unknown things' where the monsters, the representations of the demons of religion, were all the more perturbing because they were 'born viable and harmonious'. Malraux also comments on the new dimension the Caprichos bring: 'The Caprichos certainly have depth. But it is not the depth of reality. It is not the depth of the Italians. It is the depth of illumination. And the illumination Goya brings does not aim to create a space. As with Rembrandt or the cinema, it aims to connect what it separates out from the darkness to a meaning that goes beyond it; that transcends it, in fact. Night is not only black, it is also night.'

In an entirely different vein, Goya also continued to work as a portraitist. Portraits painted between 1794 and 1795 include The Marquesa de la Solana, now in the Louvre, The Duke of Alba Playing the Harpsichord, the posthumous Portrait of Francisco Bayeu in 1795, the year of Bayeu's death, his face marked by suffering, and his first portrait of the Duchess of Alba, who, it has often been claimed (though with little evidence), was the model for Goya's later paintings of the Naked Maja and the Clothed Maja.

In 1797, Goya returned to Madrid and worked relentlessly, finishing the Caprichos and, in 1798, starting work on the fresco decoration of S Antonio de la Florida, commissioned by Charles IV, which remains one of Goya's most important works. Goya brings the scene up to date by portraying the figures in contemporary dress. The diversity of expression and vivacity of his execution, marked by broad, sweeping brushstrokes, give the work a 19th-century flavour, although the composition with its circular balustrade is reminiscent of Mantegna or Tiepolo. At about the same time, Goya painted a Last Supper for the Sta Cueva church in Cádiz, and in 1798, an altarpiece, Judas' Betrayal or the Arrest of Christ, for the sacristy of Toledo Cathedral, the delicate execution of which contrasts strongly with the decoration of S Antonio. Between 1797 and 1800, Goya painted scenes of witchcraft, such as The Forcibly Bewitched (El Hechizado por Fuerza), The Witches' Sabbath, the spirit of which remains related to his first cabinet paintings, and the Caprichos, while continuing to paint portraits in accordance with his position as court painter. These include: the minister Gaspar Melchor de Jovellanos (1798), the French ambassador Guillemardet (1798), La Tirana (1799), Queen Maria Luisa in a Black Mantilla (1799) and Queen Maria Luisa in Court Dress (1800). It is thought that the two paintings of the Majas coincided with these court portraits of 1798 to 1800 and that they were commissioned by Godoy, perhaps as a distraction from his relationship with the queen.

In 1800, Goya managed to assemble the entire family of Charles IV - fourteen people - for a large family portrait. The complexity of the staging, the magnificence of the pomp and the skill Goya employs to magnify the attitude and posture of his royal models, while still bringing a certain domestic bonhomie to the gathering, diverts the focus away from their faces, although he still portrays the vacant features of the king and the brutishness of the queen with great ferocity; even the second prince is treated insidiously as a caricature of Godoy - only the children are more or less spared. In his individual portraits, Goya was often pitiless, depicting his subjects without restraint and showing how aspects such as heredity had made them degenerate over the course of successive generations. His clients, however, even those who found least favour, such as Queen Maria Luisa, whom nature had treated far from kindly, declared themselves delighted by his work and showed her satisfaction by making him a very generous gift of 12,000 reals. But there were also exceptions: in Goya's portrait of the Countess of Chinchón (1800), executed with great feeling, the countess - the scorned wife of Godoy - symbolises virtue in the midst of a court riddled with corruption. Godoy himself was also painted by Goya in 1801.

By the beginning of the 19th century, Goya had adopted a new way of working, often abandoning his brushes and seizing upon the first thing that came to hand - a sponge maybe or a piece of cloth - to apply colour to the canvas, then spreading it with his thumb. Goya said: 'I have had three masters: Nature, Velázquez and Rembrandt'. He also said, 'Colours do not exist in nature, there is only shade and light. Give me some charcoal and I will make your portrait.' Works from this period include: The Count and Countess of Fernán Nuñez (1803); The Marquesa de Villafranca (1804); the Man in Grey (1805-1806), who was his son Javier; Doña Isabel Cobos de Porcel and Isidoro Maiquez (1807). Around 1806, he also painted - again using this technique of rapid execution - scenes showing the Capture of the Bandit Maragato by the Monk Pedro de Zaldivia.

Between 1810 and 1814, Goya drew and engraved the series The Disasters of War, which, with an unprecedented ferocity, depict atrocities - imagined or witnessed - perpetrated by Napoleon's army: the summary executions, burning, pillaging and massacres. Other works, such as the Plague Hospital, capture the stifling atmosphere of disease through the use of backlighting. As Malraux puts it, 'A dense background envelops the figures instead of highlighting them'. It was in 1814 that he painted the two famous works known as Second of May (Dos de Mayo)- showing the savage charge of the Mamelukes against the insurgents at the Puerta del Sol - and Third of May (Tres de Mayo) portraying an execution. Around 1810 to 1814, without any apparent connection of theme, Goya painted Majas on the Balcony, a scene reminiscent of happier times, the delightful and carefree The Young Girls or The Letter and Time and the Old Women. He also executed The Board of the Philippines Company (1815-1818) at Castres museum, representing a ghostly gathering of the company's leaders. His Self-portrait of 1815-1816, on the other hand, expresses all the bitterness and disappointment the artist felt in old age.

Although he continued to paint portraits, Goya received fewer and fewer commissions as society grew suspicious of him. Between 1816 and 1820, he engraved Tauromachy, a set of 33 plates on the ritual of the bullfight, and in 1819, the series known as Los Disparates (The Follies). The titles he gave to these, such as Extravagances and Absurdities, describe what are often strange, indecipherable visions, wild hybrid forms somewhere between the human and the animal, inspired by the numerous sketches Goya had jotted down in notebooks throughout his life. There were more than a thousand of these, observed from nature or born of his imagination. Malraux's comments on the Caprichos, in particular regarding the dramatic opposition of large areas of light and shade, also apply to this series of engravings, which form a poignant and very modern group of work; their message and the execution and skill of the drawing, exceptional in both content and form, continue in the tradition of Rembrandt's engravings and were referenced in the work of Picasso.

Following his withdrawal to the Quinta del Sordo, Goya now began to paint in a different register - that of horror. This can be seen in such works as The Fire and The Shipwreck, and, above all, on the walls of his house, which display the wild, sweeping brushstrokes of the celebrated 'black paintings' of 1818-1823. The deep, mysterious and frightening black tones are pierced by violent splashes of white, yellow and red. They also include the gory painting of Saturn Devouring One of his Children; The Fates; Judith and Holofernes; the witchcraft scenes of The Pilgrimage of St Isidore and The Great He-Goat. After Goya's return from Paris and Madrid, he painted one final portrait, The Dairymaid of Bordeaux, a kind of street scene executed with rapid brushstrokes that foreshadow Impressionism; in this, as in some distant memory, Goya rediscovers, at the age of 82, the limpid atmosphere and light blue tones of the Madrid tapestries of earlier and happier days.

Throughout his life, Goya produced two different kinds of work, a duality that is always present. On the one hand there were the commissions: the decorative works and portraits; on the other, were the works he created for himself: the reflections of his thoughts and observations on the life and history of Spain and her people.

Goya's influence was considerable, not only in Spain where it hastened the awakening of the Spanish genius for art, but also in France. Delacroix said that it was seeing a painting by Goya that had awakened in him his vocation as a painter. We know too that Goya was Manet's greatest influence and that Manet took direct inspiration from him in works such as The Balcony and The Execution of Maximilian. As painters, Delacroix and Manet were both affected as much by the novelty and boldness of his technique as by the power of his images.

"GOYA Y LUCIENTES, Francisco José de." In Benezit Dictionary of Artists. Oxford Art Online, http://www.oxfordartonline.com.proxy.lib.fsu.edu/subscriber/article/benezit/B00077584 (accessed April 16, 2012).

Person TypeIndividual

Italian, 1692 - 1770