Augustin Hirschvogel

German, 1503 - 1553

Glass painter, etcher, cartographer and mathematician, son of Veit Hirschvogel the elder. He trained as a stained-glass painter in his father’s workshop and remained there until his father’s death in 1525. In that year Nuremberg accepted the Reformation, spelling the end of monumental stained-glass commissions. This must have profoundly reduced the production of the workshop, now run by his elder brother Veit, and may have forced Augustin to become more versatile. By 1530 he had established his own workshop but in 1531 formed a partnership with the Nuremberg potters Hanns Nickel ( fl c. 1530) and Oswald Reinhart ( fl c. 1530), presumably to share their kiln. This partnership, coupled with Johann Neudörfer’s confusing comments about Hirschvogel in his Nachrichten (1547), formerly led to speculation about his having made a ceramic stove and pots in a classicizing Italianate style. It is more likely that the vessels made by Augustin and described in documents as in a Venetian style were glass, not earthenware.

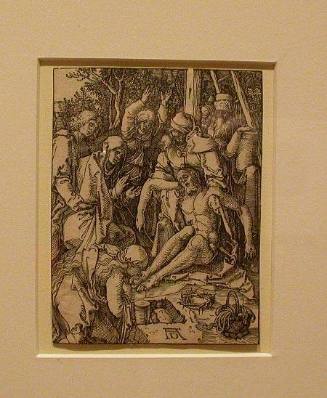

Over 60 pen-and-ink drawings and several stained-glass panels by Hirschvogel survive from his early Nuremberg period (until 1536). The 53 hunting scenes in the Museum of Fine Arts, Budapest, for an extensive series of stained-glass roundels, demonstrate that he was an able and independent draughtsman, well-schooled in Dürer’s drawing style. His drawings most closely resemble those of his contemporaries, the Nuremberg Little Masters such as Sebald Beham and Georg Pencz. Several stained-glass panels, including two roundels from the hunt series and a group of three rectangular panels of angels holding coats of arms from the parsonage of the Sebalduskirche (1520s), show Augustin’s modification of his father’s linear style of glass painting to achieve more tonal, painterly effects. No evidence remains of his documented simultaneous activity of carving armorials.

In 1536 Augustin left Nuremberg for Ljubljana (Laibach) and did not return until 1543. The original purpose for his journey is unknown. His maps of Turkish borders (1539) and of Austria (1542, for Ferdinand I), however, document his earliest known activities as cartographer. He also made etchings during this period, to which he referred in his preface to Geometria (pubd Nuremberg, 1543), a book containing 37 etchings of geometric and perspectival constructions. Commissions for armorials for Franz Igelshofer and Christoph Khevenhüller (1503–57) indicate that by 1543 he had already established contacts with members of the imperial court in Vienna.

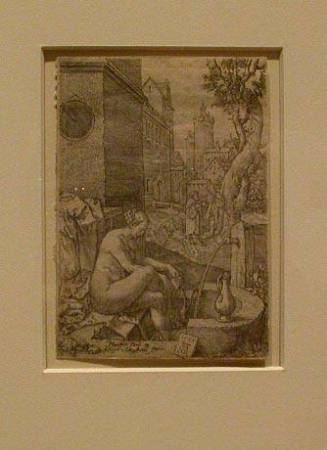

In 1544 Hirschvogel moved to Vienna, where he was engaged as a cartographer, mathematician, etcher and stained-glass painter by an expanded patronage of the city, court and private citizens. The motto ‘Spero fortunae regressum’ (I hope for a return of fortune), found on two self-portrait etchings from 1548, suggests hard times and his aspirations for greater success in the imperial capital. In 1547 the city employed him to make a design for new bastions as well as two etched views and a plan of Vienna (Vienna, Hist. Mus.). His views of Vienna were the first ever done according to scale, and the circular plan was the first ever made by triangulation, a trigonometric system of surveying which Hirschvogel himself developed. The city council sent him to King Ferdinand I in Prague and to Charles V in Augsburg to explain the fortification plans and his triangulation system. For this achievement, the King granted him an annual pension of 100 gulden.

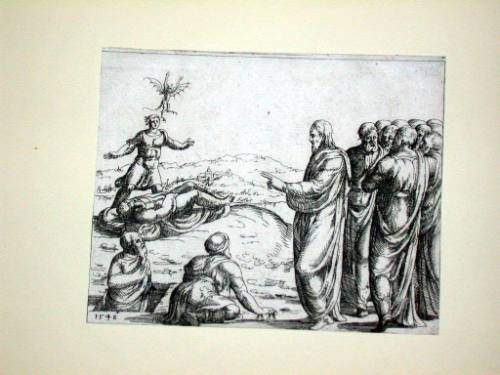

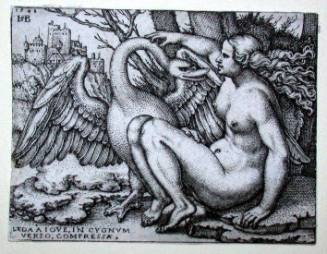

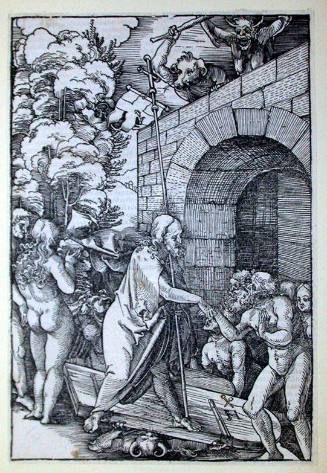

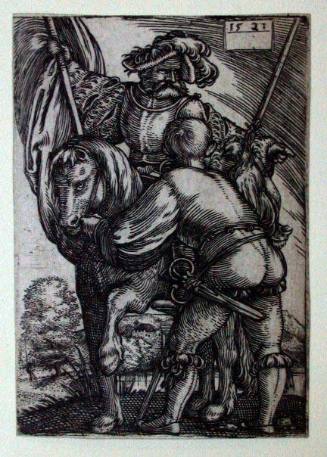

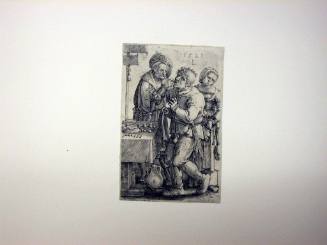

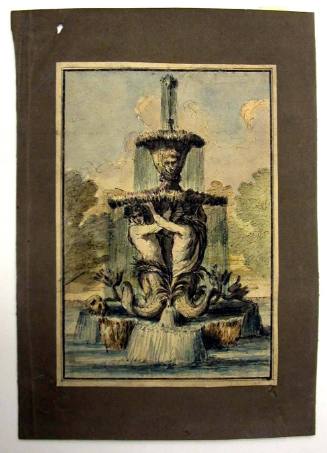

During this last decade of his life in Vienna, Hirschvogel produced most of his 300 etchings. He was one of the first etchers to make regular use of copper (rather than iron) plates and to experiment with multiple bites. He provided 23 etchings for the 1549 edition of the Rerum Moscoviticarum commentarii by Sigmund Freiherr von Herberstein (1486–1566). He completed at least 113 Old and New Testament scenes, containing awkward, mannered figures, to illustrate the verses that the Hungarian reformer Peter Perényi (1502–48) composed for the Konkordanz, published only in 1550 in incomplete form. His other single sheets include 17 fanciful designs for vessels, 19 ornamental designs, 6 geometrical and column constructions, 23 coats of arms, 17 portraits, 4 self-portraits, 12 religious, mythological and historical subjects, 6 genre and animal subjects and 35 landscapes. These reveal that Hirschvogel had a much greater natural aptitude for ornament than for figural design; many of his figure studies and compositions seem derivative in character, reflecting the influence of Dürer, Sebald Beham, Hans Burgkmair, Agostino del Musi and the school of Raphael.

Hirschvogel’s reputation as a major creative graphic artist lies with his 35 landscape etchings (1545–9) in the manner of the Danube school. His interest in landscape, already evident in his earlier hunt drawings, may have been further stimulated by his map-making work and travels along the Danube. These later pure landscapes, often in a narrow horizontal format as for example Fortress on an Island , reflect the influence of Albrecht Altdorfer and Wolfgang Huber. The absence of strong shadows or atmospheric effects endows his delicate, idyllic little scenes with a sunlit transparency and tranquil mood. His achievement lies in creating a picturesque scene where calligraphic effects take precedence over a rendering true to nature. Hirschvogel took advantage of the freedom allowed by the etching needle to create wiry lines, knots and curlicues, a style encouraged by his analogous activity of etching lines through the paint layers of his stained glass.

Jane S. Peters. "Hirschvogel." In Grove Art Online. Oxford Art Online, http://www.oxfordartonline.com.proxy.lib.fsu.edu/subscriber/article/grove/art/T038266pg2 (accessed April 27, 2012).

Person TypeIndividual

German, c. 1482 - 1539/40