Tommaso Minardi

Italian, 1787 - 1871

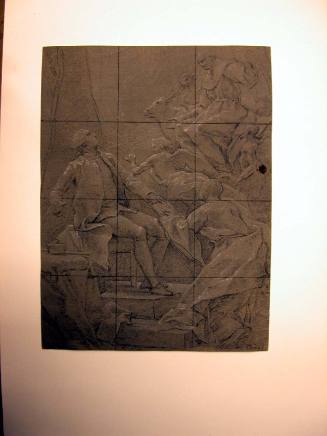

Italian painter, draughtsman, teacher and theorist. He studied drawing with the engraver Giuseppe Zauli (1763–1822) who imbued Minardi with his enthusiasm for 15th-century Italian art and introduced him to his large collection of engravings after the work of Flemish artists such as Adriaen van Ostade. However, Minardi was strongly influenced by the Neo-classical painter Felice Giani, who ran a large workshop in Faenza, and whose frescoes of mythological scenes (1804–5) at the Palazzo Milzetti he saw being painted. In 1803 he went to Rome on an annual stipend provided by Count Virgilio Cavina of Faenza (1731–1808), and he received (1803–8) additional financial assistance from the Congregazione di S Gregorio. He was given the use of Giani’s studio and through him met Vincenzo Camuccini who, with Canova, dominated the artistic establishment in Rome at that time. Although Minardi learnt the precepts of Neo-classicism from Camuccini, he did not share his interest in heroic art. His first works done in Rome show his interest in the theme of master and acolyte. In Socrates and Alcibiades (1807; Faenza, Pin. Com.), for example, he has included himself among a group of elderly philosophers and young students who are placed on either side of a portrait bust of Zauli. He sent this drawing to his patrons, the Congregazione di S Gregorio, no doubt to reassure them of his aptitude and moral correctness. Supper at Emmaus (c. 1807; Faenza, Pin. Com.) was another painting destined for the same patrons. The confined pictorial space, with a single source of light entering through a small window, and the casual poses of the figures are reminiscent of Flemish art and of the works of the northern Caravaggisti, familiar to the artist through engravings. From 1808 to 1813 he had an alunnato from the Accademia di Belle Arti in Bologna and sent back the painting Diogenes (1813; Bologna, Pin. N.), which is unusual both in its bold design and large size (1340×987 mm).

In his Self-portrait, convincingly dated to 1813 (Piperno, pp. 175–6), Minardi created a crystalline, austere atmosphere. Light entering from two windows reveals a humble interior and a sombre occupant. Minardi’s early contact with the Nazarenes, who were in Rome from 1810, served to increase his preference for the aesthetic and spiritual qualities of early 15th-century art. In 1812 he received a commission from the Milanese printmaker and writer Giuseppe Longhi to execute a detailed drawing (Rome, Vatican, Bib. Apostolica) of Michelangelo’s Last Judgement (1535–41; Rome, Vatican, Sistine Chapel). This project was to occupy him for 13 years but was never published. His close study of Michelangelo’s work, for which he produced over 40 related drawings (Rome, G.N.A. Mod.), also became an excuse for self-doubt as a painter. He wrote in his unpublished autobiography that ‘from then I lived in a state of complete isolation and squalor’. On account of this ‘inability’ to paint, in 1817 he refused a commission from Camillo Massimo to decorate his casino, Villa Massimo Lancelotti, and the work was given instead to several Nazarene painters, much to Minardi’s regret.

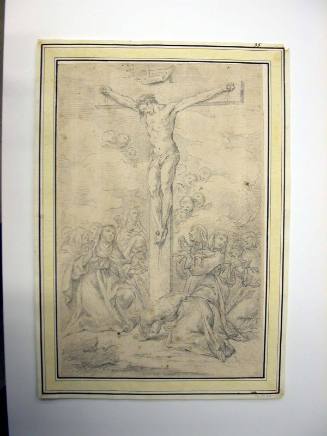

In 1818 Canova proposed Minardi as Director of the Accademia di Belle Arti in Perugia, a post that he held from 1819 to 1821. In 1821, on the strength of his merits as a draughtsman, students at the Accademia di S Luca in Rome put his name forward for the directorship. Even though he was endorsed by both Canova and Pope Pius VII, this was insufficient to sway members of the Accademia in his favour. He was, however, created Professor of Drawing there in 1822, a position he held until 1858. From this time his drawing technique became increasingly linear, and his subjects almost entirely religious, except for several themes derived from Dante. The Angel of the Apocalypse (1824; Faenza, Pin. Com.) is a perfect expression of the ideals of Purismo and recalls John Flaxman’s style as does the sombre Soul of the Shepherd’s Baby (c. 1825; Forlì, Bib. Com. Saffi).

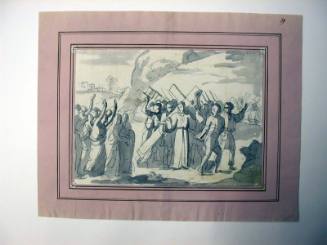

At the Accademia Minardi opposed the formal and rational theories propounded by academic artists and, together with Friedrich Overbeck, he dominated religious art in Rome until about 1850. A decisive influence on both of these men was the presence of Ingres in Rome from 1834 to 1841 as Director of the Académie de France. In 1834 Minardi gave a controversial lecture (‘Delle qualità essenziali della pittura italiana …’) at the Accademia in which he questioned the basis of academic painting. He rejected the need to make a slavish study of ancient sculpture and the works of Raphael, although he recognized the latter’s ‘divine’ quality. Geniuses, he felt, were always the cause of decadence in art. Instead, he placed greater emphasis on the spiritual perception of nature as opposed to the replication of real things; for him, a return to the essentials of Giotto’s art was desirable. The leading exponent of Purismo in Rome, he contributed to the manifesto Del purismo nelle arti, which he, Overbeck, Pietro Tenerani and Antonio Bianchini co-signed in 1843. Among his religious paintings of this period is the Virgin of the Rosary (1840; Rome, G.N.A. Mod.), which is strongly reminiscent of Perugino’s work. By the 1840s his pupils were carrying out his designs, and many of his later works (e.g. Missions of the Apostles, 1864; Rome, Pal. Quirinale) are monotonous and sterile in composition. This decline in powers indicates that, although he had an enormous influence on painters of religious subjects, he was unable to sustain his own theories in practice. Among his many followers were Constantino Brumidi, Antonio Ciseri, Francesco Coghetti and Guglielmo De Sanctis, who wrote Minardi’s biography.

"Minardi, Tommaso." In Grove Art Online. Oxford Art Online, http://www.oxfordartonline.com.proxy.lib.fsu.edu/subscriber/article/grove/art/T058345 (accessed April 11, 2012).

Person TypeIndividual

Italian, c. 1510 - 1561