Frans Hals

Dutch, 1580/5 - 1666

In the field of group portraiture his work is equalled only by that of Rembrandt. Hals’s portraits, both individual and group, have an immediacy and brilliance that bring his sitters to life in a way previously unknown in the Netherlands. This effect, achieved by strong Baroque designs and the innovative use of loose brushstrokes to depict light on form, was not to the taste of critics in the 18th century and the early 19th, when his work was characterized as lazy and unfinished. However, with the rise of Realism and, later, Impressionism, Hals was hailed as a modern painter before his time. Since then his works have always been popular.

1. Life and work.

The introduction to the second edition of Karel van Mander’s Schilderboeck (1618) mentions Hals as one of his pupils. This apprenticeship would have lasted until 1603 at the latest. Hals may have begun his career by painting scenes of merry companies, such as the Banquet in a Park (c. 1610; ex-Kaiser Friedrich Mus., Berlin; destr.). In 1610 he became a member of the Guild of St Luke in Haarlem and married Annetgen Harmensdr. (d 1615); their first son, Harmen, was born in 1611, the year of Hals’s earliest dated painting, a portrait of Jacobus Zaffius (1534–1618), of which only a portion survives (1611; Haarlem, Frans Halsmus.). Hals’s distinctive style can already be seen in this work: the loose brushstrokes, applied ‘wet on wet’ without erasure, the lively characterization and the strong illumination of the head, the light always coming from the left.

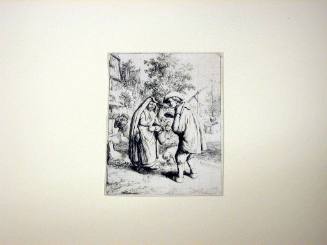

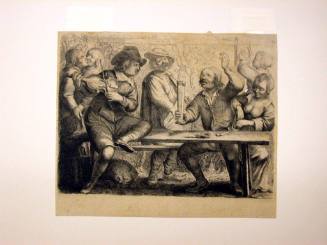

During the second decade of the 17th century Hals painted single and double portraits, a civic guard piece and genre paintings. The portraits adhere strictly to Dutch conventions established by such artists as Cornelis Ketel and Paulus Moreelse. Hals also borrowed from the portrait engraving tradition such motifs as the oval trompe-l’oeil stone frame, which he used several times up to 1640. From 1616 to 1625 he was a member of the Haarlem chamber of rhetoric called De Wijngaertrancken. His connection with this organization is reflected in a portrait (1616; Pittsburgh, PA, Carnegie) of Pieter Cornelisz. van der Morsch (1583–1628), a rhetorician in Leiden, as well as in genre scenes of Shrove Tuesday revellers (see fig.). Also in 1616 he painted his first militia piece: the Banquet of the Officers of the St George Civic Guard Company (Haarlem, Frans Halsmus.), of which he himself had become a member in 1612. Its composition is borrowed from a militia piece by Cornelis Cornelisz. van Haarlem (1599; Haarlem, Frans Halsmus.) and a design for a civic guard banquet in a drawing (c. 1600–1610; Amsterdam, Rijksmus.) by Hendrick Goltzius. However, Hals enlivened the effect by giving each of the diners more individual space.

The first of a long list of creditors’ claims on Hals dates from 6 August 1616; it relates to purchases of paintings, indicating his activity as a dealer or collector. On that date Hals was in Antwerp, probably on family business; he was back at Haarlem by 11 November. In 1616 his cousin and namesake Frans Hals was in trouble with the Haarlem authorities for being drunk and ill-treating his wife; he afterwards settled in Antwerp. (This cousin was confused with his more famous relative by van der Willigen.) On 12 February 1617 the painter Frans Hals married Liesbeth Reyniers, and in 1621 he and his brother Dirck were mentioned for the first time in a literary source (Ampzing). While in Antwerp, Frans probably came under the influence of Rubens, for his Portrait of a Married Couple in a Garden (early 1620s; Amsterdam, Rijksmus.) resembles the latter’s Rubens and his Wife Isabella Brant in the Honeysuckle Bower (1609–10; Munich, Alte Pin.). Hals’s sitters were probably the Haarlem diplomat and cartographer Isaac Massa (b 1587) and Beatrix van der Laen, who were married in 1622. Other paintings from the 1620s include a Portrait of a Family in a Landscape (c. 1620; Viscount Boyne, on loan to Cardiff, N. Mus.) and numerous genre pieces of children and young men drinking, smoking and making music. The portrait of Jonker Ramp and his Sweetheart (1623; New York, Met.) has been interpreted as representing the Prodigal Son, while the children drinking and making music are usually interpreted as standing for the Five Senses or the Cardinal Sins. The prominent role of children is new in Dutch painting. Typical of Hals’s genre work is its portrait-like character: most consist of only one or two figures and practically no background (which was emphasized more by other contemporary genre painters). Hals’s portraits and genre pictures of the 1620s are also marked by their vivid colouring, plein-air effects, shifting contours and foreshortenings. The tonality is lighter than in the previous decade, probably under the influence of the Utrecht Caravaggisti, which affected both Hals’s style and his subject-matter: it was Caravaggisti who set the fashion for drinkers, lute-players and life-size, half-length single genre figures. Hals also cut the figures off and used a di sotto in sù viewpoint, with strong contrasts of light and dark in the hands and faces, though not in the figures’ clothing.

Apart from the supposed scenes of the Prodigal Son, Hals’s only other known biblical paintings are his St Luke and St Matthew (both c. 1625; Odessa, A. Mus.), from a series of the Four Evangelists; a third picture from the series, of St Mark (priv. col., see 1989–90 exh. cat., p. 193), was discovered in 1974. Sources also mention a Cain, a Magdalene and a Denial of St Peter (all untraced). Hals painted his second and third militia pieces c. 1627 (both Haarlem, Frans Halsmus.), depicting the civic guard companies of St Hadrian and St George, and about the same time executed the portrait of Verdonck Holding a Jawbone (c. 1627; Edinburgh, N.G.). The latter was one of several of Hals’s works that were altered at a later date: in this case a hat was added and the jawbone replaced by a wine-glass. The original composition is a unique example of a contemporary sitter portrayed with the attribute of a biblical character (Samson).

Frans also continued to trade in works of art. On 17 May 1627 Dirck stood surety for his purchases at an auction of paintings, and in 1630 Frans paid 89 guilders in Amsterdam for Hendrick Goltzius’s painting of Tityus (1613; Haarlem, Frans Halsmus.) and sold it through an intermediary to the city of Haarlem for 200 guilders. In 1629, for 24 guilders, he cleaned some canvases for the monastery of St John at Haarlem.

About 1630 Frans painted several outdoor genre scenes of fisher boys and girls (e.g. Dublin, N.G.; these are not accepted by Grimm, 1972), the subjects of which have been interpreted as symbolizing laziness. Dating from about the same period or slightly earlier are the Malle Babbe (c. 1633–5; Berlin, Gemäldegal.), the Gypsy Girl (c. 1628; Paris, Louvre), the Pickled Herring (c. 1628–30; Kassel, Schloss Wilhelmshöhe), ‘The Mulatto’ (c. 1628–30; Leipzig, Mus. Bild. Kst.) and the Merry Drinker (c. 1628–30; Amsterdam, Rijksmus.). The 1630s also marked the peak of Hals’s career as a portrait painter. The early bright colours have been abandoned in favour of a more monochrome effect; the composition is more unified and simple, the poses more frontal. Besides the many single and double portraits, there is a small family group of c. 1635 (Cincinnati, OH, A. Mus.). Hals also painted the civic guard company of St Hadrian again, this time in the open air (c. 1633; Haarlem, Frans Halsmus.); in contrast to the earlier version, the officers are not placed in order of rank. In 1633 he received a commission from Amsterdam to paint another militia piece, the Company of Capt. Reynier Reael and Lt Cornelis Michielsz. Blaeuw (the ‘Meagre Company’; Amsterdam, Rijksmus.), for which he was at first offered 60 guilders per person, afterwards 66 guilders. The work led to a dispute, as Hals could not get the group of men to pose together in Amsterdam; subsequently he refused to return there, and they would not go to Haarlem. Consequently Pieter Codde took over the commission, which he completed in 1637. In 1635 Hals was also involved in a dispute with Judith Leyster, who had been his pupil c. 1630 and stood godmother to his daughter Maria in 1631. Contrary to Guild regulations, Hals took over a pupil of hers. Also in 1635 he was in arrears with his Guild contributions. A few years later he painted himself in the background of the Officers and Sergeants of the St George Civic Guard Company (c. 1639; Haarlem, Frans Halsmus.). This is his only known self-portrait, apart from a painting known only from copies (e.g. Indianapolis, IN, Clowes Fund Inc., priv. col., on loan to Indianapolis, IN, Mus. A.).

After these peak years, the 1640s show a falling-off in commissions. Public taste increasingly favoured the smooth manner of such painters as Ferdinand Bol, Govaert Flinck and Bartholomeus van der Helst, all active in Amsterdam. Probably under their influence, Hals began to paint portraits with a more aristocratic air, and more static and less ostentatious poses. The backgrounds are darker, usually golden-brown or olive-green, and the clothing is predominantly black. It seems that he no longer painted genre scenes. Large commissions were for the sober portrait of the Regents of the St Elizabeth Hospital at Haarlem (c. 1641; Haarlem, Frans Halsmus.), the composition of which was probably borrowed from Thomas de Keyser, and two family portraits in a landscape (both c. 1648; Madrid, Mus. Thyssen-Bornemisza, and London, N.G.).

In 1642 family problems arose. Hals’s feeble-minded son Pieter was locked up as a public danger; and on 31 March the painter’s wife tried to have their daughter Sara committed to a workhouse owing to her loose morals. In 1644 Hals became an inspector (vinder) of the Guild of St Luke in Haarlem. His last dated works are of 1650. Those ascribed later dates are for the most part dark and sober in coloration, the paint is thin and the brushstrokes loose and broad. The poses are static and frontal, in line with the new classicizing trend. Unique in the portrait iconography of 17th-century Holland are the pendant portraits (both c. 1650) of Stephanus Geraerdts (Antwerp, Kon. Mus. S. Kst.) and Isabella Coymans (Paris, Baronne Edouard de Rothschild priv. col.): the two paintings (for illustration see Pendant) are linked by the wife’s gesture, as she hands her husband a rose.

In 1652, on account of an unpaid baker’s bill of 200 guilders, a distraint was levied on Hals’s furniture and meagre collection of paintings: two of his own works, two by one of his sons, one by van Mander and another by Maarten van Heemskerck. The last documented creditor’s demand dates from 1661 and relates to purchased paintings. In the same year Hals was exempted from Guild contributions on account of his age. In 1662 the burgomasters of Haarlem made a lump sum payment of 50 guilders and granted him a pension of 150 guilders a year, which was raised to 200 guilders in 1663. On 22 January 1665 he stood surety for a debt of 458 guilders incurred by his son-in-law, Abraham Hendrix Hulst. He was probably able to do so because of the commissions for two group portraits: the Regents of the Old Men’s Almshouse and the Regentesses of the Old Men’s Almshouse (both c. 1664; Haarlem, Frans Halsmus.). (It is sometimes supposed that Hals became an inmate of the same old men’s home, but there is no documentary evidence for this.) These and other late works are marked by a very summary use of colour, loose brushwork in flowing paint and very imprecise outlines. Some critics see this as the climax of Hals’s virtuosity as a painter; others put it down to old age, stiffness and failing sight.

2. Working methods and technique.

Hals’s oeuvre consists of oil paintings on canvas or panel and three small portraits on copper. The works vary in size from very small portraits (145×120 mm) to life-size portrait groups. No drawings or prints can be ascribed to him with certainty. He probably painted directly from the model, and very fast. In correspondence concerning the ‘Meagre Company’, he promised that the sittings would not take long. No underdrawing has been detected. No doubt some small portraits were intended as preliminary studies for larger ones. Pigment analysis has shown that, especially in the flesh parts, there is no clear division between the layers of paint, indicating that he painted alla prima or ‘wet on wet’. Before c. 1626, Hals applied a ground of white and grey under the flesh colours. His priming generally consisted of a light-coloured layer, with a thinner, darker one above it, the colour of which varied from one painting to another. His colour schemes, which developed from bright to monochrome, were achieved with a fairly limited palette. In the Portrait of a Lady (1627; Chicago, IL, A. Inst.), only six pigments have been identified. The umber-coloured background seen in many of his portraits was achieved with a mixture of lead white, yellow ochre and black. In his later work, only four colours have been found: black, white, Venetian red and light ochre.

Hals’s work derives its specific character from the loose brushwork and thin, flowing paint applied alla prima; the texture of the canvas is generally still clearly visible. It is also typical of him that the thickness of the pigment, the amount of detail and the style of brushwork can vary considerably in one and the same work. The faces in the portraits are invariably more carefully painted than the hands and clothing; the brushstrokes often flow so smoothly into one another that the separate strokes can scarcely be perceived. However, the hands and clothing are painted with parallel strokes varying in length and breadth. The somewhat ‘frayed’ appearance of his outlines, increasingly evident in the late work, is achieved by consecutive overlapping strokes. His genre scenes are much more loosely painted than the portraits of the same period, with clearly visible brushstrokes, although in Hals’s later period this looser technique was also found in the portraits. Until c. 1626 the colour is generally thin and half transparent, with opaque, wax-like highlights; subsequently, the pigment becomes more opaque and less contrasting. In the 1650s it again becomes more transparent; while the latest works, from the 1660s, are characterized by the use of opaque and transparent colour in a single painting. Although the poses and grouping of figures used by Hals are broadly traditional, nevertheless his portraits make a much livelier impression than those of his contemporaries: this is due not only to his handling of the paint, but also to the sense of unfinished movement: heads turn away and somewhat to one side, half-open mouths seem about to speak, laugh or smile (quite unusual in contemporary portraiture). All of this contributes to the sense of animation, as do the suggestion of movement in hands and the way in which the sitters lean slightly back, forward or sideways.

Hals evidently had apprentices, as is shown by the dispute with Judith Leyster. His son-in-law Pieter van Roestraten stated in 1651 that he had worked with Hals for five years, and during Hals’s lifetime copies of his works, perhaps from his own studio, were already in circulation. Sometimes he collaborated with other painters: the female figure in Fruit and Vegetable Seller (c. 1630; Burwarton Hall, Salop), by Claes van Heussen (c. 1600–after 1630), is thought to be by Hals. A document of 1651 states that Willem Buytewech executed the painted borders for two of Hals’s portraits, and Slive has ascribed the background of some of Hals’s landscapes to Pieter de Molyn.

3. Character and personality.

Since the early 18th century, Hals has been persistently represented as a profligate and toper. The earliest account of his character is given by the German artist Mattias Scheits (see Bode), who claimed Hals was ‘somewhat high-spirited in his youth’. His reputation as a drunkard originated with Houbraken, who said he was so drunk every evening that his pupils had to help him home. According to Houbraken, Hals exploited his pupil Adriaen Brouwer; he further related that Hals once met Anthony van Dyck, on which occasion the two artists painted each other’s portrait. The many claims for debt, and the grants made to Hals at the end of his life, appeared to confirm this reputation. Due to a confusion of identity with his namesake and cousin, Hals continued to be regarded as an alcoholic, and as a wife-beater. His supposedly unappealing portraits of the regents and regentesses of the old men’s home were thought by some to be a form of revenge on the authorities who had treated him callously in his impoverished old age.

The truth is hard to determine. Hals’s alleged chronic drunkenness is hardly confirmed by two outstanding bills of 1644, amounting to about 5 guilders altogether, and another of 1650 for 31 guilders, which in any case he refused to acknowledge. The many demands for arrears of rent, provisions and footwear illustrate the regular financial troubles of a large family, but do not prove constant poverty. His output was relatively small, and his income therefore probably irregular. It is unclear whether or not he was impoverished in later life: he received an official grant, but was then suddenly able to stand surety for more than twice the amount. His behaviour over the Amsterdam militia piece seems to show that he had little ambition to extend his clientèle beyond Haarlem. His membership of a militia company and a chamber of rhetoric may testify to his social standing, while, as Scheits observed, the later grants may have been made in recognition of his eminence as a painter.

Hals’s artistic connections were evidently limited to his Haarlem colleagues. In 1629, in his capacity as a guild official, together with Pieter de Molyn and Jan van de Velde the younger, he carried out an inspection of the conditions of imprisonment of their fellow artist Johannes Torrentius, and in 1642, with Frans Pietersz. de Grebber (1573–1649), Pieter de Molyn, Cornelis van Kittensteijn ( fl c. 1600) and Salomon van Ruysdael, he presented a petition concerning a sale of paintings for the benefit of Haarlem artists. His only conflict with the guild was over the dispute with Judith Leyster; he was not its only member to be in arrears or in default over contributions, and this did not prevent his being appointed an inspector in 1644.

4. Patrons and clients.

The majority of Hals’s portraits were commissioned, but he may have had an intermediary for the sale of his genre paintings; in 1631 his landlord Hendrik Willemsz. den Abt offered a number of pictures for sale, including four of Hals’s works and copies of others by him. (These may have been in his possession as a pledge in respect of board and lodging.) In 1634 two equestrian portraits and a Vanitas by Hals were offered as lottery prizes. Some of his portraits were engraved at a very early date and may have been painted for that purpose: most of the prints, however, particularly the genre subjects, were not made until after his death. Hals’s clients were the wealthiest and most influential people in the city of Haarlem, including the Olycan family of brewers. There were only a few exceptions to this, René Descartes being the most notable; Hals painted his portrait c. 1649 (Copenhagen, Ny Carlsberg Glyp., on loan to Copenhagen, Stat. Mus. Kst). Members of the Amsterdam banking family of Coymans were among his faithful customers. Isaac Massa, who had his portrait painted three times by Hals, and perhaps his wedding portrait also, was present at the baptism of Hals’s daughter Adriaentgen in 1623. Hals also painted portraits of his fellow-artists, including Adriaen van Ostade (Washington, DC, N.G.A.), Vincent Laurensz. van der Vinne (c. 1655–60; Toronto, A.G. Ontario) and Frans Post (USA, priv. col., see 1989–90 exh. cat., no. 77).

5. Critical reception and posthumous reputation.

Hals’s characteristic loose brushwork was imitated only for a time by his son Jan Hals and by Judith Leyster. Houbraken listed as his pupils Frans’s brother Dirck, his sons, his son-in-law Pieter van Roestraten, Adriaen Brouwer, Dirck van Delen, Adriaen van Ostade, Vincent van der Vinne and Philips Wouwerman; the last-named was mentioned as Hals’s pupil by Cornelis de Bie as early as 1661. Many painters are said to have been influenced by Hals: Jan Miense Molenaer, Hendrick Pot, Thomas de Keyser, Jan Verspronck, Pieter Codde, Pieter Claesz. Soutman, Bartholomeus van der Helst, Jan de Bray, Gabriel Metsu, Gerard ter Borgh and finally Jan Steen, who represented the Pickled Herring by Hals in his Christening Party (Berlin, Gemäldegal.).

Hals’s individual style and the liveliness of his portraits were recognized already in his lifetime. Samuel Ampzing described the Banquet of the St Hadrian Civic Guard Company (c. 1627) as ‘very boldly painted after life’. In 1647 Theodorus Schrevelius (1572–1653), whom Hals painted in 1617 (Ascona, Bentinck-Thyssen priv. col., on loan to Luxembourg, Mus. N. Hist. & A.), drew attention to Hals’s forceful manner and declared that his portraits seemed to breathe. De Bie described him as ‘miraculous excellent at painting portraits or counterfeits which are rough and bold, nimbly touched and well-ordered. They are pleasing when seen from afar, seeming to lack nothing but life itself.’ However, in 1660 H. F. Waterloos (d 1664) criticized Hals’s portrait of the Amsterdam clergyman Herman Langelius (c. 1660; Amiens, Mus. Picardie): Hals, he said, was too old, his eyes too weak, his ‘stiff hand too rude and artless’; he added, however, that Haarlem was proud of Hals’s skill and early masterpieces. It was even said that van Mander himself moved to Amsterdam because his pupil Hals was more famous than he.

Despite such praise, there is reason to doubt Hals’s status among his contemporaries, and his fame was fairly localized. Notwithstanding the great demand for portraits, they were regarded as an inferior form of art; Hals signed his full name only on his genre pieces. He received only average sums for his painting: the 66 guilders for each figure he was offered for the ‘Meagre Company’ contrasts with the 100 guilders per figure Rembrandt received for the ‘Night Watch’ (Amsterdam, Rijksmus.). Until the 19th century Hals’s paintings continued to fetch low prices, about 15 guilders on average. He painted few self-portraits, which were an important means of enhancing status. For such a rapid worker, his output seems very slight: even at its peak, fewer than ten portraits a year, although it may be that as his work was undervalued after his death, much of it has been lost.

Hals’s rough style of painting did not appeal to 18th-century taste. Joshua Reynolds and Goethe thought his work lacking in finish, and on the few occasions when Hals is mentioned in literature before the 1860s, this lack of finish is blamed on his dissolute way of life. From the 1860s onwards, however, opinions rapidly changed under the influence of Théophile Thoré. Both Hals’s style and his way of life were now considered artistic, spontaneous, full of joy and individuality—qualities taken to exemplify the new Dutch Republic of the 17th century. After long neglect, he was ranked next to Rembrandt and hailed as an exponent of modern ideas of painting: ‘Frans Hals est un moderne’ (L’Art moderne, 1883, p. 302). Gustave Courbet copied his Malle Babbe (1869; Hamburg, Ksthalle), and van Gogh extolled his sense of colour and lively characterization. The prices paid for his works (and the number of forgeries) rose rapidly; in 1865 the 4th Marquess of Hertford and Baron Rothschild competed at auction for the Laughing Cavalier (1624; London, Wallace) and bid up the price to an unprecedented level for a painting. Although the 19th-century estimation still persists, since the 1960s critics have endeavoured to place Hals’s work in the 17th-century context as regards both style and iconography. The frequent lack of a signature and date on his works has provoked much dispute: Valentiner ascribed c. 290 works to Hals, Trivas 109, Slive c. 220, Grimm 168. There is, however, much more agreement on issues of chronology, although the early critics generally dated the genre pieces later than do more recent ones.

Ingeborg Worm and Agnes Groot. "Hals." In Grove Art Online. Oxford Art Online, http://www.oxfordartonline.com.proxy.lib.fsu.edu/subscriber/article/grove/art/T036318pg1 (accessed May 8, 2012).

Person TypeIndividual

Dutch, c. 1597 - 1662