Tōshūsai Sharaku

Japanese

Japanese woodblock-print designer. He remains one of the most enigmatic figures in the history of ukiyoe (‘pictures of the floating world’) woodblock prints (see Japan, §IX, 3(iii)). Sharaku was active for just under one year, from May 1794 to January 1795, during which time he is said to have produced 146 prints, of which 136 are yakushae (‘pictures of actors’), two are mushae (‘pictures of warriors’), six are sumoe (‘pictures of sumo’), one depicts Ebisu, one of the seven Gods of Good Fortune (Sohichifukujin), and one is a stencilled image (kappazuri) of the folk goddess Otafuku (or Okame). All of these except Otafuku are nishikie (‘brocade pictures’; full-colour prints) published by the Edo publisher Tsutaya Ju-zaburo- (1750–99). Several brush paintings have been tentatively attributed to Sharaku, including preliminary studies for his yakushae and sumoe.

1. Identity and background.

Several conflicting theories have been put forward concerning Sharaku’s identity. The first was proposed by O-ta Nanpo (1749–1823) in Ukiyoe ruiko- (‘Biographical notes on ukiyoe’). O-ta stated that Sharaku produced yakusha nigaoe (‘likenesses of actors’) but that his excessive naturalism gave his subjects an unusual appearance and that as a result his works were only published for just over one year. In a later revision of the Ukiyoe ruiko-, Shikitei Sanba (1776–1822) recorded that Sharaku lived in the Hatcho-bori district of Edo under the name To-shu-sai. Other reliable sources state that he produced prints of the actors Godaime Ko-shiro-, Hanshiro- and others, that he was commonly known as Saito- Ju-ro-bei, lived in Edo Hatcho-bori during the 1790s and was a no- actor from the Awa domain (now Tokushima and Hyo-go Prefect.). Kurth (1910) was one of the earliest Sharaku scholars to link the artist to the no- actor Saito- Ju-ro-bei. In the 1960s this theory was challenged and attempts were made to identify Sharaku with other personalities, for example the artists Utagawa Toyokuni, Katsushika Hokusai, Maruyama O-kyo, Shiba Ko-kan, Sakai Ho-itsu, the publisher Tsutaya Ju-zaburo-, the poet Tani Sogai and the actor Nakamura Konozo-. None of these alternative identities, however, has been proven. In 1976 new evidence was discovered. A residential roster (Shoka jinmei Edo ho-gakuwari; ‘The names of various people in various thought directions in Edo’), compiled by the actor Segawa Tomitaro- III in 1818, carries the signature ‘Sharakusai’ under the address Hatcho-bori Jizo-bashi, and a map of Edo in 1854 records that a man named Saito- Yoemon lived next to the Muratas in the north-east corner of Jizo-bashi (Nakano). In 1983 no- records revealed that the names Ju-ro-bei and Yoemon were used by alternate generations of the Saito- family. These records proved that the no- player Saito- Ju-ro-bei was 33 years old in 1794, making it highly likely that he was indeed Sharaku (Uchida).

The kabuki theatre during Sharaku’s period of activity was stagnating. The three major theatres in Edo, the Nakamuraza, Ichimuraza and Moritaza, were unable to stage plays because of financial difficulties, and performances took place at smaller theatres, such as the Miyakoza, Kiriza and Kawarazakiza. The performances and actors at these theatres provided the subject-matter for many of Sharaku’s prints. In November 1794 Osaka’s foremost playwright, Namiki Gohei I (1747–1808), moved to Edo and instigated reforms in the Edo kabuki, introducing the Kamigata (Kyoto–Osaka region) style to Edo audiences. Kamigata actors such as Nakamura Noshio II (1759–1800) and Kataoka Nizaemon VII (1755–1837) had also moved to Edo, and it is therefore not surprising that Sharaku’s work shows the influence of Kamigata artists such as Nicho-sai ( fl 1780–1803), Suifutei ( fl 1782–3) and Ryu-ko-sai ( fl 1772–1809).

2. Works.

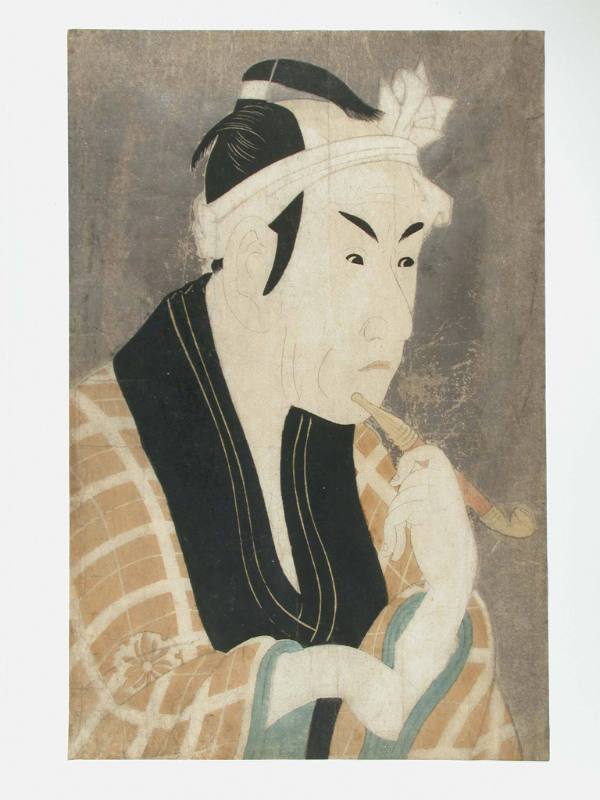

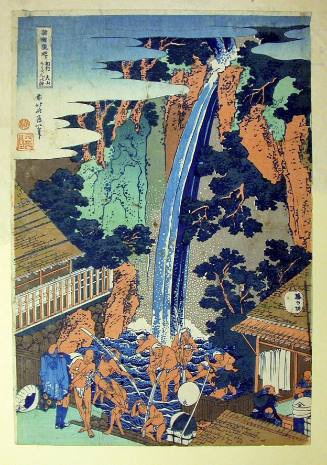

To-shu-sai Sharaku: Actors Nakamura Wadaemon and Nakamura Konozo-, woodblock print,…Sharaku’s work can be divided into four stylistic periods. The first is represented by 28 pieces from kabuki performances in May 1794. The prints depict half-length figures and are large-format (o-ban) kirazuri (prints with mica background). The humorous renderings of figures show no attempt at idealization; Sharaku’s manner of emphasizing features is seen in the series Katakiuchi noriai banashi (‘A medley of tales of revenge’; prints), Hana ayame Bunroku Soga (‘The iris Soga of the Bunroku’; prints), Koinyo-bo- somewake tazuna (‘The loved wife’s part-coloured reins’; 100 prints; Tokyo, N. Diet Lib.) and Yoshitsune senbon zakura (‘Yoshitsune of the 1000 cherry trees’; 100 prints; Tokyo, N. Diet Lib.). These works capture the personality of the actors, and many of Sharaku’s most representative works are from this period (see fig.). That Tsutaya Ju-zaburo- permitted Sharaku to use the expensive kirazuri technique for his first works seems to indicate the publisher’s unusual expectations of the young artist.

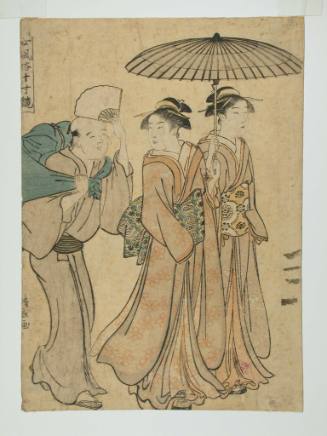

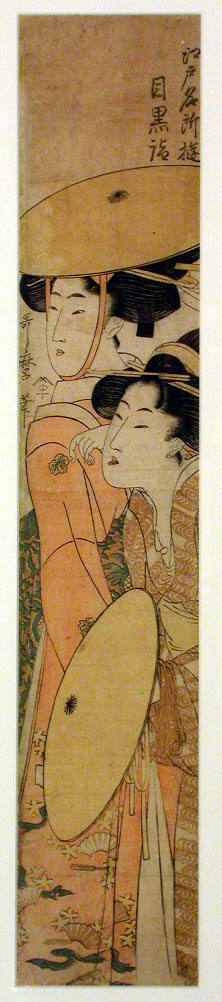

The second period is represented by 38 prints from kabuki performances in July and August 1794, all of which are full-figure prints of a quality equal to work from Sharaku’s first period. The narrow-format (hosoe) works with one figure are excellent, as in 13 of the 17 prints in the Miyakoza, for example Keisei sanbon karakasa (‘The courtesan and the three umbrellas’). Also outstanding are the large-format prints depicting two actors. Sharaku’s strong compositions are exemplified by the tension and contrast created in his two-figure prints. Works from the first two periods are signed ‘To-shu-shai Sharaku ga’ (‘pictures by To-shu-sai Sharaku’).

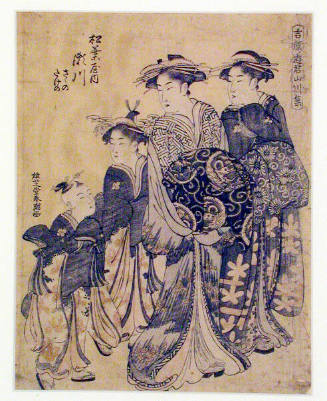

Works from the third period are represented by 64 prints including sumoe and yakushae for kabuki performances during November and lunar November 1794. During this phase of his career Sharaku’s work changed dramatically. The prints are all half-figure pieces with solid yellow backgrounds, but in contrast to the opulence of the half-figure prints of the first period, they are characterized by a simplification in the printmaking process, a drastically compromised quality of the imagery and an abrupt waning of his former expressive power. His narrow-format full-figure pieces also changed, and some prints dating from this period have been described as undeveloped and trite. All but six works are signed ‘To-shu-sai Sharaku ga’; the remainder are signed ‘Sharaku ga’ (‘pictures by Sharaku’).

The final period includes 16 prints depicting the New Year kyo-gen performances of 1795, sumoe and others. These provide further evidence of Sharaku’s creative decline, as seen in the mannered and pedestrian quality of the Nido no kake katsuiro Soga (‘The ever-victorious Soga’) series of three narrow-format full-figure prints.

Despite Sharaku’s prodigious output, he had little impact on the world of ukiyoe. While Kabukido- Enkyo- (1794–1803) and Utagawa Kunimasa are considered to resemble him in style, Sharaku remains an isolated figure in the history of ukiyoe. He was unrecognized in Japan until the American art historian and educator Ernest Fenollosa commented on the extreme ugliness of his subjects in an ukiyoe catalogue (1898).

Susumu Matsudaira. "To-shu-sai Sharaku." In Grove Art Online. Oxford Art Online, http://www.oxfordartonline.com.proxy.lib.fsu.edu/subscriber/article/grove/art/T085804 (accessed May 8, 2012).

Person TypeIndividual