Katsushika Hokusai

Japanese, 1760 - 1849

Japanese painter, draughtsman and printmaker. His work not only epitomized ukiyoe (‘pictures of the floating world’) painting and printmaking but represented the essence of artistic endeavour and achievement over a period of 70 years of single-minded creativity. He was a voracious student of a huge range of artistic techniques, ranging from painting of Ming period (1368–1644) China to the styles of the Kano- school, Sumiyoshi school, Rinpa painting and his contemporaries of Edo period (1600–1868) Japan, to Western-style painting (Yo-ga; see Japan, §VI, 5(iv)). His work also covered a spectrum of art forms: nikuhitsuga (polychrome or ink paintings); surimono (‘printed things’; de luxe, small-edition woodblock prints) and nishikie (polychrome prints); woodblocks for eirihon (illustrated books) and kyo-ka ehon (illustrated books of poems called kyo-ka); and printed book illustrations for kibyo-shi (‘yellow cover’ books, often moralizing tales and adventures) and yomihon (‘reading books’, sometimes historical novels). He was one of the main shunga (erotic picture) artists of the Edo period (see [not available online]). Hokusai is thought to have made in all at least 30,000 drawings and the illustrations for 500 books. He led a life of singular variety, sustained by his inexhaustible energy. Since the late 19th century, his work has had a significant impact on Western artists such as Gauguin and van Gogh, as well as receiving universal acclaim from art lovers and critics.

1. Early and middle years, 1778–c 1810.

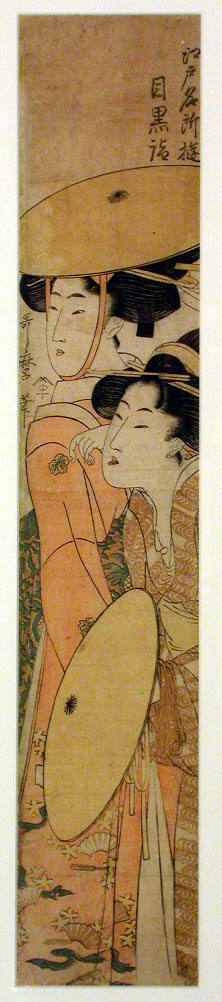

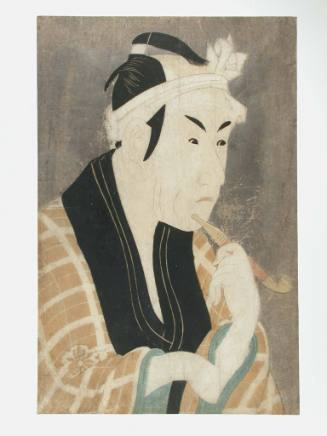

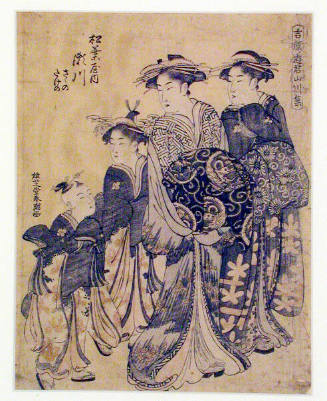

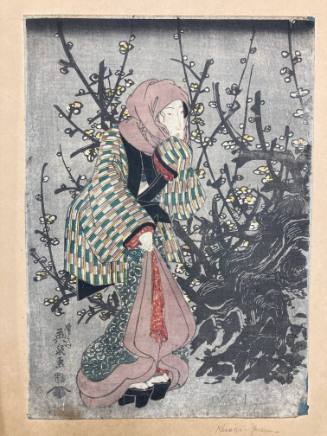

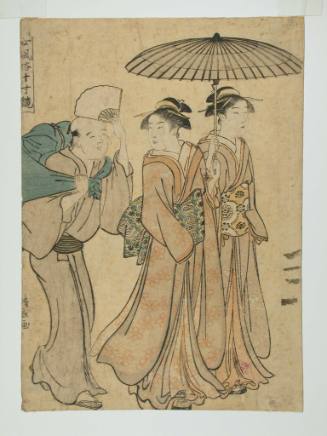

Hokusai was born in the Honjo Warigesui district of Edo. He was adopted by Nakajima Ise, a mirror maker in the service of the shogunate. From the age of 15 to 18 he was apprenticed to a woodblock engraver. In 1778, aged 19, he became a pupil of the leading ukiyoe master, Katsukawa Shunsho- (see Katsukawa, (1)), and made his debut in artistic circles in the following year, producing prints in the hosoban (narrow print) format, including yakushae (‘actor pictures’) in the style of the Katsukawa school under the go- (artist’s name) of Shunro-; he also designed illustrations for kibyo-shi. In 1795, having quarrelled with the masters of the Katsukawa school, Hokusai jettisoned the name Shunro-—thus marking the end of his period of training—and, inheriting the go- of the Rinpa-school master Tawaraya So-ri, began to produce hanshitae (final preparatory drawings for woodblock prints) for kyo-ka ehon, egoyomi (‘picture calendars’) and surimono, to which his skills were eminently suited. For the next four years, under the name of So-ri, he also produced some highly individual bijinga (‘pictures of beautiful women’; see fig.), in which the smooth lines and elegant, voluptuous charm of the forms distinguished them from the works of his contemporary Kitagawa utamaro. Of all his styles, this was perhaps the most graceful.

From 1798, having changed his name to Hokusai, he immersed himself in ukiyoe. With his vigorous, sensitive and humorous style that combined the various painting techniques of Japan, China and the West, Hokusai revitalized the ukiyoe tradition, adding landscape to its subject repertory. He became its leading exponent, along with his rival Ando- hiroshige. At the same time, he maintained enthusiastic contacts with schools unconnected with ukiyoe, such as that of Tsutsumi To-rin III, and was a diligent student of works in Western styles, such as those of Shiba ko-kan, and of such devices as vanishing perspective. During this period he contributed copiously to yomihon written by gesakusha (‘authors of gesaku’; popular fiction), such as Takizawa Bakin (1767–1848), with whom he worked from about 1807 until mutual jealousy ended their collaboration. Popular from their introduction, yomihon differed from other types of entertaining fiction in containing some moral instruction or advice. Hokusai illustrated the climax of the narrative with theatrical images that were sometimes mysterious, at other times brutal or even fantastic. He took scrupulous care to match the images perfectly to the story. Indeed, Hokusai was probably the premier Edo-period designer of black-and-white illustrations.

2. Maturity and old age, c 1810–49.

Katsushika Hokusai: Album of Sketches by Katsushika Hokusai and His…Hokusai continued (from 1810 under the name Taito) to work on kyo-ka ehon and surimono and to produce illustrated books and gafu (picture books or albums), designed for amateur artists and vehicles for his own art even late in life (see figs 1 and 2). The most famous of these, the series Hokusai manga (‘Hokusai sketches’, 15 vols, 1814–78; the last vol. published posthumously), are vivid examples of his minute workmanship, energetic brushwork, phenomenal understanding of the human figure and the acute observation he brought to this dedicated attempt to ‘illustrate the universe’. This random collection of drawings of real and imaginary subjects, executed in a multitude of styles, is a veritable encyclopedia of Japanese life and landscape and probably his most memorable work. The Hokusai manga, moreover, reveal him to have undergone training (Hasshu- kengaku) in the teachings of Hasshu- (Eight Sects) Buddhism, which had been widely diffused in the Heian period (AD 710–94). From about 1820 to 1834 (using the name Iichi), he produced primarily shikishiban (square-paper-format) surimono and nishikie of various sizes. He continued to produce the popular nishikie throughout his life. These popular prints featured mostly landscapes and birds and flowers. Hokusai also had a lifelong preoccupation with the processes of drawings and produced some charming manuals (in 1812 and 1823) setting out his favourite techniques.

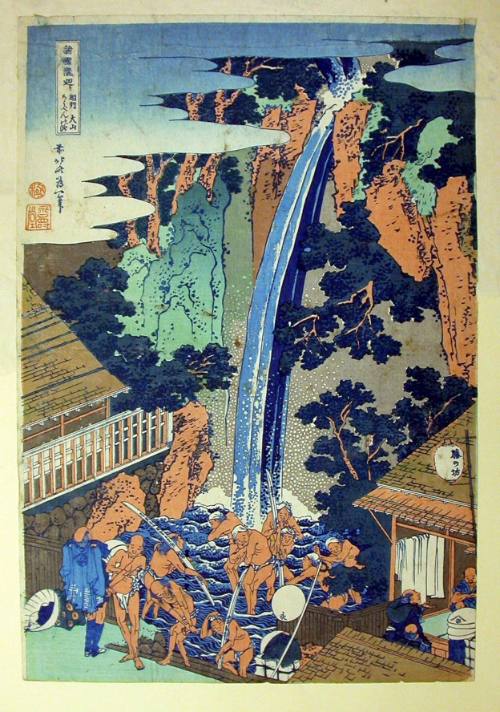

In his representative sequential collections of landscapes, the Fugaku sanju-rokkei (‘Thirty-six views of Mt Fuji’; actually 46 prints; 1831; Tokyo, N. Mus.; see fig.), the Shokoku taki meguri (‘A journey to the waterfalls of all the provinces’; c. 1832; Tokyo, N. Mus.) and the Shokoku meikyo- kiran (‘A journey along the bridges in all the provinces’; c. 1831–2), Hokusai’s individualistic style came to the fore. The scenes were not depicted as they existed in nature but instead represented images from the artist’s inner world. Many of the pictures of Mt Fuji, a sacred site in traditional belief, are composite views as if seen from several directions and in varied circumstances and reveal the artist’s extensive knowledge of his subject-matter. These works, in which imagination poses a challenge to naturalism, are quite different in character from similar landscapes by Hiroshige; Hokusai indeed created landscape pictures (fu-keiga) that others were unable to imitate. He is believed to have been the first Japanese artist to use Prussian blue, which, unlike the fugitive dyes previously used in printing, was permanent.

Hokusai also developed a novel style of extraordinarily graphic brushwork in his bird-and-flower designs (kacho-ga), which were published in tandem with his landscapes. In these too Hokusai took liberties with accurate representation, creating abbreviated or exaggerated images that seemed to express the drama of his life—which continued to offer unending challenges to his talents as a painter. His tenacious determination to attain complete mastery of his media and the application of his superb techniques to each of his works, combined with his personal qualities of rigorous rationality and deep humanity, endowed his depictions of landscapes and birds and flowers with an intensity that was absent from the temperate manner of Hiroshige.

The mature Hokusai stimulated numerous flourishing artistic movements, although he himself began to show signs of a decline in the strength of his brush compared with that of his illustrations for yomihon made before about 1830. This is confirmed by the inclusion of a number of mediocre prints in the Fugaku sanju-rokkei. Nevertheless, and in spite of intermittent paralysis, he continued his researches into painting techniques and remained indefatigably productive, as befitted his own self-description, Gakyo- Ro-jin (‘the old man mad with painting’). In 1834, aged 75, he ceased producing nishikie hanshitae and instead took his subject-matter from nikuhitsuga and printed books such as ehon. Unlike the earlier multicoloured works intended for connoisseurship, picture books (eirihon) were tending to become didactic works, in which the pictures were objects of study. Hokusai had produced such illustrations throughout his career, but in his late period he preferred to adopt unworldly subjects, such as Sho-ki (the ‘demon queller’), oni (devils) and rakan (arhats or enlightened beings), as well as Shishi (Chinese lion), dragons and tigers. The compositions so created are novel, startling, even ghostly. His nikuhitsuga display a dynamic and sublimely beautiful brush character, unparalleled for an artist of such an advanced age, and represent the culmination of the master’s achievement.

Although by now partially eclipsed in popularity by Hiroshige, he continued to produce inspired works such as the Hyakunin isshu uba ga etoki (‘A hundred poems explained by the nurse’; c. 1838) and the Shika shashinkyo- (‘A true mirror of Chinese and Japanese poems’; c. 1828–33), which evinced the interest in classical subjects he developed in later years.

3. Reputation and influence.

Hokusai’s attachment to life grew stronger as the years passed and he prayed constantly for a few more years of its enjoyment, in expectation of which he affixed the seal hyaku (‘one hundred’) to his works. At the age of 74 he had written that he had produced nothing of much value before he was 70 but that, at 110, ‘each dot, each line shall surely possess a life of its own’. However, he attained neither the age nor the artistic perfection of which he believed himself capable and died at 89, his brush apparently still near to hand. His endless quest for improvement and desire for change were reflected in his constant need to change his artist’s name and were also manifest in his restless, unconventional life. He moved house 93 times and, though adept at self-advertisement, spent most of his life in poverty. Anecdotes of his eccentric and flamboyant conduct abound. In his early years he travelled around the country giving displays of his artistic prowess that were forerunners of action painting; he sometimes created paintings 200 sq. m in area in front of festival crowds, rushing over the huge sheets of paper with a broom and a bucket of ink. In a famous competition with Tani buncho-, he dipped the feet of a chicken in red paint and let it run about freely on a sheet of paper he had just covered in blue paint; he called the resulting design Maple Leaves on a River. Hokusai had some 200 pupils, most of whose work was derivative, if not imitative. Of the more notable, Hokuju (fl c. 1802–34) created many attractive landscape prints, and Hokkei produced some admirable figure prints and elaborately printed surimono. Little is known, however, about many aspects of Hokusai’s life and work, nor is there a full catalogue of his extant works.

Masato Naito-. "Katsushika Hokusai." In Grove Art Online. Oxford Art Online, http://www.oxfordartonline.com.proxy.lib.fsu.edu/subscriber/article/grove/art/T046003 (accessed May 8, 2012).

Person TypeIndividual