Corrado Giaquinto

Italian, c. 1694 - 1765

(not assigned)Italy, Europe

BiographyBorn Molfetta, nr Bari, 8 Feb 1703; died Naples, 18 April 1766.Italian painter. He was a leading exponent of the Rococo school that flourished in Rome during the first half of the 18th century.

1. Life and work.

(i) Molfetta and Naples, 1703–27.

Giaquinto began his training in the studio of Saverio Porto (c. 1667–c. 1725), a provincial painter in Molfetta. In March 1721 he left for Naples, where, except for a brief return to Molfetta (Feb 1723–Oct 1724), he lived for the next six years. According to De Dominici (1745), Giaquinto’s earliest biographer, once in Naples the artist entered the studio of Nicola Maria Rossi, a follower of Francesco Solimena. While Solimena’s monumental and complex style influenced Giaquinto throughout his career, there is no documentary evidence to suggest that Giaquinto entered Solimena’s flourishing studio. However, close contact between Solimena and Giaquinto during these formative years is indicated by several autograph paintings modelled after the master’s work. Giaquinto’s Visitation (Naples, Pucci priv. col.) appears to have been copied from Solimena’s altarpiece of the same subject for S Maria Donnalbina. Other early studies after Solimena include Europe, Asia and America (Rome, priv. col., see Bologna (1979), p. 61) and the Archangel Michael (Rome, Vatican Pin.). Equally important to the development of Giaquinto’s mature style were the luminous fresco decorations that Luca Giordano painted for the Certosa di S Martino, Naples, in 1704.

(ii) Rome and Turin, 1727–40.

In March 1727 Giaquinto left Naples for Rome. During the 1730s he worked as an independent artist, modifying his robust Neapolitan style to reflect the classicizing Rococo taste exemplified in the works of the followers of Carlo Maratti such as Sebastiano Conca. Giaquinto’s reputation was firmly established in 1733, when he completed an extensive fresco cycle in the nave and cupola of the French church of S Nicola dei Lorenesi, Rome. In these frescoes the Baroque stylistic traditions developed by Pietro da Cortona, Maratti and Giordano were masterfully synthesized and updated. The critical success of this commission prompted two invitations to the Savoy court in Turin in June 1733 and c. 1735. Although both visits were brief, his contacts with the works of contemporary artists of the French, Venetian and Neapolitan schools, such as Carle Vanloo, Giovanni Battista Crosato and Francesco De Mura, were important for the perfection of his elegant Rococo forms and pastel palette. Giaquinto’s first major commission in Turin was in 1733, for the frescoes depicting the Triumph of the Gods (destr. World War II), Apollo and Daphne and the Death of Adonis for the Villa della Regina (both in situ). When he returned to Turin c. 1735 he decorated a small chapel dedicated to St Joseph (designed by Filippo Juvarra for the church of S Teresa) with two large oils, the Rest on the Flight into Egypt and the Death of St Joseph, and a vault fresco, St Joseph in Glory. The epitome of Giaquinto’s exquisite Turinese style, however, is found in his Aeneas cycle, a series of six oils which were moved from Turin to their present location in the Palazzo Quirinale, Rome, in the late 19th century. In Rome Giaquinto continued to paint in this sophisticated style, examples of which can be found in the Virtues (c. 1733–5), a small ceiling fresco for the Palazzo Borghese, and the Assumption of the Virgin (1739), an altarpiece commissioned by Cardinal Ottoboni for the church of the Assumption, Rocca di Papa.

(iii) Rome, 1740–53.

The 1740s represent Giaquinto’s most significant decade in Rome. The artist was admitted into the Accademia di S Luca in 1740. Some time thereafter he established a studio and was put in charge of training all the Spanish students sent to the papal city to perfect their craft. Giaquinto’s most important commissions during this decade were his large decorative programmes for the churches of S Giovanni Calabita (c. 1741–2) and Santa Croce in Gerusalemme (c. 1744), which established his international reputation as the leader of the Roman Rococo school. During this period his style moved away from the previous Rococo forms of the 1730s towards a more solid classicism that pays homage to the tradition of the Grand Style as exemplified by Maratti, the last great master of the Roman Baroque. Classicizing tastes were especially strong during the 1740s when Pompeo Batoni and the Frenchman Pierre Subleyras established reputations in Rome. Giaquinto’s mature Roman style is evident in his nave fresco for S Giovanni Calabita, St John of God Healing the Plague Victims, and in his altarpiece for S Maria dell’Orto, the Baptism of Christ (1750). Both examples convey a heightened sense of solemnity, which the artist achieved through the use of simplified compositional arrangements and figure types reminiscent of Maratti shown in postures of quiet repose. Other important commissions included the vault fresco of God the Father Presenting the Tablets to Moses (1743; Rome, S Lorenzo in Damaso, Ruffo chapel) and such large canvases as the Transportation of the Relics of SS Eurychetes and Acutius (1744; Naples Cathedral).

In 1748 Giaquinto and his studio, which included his most successful student, Antonio González Velázquez, were commissioned by Ferdinand VI of Spain to decorate the Trinitarian church of Santa Trinità degli Spagnoli, for which he painted the altarpiece the Holy Trinity Freeing a Captive Slave (1750). The artist’s professional relationship with the Spanish crown was reinforced in 1753 when Giaquinto was summoned to Madrid by Ferdinand VI. In August 1752 the court painter Jacopo Amigoni had died, and a successor was needed to fresco the ceilings of the new Palacio Real.

(iv) Spain, 1753–62.

Giaquinto’s nine-year stay in Spain, where he established himself as Europe’s foremost fresco painter after Giambattista Tiepolo, was the highpoint of his career. His prominence within the artistic hierarchy at the Bourbon court recalled the influence exercised by Charles Lebrun at Versailles. Soon after his arrival at court in June 1753, Giaquinto was appointed to three posts: First Painter to the King, Director of the Academia de S Fernando and Director of the royal tapestry factory of S Barbara, Madrid. His position as Director-in-Chief of the court’s artistic affairs caused Giaquinto’s influence to extend to the next generation of Spanish artists, including Francisco Bayeu and Francisco de Goya. His influence was all the greater because his tenure coincided with the decoration of the new Palacio Real, the most important artistic project of the 18th century in Spain. Here Giaquinto’s role extended far beyond his contribution as a painter: he designed many of the sculptures and stuccos in the areas of the palace where he worked; in addition he had many administrative duties, involving frequent meetings with the Secretary of State and other ministers in charge of the palace works. He was responsible for the well-being of a huge workforce and was often called upon to grant commissions and settle price disputes between court artists and palace administrators. Despite his powerful position, however, he was untyrannical by nature and managed to form a smooth working relationship with the architect Giovanni Battista Sacchetti, the sculptors Giovanni Domenico Olivieri and Felipe de Castro and the painters Antonio González Velázquez and José de Castillo, who worked under him at court.

Giaquinto’s first royal commission (Oct 1753) was to restore Luca Giordano’s fresco of the Institution of the Order of the Golden Fleece in the throne room of the palace of the Buen Retiro, Madrid. The vibrant colours and dazzling brushwork of Giordano’s Spanish frescoes had a decisive effect on Giaquinto, who possessed a similar talent for brilliant pictorial effects. Though not securely dated, his first autograph works in Spain were probably a series of large oil paintings depicting the Old Testament history of Benjamin for the Sala de Conversatión (now the Comedor de Gala) at the palace of Aranjuez, near Madrid. Important works for other royal sites included the Holy Trinity and Saints (c. 1755–60; Valladolid, Mus. N. Escul.), which, along with a series of small oils of the Life of Christ (c. 1755–60; Madrid, Prado; Madrid, Escorial, Casita Príncipe), was commissioned for the private oratories of Ferdinand VI and Barbara of Braganza at the palace of the Buen Retiro. Giaquinto also supervised the decoration of the royal monastery of Las Salesas Reales, Madrid, where his students Antonio and Luis González Velázquez frescoed the cupola of the church (c. 1756). Giaquinto’s own work at Las Salesas was limited to one altarpiece in the church, SS François de Sales and Jeanne de Chantal (completed Oct 1757; in situ).

Stylistically, Giaquinto’s frescoes at the new Palacio Real are his most impressive works. In June 1754 he was asked to paint the vaults above the entrance, choir and presbytery of the royal chapel along with its cupola and pendentives, work that was not carried out until 1758–9. His luminous colours, dynamic brushwork and masterly composition are manifest in the chapel’s cupola, where dramatic groups of figures are interposed with delicate swirls of pastel clouds. Equally impressive are two large vault frescoes, one above the grand staircase of the palace, Spain Rendering Homage to Religion and the Catholic Church (modello, c. 1759; Saragossa, Mus. Prov. B.A.), and the other in the Hall of Columns, the Birth of the Sun and Triumph of Bacchus (c. 1761–Feb 1762).

Shortly after completing the Hall of Columns, Giaquinto was commissioned to fresco the vault in the adjoining Hall of the Halbadiers (Feb 1762), but later the same month he was granted leave of absence to return to Naples for medical treatment. Eventually the task of completing this commission was given to Tiepolo, who had been called to Spain in 1761 by Charles III to fresco the throne room of the new Palacio Real. After Giaquinto left Madrid his artistic and administrative duties at the royal palace, academy and tapestry factory were assumed by Anton Raphael Mengs, who arrived at court in September 1761. It has generally been assumed that the arrival of Tiepolo and Mengs at court denoted Giaquinto’s fall from favour and prompted his swift departure from Madrid in early 1762. However, documentary evidence indicates that Giaquinto intended to return to Spain to resume his duties at court but was prevented from doing so by continued ill-health.

(v) Naples, 1762–6.

Giaquinto remained in Naples until his death in 1766. During this time he retained his position as First Painter to Charles III and continued to work for the Spanish monarchy, establishing a close working relationship with the Royal Architect Luigi Vanvitelli, through whom he was commissioned to execute one in a series of allegorical subjects for a tapestry cycle destined for the Stanza del Belvedere in the royal palace, Naples (Allegory of War, 1763; Caserta, Pal. Reale). His most important commission, however, and his major collaboration with Vanvitelli, was for a large Marian cycle in the sacristy of the royal church of S Luigi di Palazzo (Jan 1764–July 1765). The simplified composition, monumental figures and elegant postures of the S Luigi altarpieces, including the Marriage of the Virgin (Pasadena, CA, Norton Simon Mus.), the Visitation (Montreal, Mus. F.A.), the Purification at the Temple (Cambridge, MA, Fogg) and the Rest on the Flight into Egypt (Detroit, MI, Inst. A.), indicate that during his last years Giaquinto reiterated and amplified his Roman style of the 1740s to suit the developing Neo-classical tastes of the 1760s. With the advent of Neo-classicism, Giaquinto’s reputation plummeted and was not restored until Moschini’s pioneering article (1924) and d’Orsi’s monograph (1958).

2. Working methods and technique.

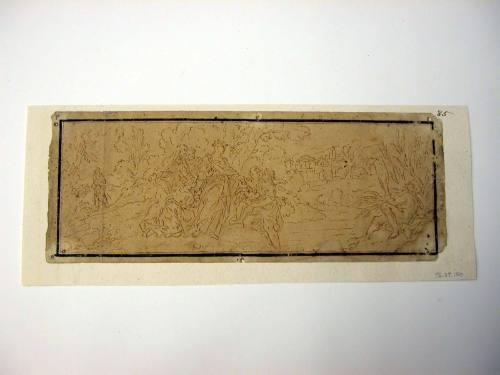

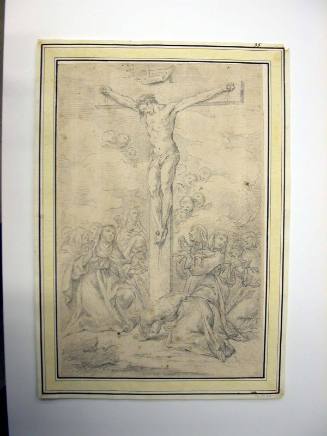

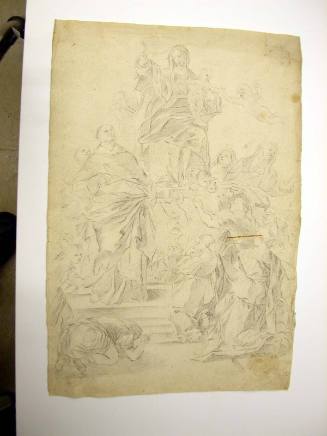

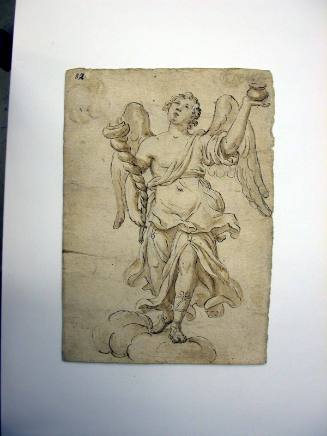

Giaquinto’s artistic talents were evolutionary rather than revolutionary. From the beginning of his career he developed an array of stock figure types and compositional formulae, which he continued to revise and perfect until he achieved a level of exquisite refinement. His preference for familiar pictorial motifs rather than more innovative visual solutions suggests an academic sensibility that belies the spontaneity of conception suggested by his lively preparatory drawings and oil sketches.

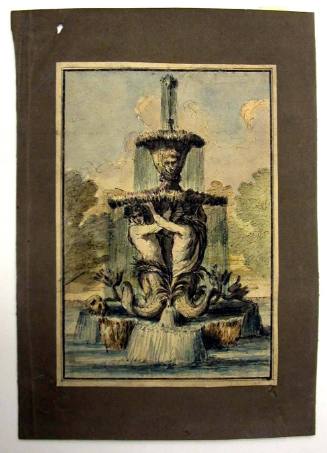

Although Giaquinto was a conscientious artist, he did not make minutely detailed studies that closely anticipate a final work. In his youth he produced the usual academic life studies, executed in oil or in chalk. From early in his career, he used quick schematic chalk drawings to work out the poses and gestures of individual figures, the arrangement of drapery and of figure groups. Studies for large-scale compositions, such as altarpieces and frescoes, were often executed in greater detail in pen and ink. However, his final compositions were seldom fully planned and, significantly, the more finished drawings were not squared for transfer. As he matured as an artist, Giaquinto often worked out his pictorial ideas directly in oil sketches painted on copper or canvas. Starting with a ground of pearly grey, he applied a rich selection of delicate pastel hues such as deep coral, sea green, turquoise, lilac and lemon yellow. The consistency of paint varies from an opaque buttery paste to transparent pigmented glazes; built up consecutively, these result in a luxuriant surface that seems to shimmer with silvery light. Although rapidly executed, Giaquinto’s brushstrokes are always precisely controlled. The sumptuous texture of his oil sketches is modified in his large-scale canvases, where the colours tend to be deeper and the surface treatment smoother. However, the lighter pastel coloration, luminosity and rapid brushwork of the artist’s oil sketches are apparent in his dynamic fresco technique, which reached an apex of sophistication and refinement in the cycles painted on the large vaults of the New Royal Palace in Madrid.

A true assessment of Giaquinto’s oeuvre and his working methods and technique has been obscured by the existence of a large number of drawings, oil sketches and modelli executed in his style by his Italian and Spanish followers. The problem is complicated by Giaquinto’s tendency to reuse his own established figure types and compositional formulae and occasionally to produce replicas of his own paintings. Other problems of authenticity arise from the lack of information about the organization of his Roman studio and about the numerous lesser-known artists who worked under him in Spain; the hands of distant followers in Naples and Sicily who worked in a similar manner, into the early 19th century also need to be identified. The precise relationship of studio replicas and close adaptations to Giaquinto’s autograph paintings can only be judged on the basis of handling and quality: these criteria show that the majority were executed by pupils and followers who failed to achieve the precision of the master’s brushwork or the subtlety of his pastel colours.

Irene Cioffi. "Giaquinto, Corrado." In Grove Art Online. Oxford Art Online, http://www.oxfordartonline.com.proxy.lib.fsu.edu/subscriber/article/grove/art/T032087 (accessed April 10, 2012).

Person TypeIndividual