Paulus Potter

Dutch, 1625 - 1654

Son of Pieter Potter. He was related through his mother, Aechtie Pouwels (d 1636), to the wealthy and powerful von Egmont and Semeyns families, who held important offices in Enkhuizen and at the court in The Hague. He worked in his father’s studio in Amsterdam during the 1630s and, like him, painted history subjects that show the strong influence of Claes Moeyaert, with whom Paulus may also have studied. In the painting Abraham Returning from Canaan (1642; Boston, priv. col., see Romanov, 1934, fig.) he adapted the landscape setting from an etching by Moses van Uyttenbroeck (b. 56) and the figures from works by Moeyaert from over ten years earlier. Significantly, however, he redistributed the numerous animals and figures that Moeyaert had aligned evenly across the frontal plane; Potter placed them to one side, permitting a view into the deep distance where other animals can be seen. Potter followed his father more than Moeyaert in searching for ways to integrate his figures with the landscape, suggesting space by carefully positioning the forms of the figures.

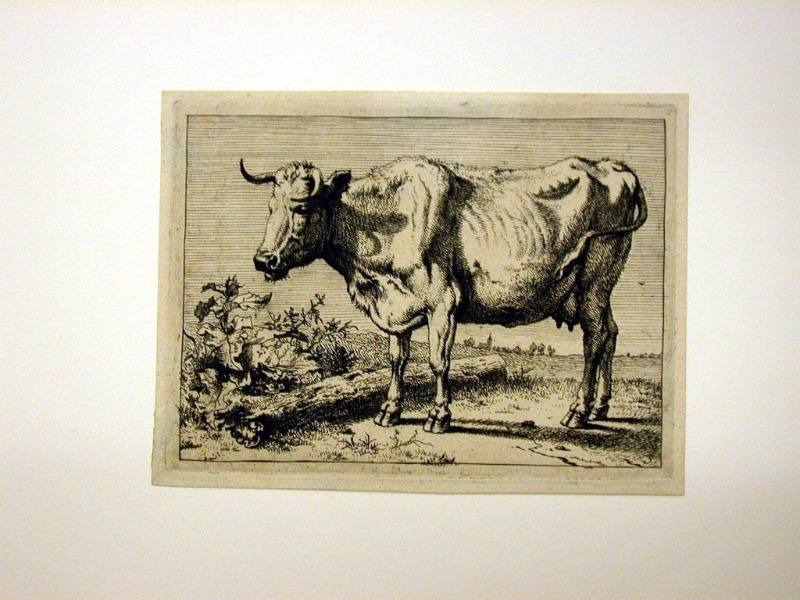

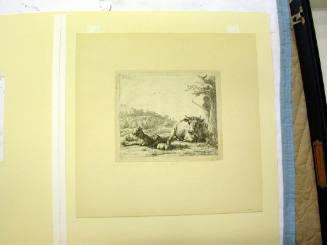

In May 1641 ‘P. Potter’ is recorded as a student of painting in a notebook of Jacob de Wet, another history painter who had contributed to the decorations for the ceremonial entry of Henrietta Maria into Amsterdam in 1641. Paulus may have returned to Haarlem with de Wet, for in the following years his work shows the influence of de Wet’s integrated compositions and of the monumental and realistic naturalism of the works of Gerrit Claesz. Bleker ( fl 1625–56) and especially Pieter van Laer. Potter was probably attracted initially to Bleker’s history paintings, with their ribbons of animals winding into the distance, but was more strongly influenced by his prints. The composition, characterization of the animals and the technique in Potter’s related etchings, the Cowherd (1643; b. 14) and the Shepherd (1644; b. 15), reflect the direct influence of Bleker’s own etchings of rustic shepherds and domestic animals (1638; b. 7–8). Potter’s painting The Milkmaid (1643; Paris, Fond. Custodia, Inst. Néer.) expresses a similar concern for the realistic structure and texture of the animals, which help to define the compositional space. His detailed description of the flowers, butterflies and insects as well as of Dutch farming practices documents his careful observation of reality.

By the mid-1640s Potter had turned almost exclusively from historical narratives to depictions of animals in carefully arranged, flat landscapes and scenes of animals and farmers in the farmyard. The paintings and popular etching series of domestic animals (1636; Hollstein, x, nos 1–14) by van Laer, who had recently returned from Italy, appealed to Potter for the way in which van Laer manipulated forms to define space. Under this influence Potter’s animals increased in monumentality, and his compositions increased in clarity. In his mature paintings, such as Cattle Going out to the Fields in the Morning (1647; Salzburg, Residenzgal.), he, like van Laer, arranged animals at strategic points in the composition to lead the viewer’s eye through a doorway, into the distance or over a hill. This painting also demonstrates Potter’s fascination and facility for rendering the different qualities of direct and reflected light. A similar concern is found in Mercury and Argus (1642; London, V&A), a small pencil drawing on parchment—one of c. ten known compositional drawings by Potter in this medium. Leaving the light edges of faces, legs and leaves undescribed or barely sketched in, he accented the dark shadows with crisp lines, often paralleled by a negative ‘line’ of light to suggest reflection and give the forms fuller three-dimensional definition. With a similar sensitivity, in the Salzburg painting, Potter recorded the way light reflects off the ground on to the underbelly of a cow, glows through its translucent ears and follows the brim of the farmer’s hat, while a gentle morning light fills the air.

Potter’s mature paintings from the late 1640s are also characterized by their rustic naturalism. By describing the farmers and animals in realistic detail, defining the manure caked on the sides of the cattle or the dirt under the farmer’s nails and on his clothes, he emphasized the close connection of his subjects to the earth. As in contemporaneous literature, Potter portrayed the farmer and his animals in a positive light. His women are nursing mothers or milkmaids, his farmers caretakers of animals rather than tillers of the soil. On 6 August 1646 Potter joined the Guild of St Luke in Delft, but he may actually have been living in The Hague, where his parents were. His painting of 1647, the Young Bull (The Hague, Mauritshuis), has become famous for the extremely realistic rendering of the animals; the life-size painting includes a background view of Rijswijk, a village situated between Delft and The Hague. (The work created a sensation when it was exhibited at the Musée du Louvre in 1795, and for the next 100 years critics hotly debated the aesthetic merits and propriety of painting on such a large scale with such detail.) The Bear Hunt (The Hague, Schilderijenzaal Prins Willem V) is another example of Potter’s monumental images. In 1649 he entered the Guild of St Luke at The Hague and the following year married Adriaena van Balckeneynde, the daughter of his neighbour, the court architect Claes Dircksz. van Balckeneynde (d 1664). From 1649 to 1652 Potter lived in the house of the painter Jan van Goyen.

Potter apparently enjoyed sophisticated patronage in The Hague, where, in the late 1640s, his paintings display a more elegant style and subject-matter. In a number of them, such as the Great Farm (1649; St Petersburg, Hermitage) and the Reflected Cow (1648; The Hague, Mauritshuis), he depicted elegant couples visiting the countryside within sight of the city and country houses to swim or simply to enjoy the sights and sounds of nature. Around 1650 he began to include horses in his paintings, such as the elegant Hunting Party (1653; Woburn Abbey, Beds). According to Houbraken, he painted the Great Farm, which he called Het pissende koetje (‘the pissing cow’), for Amalia von Solms, who rejected it on account of the offending cow. Houbraken also noted that Potter was often visited by John Maurice of Nassau, and that Dr Nicolaes Tulp (Rembrandt’s former patron) persuaded Potter to leave The Hague for Amsterdam. Potter’s personal and family connections in The Hague (a cousin, who was counsellor to Prince William II of Orange Nassau, and Willem Piso, a family friend who was personal physician to John Maurice) probably would have given him an entrée into this circle. This is supported, though somewhat confused, by the fact that the large equestrian portrait of Dirk Tulp (1653; Amsterdam, Col. Six), the son of Nicolaes Tulp, was originally a portrait of John Maurice, whose castle at Cleve is visible between the horse’s legs; only after Potter’s death was it changed to represent Tulp.

By May 1652 Potter had resettled in Amsterdam, where he died aged only 29; a portrait of him (1654; The Hague, Mauritshuis) painted shortly before his death by Bartholomeus van der Helst presents him as an elegant gentleman seated before his easel. The works of Karel Dujardin and Adriaen van de Velde, among others, reveal the influence of his small paintings of animals in landscapes or farmyards, while Albert Klomp (c. 1618–88) was a notable imitator of his style.

Potter’s drawings include proficient studies of animals in black chalk (e.g. Three Cows and a Donkey, London, BM; Standing Sow, Paris, Louvre) and pen and ink (e.g. Swineherd with Pigs, Chantilly, Mus. Condé). There are c. 20 etchings of cattle (b. 1–8, 14, 16–17) and horses (b. 10–13), as well as prints after Potter by Marcus de Bije (1639–c. 1690), himself a prolific etcher of animal subjects.

Amy L. Walsh. "Potter (i)." In Grove Art Online. Oxford Art Online, http://www.oxfordartonline.com.proxy.lib.fsu.edu/subscriber/article/grove/art/T069032pg2 (accessed May 8, 2012).

Person TypeIndividual