Image Not Available

for Jan Steen

Jan Steen

Dutch, 1626 - 1679

Dutch painter. He is best known for his genre scenes depicting busy interiors, often with a strongly moralizing theme and frequently illustrating Dutch sayings. These cheerful and disorderly scenes themselves gave rise to the Dutch expression ‘a Jan Steen household’. His work, in which his goal seems to have been to combine narrative, instruction and entertainment, revives the moralizing tradition of earlier Dutch genre painters. Yet his inquisitive mind provoked him continuously to explore new styles and themes, an attitude probably stimulated by his frequent moves between Dutch cities. Steen was a prolific artist (although the quality of his work varies greatly), and, as well as his many genre pieces, he executed biblical and mythological subjects and a few portraits; he particularly excelled in the depiction of children. At the end of his life he produced paintings that foreshadow the Rococo idylls of 18th-century artists.

1. Life.

Steen was the son of a brewer. In 1646 he enrolled, aged 20, as a student of Leiden University, where, like Rembrandt, he studied for only one year. He must have begun his professional training in 1647. Three painters are mentioned in early sources as his teacher, of whom the Haarlem genre painter Adriaen van Ostade seems the most probable. In 1648 Steen joined the newly established painters’ guild in Leiden. His amazingly short period of training may have been compensated for by drawing lessons in his youth. In 1649 he married Grietje, a daughter of the landscape painter Jan van Goyen (another of his proposed teachers), indicating that he was considered capable of supporting a family through his work. However, he may never have planned to be a full-time painter. In 1654 Steen’s father rented a brewery in Delft for his son, a project that was shortlived and unsuccessful. With the whole of the brewing industry, the fortunes of the Steen family plummeted. Jan Steen lived in a number of different places but always kept contact with the guild of his native Leiden. Surprisingly, he seems to have left no traces as a painter in the Delft archives. From 1661 until 1670 he lived in Haarlem, where he created his most important works. From 1670 until his death he lived in the Leiden house he had inherited from his father, and from 1672 onwards, the year of the disastrous French–German invasion, he kept a tavern in this house. Financial difficulties and low prices for his art marked most of his career.

2. Work.

Unlike most 17th-century Dutch painters who sought a successful combination of theme, style and compositional methods, to which they then adhered throughout their career, Steen never found such repose, either in terms of style or range of subjects. He was constantly studying and trying to emulate the work of numerous colleagues. The fact that he was never very successful during his lifetime may also have motivated him to keep looking for new possibilities in different directions. This has earned him the ill-deserved reputation of being fickle and too easily influenced.

(i) Stylistic development.

It is not easy to reconstruct Steen’s development, since he dated only a few of his works. Despite his lack of success during his lifetime, however, he must have been immensely popular in Holland in the early 18th century, when his signature was added to many works more or less closely connected with his style and subject-matter. Numerous copies and imitations originated in that period. These are not always easily distinguishable from genuine works; moreover, a certain form of crude humour in a painting seems to have been enough for some dealers and collectors to consider an attribution to Jan Steen.

(a) 1650s.

That Adriaen van Ostade was presumably Steen’s teacher, as is now generally accepted, is supported by early works, such as The Dentist (1651; The Hague, Mauritshuis), that reflect the Haarlem tradition of low-life genre but are still somewhat uncertain in style and execution. Probably earlier still are two peasant scenes (both The Hague, Mauritshuis) and The Fortune-teller (Philadelphia, PA, Mus. A.). It was not until 1653 that the artist evolved his own recognizable artistic personality, as in his Village Wedding (1653; Rotterdam, Mus. Boymans–van Beuningen). The long-held belief that Steen’s father-in-law, Jan van Goyen, was his teacher led to the attribution to Steen of a number of landscapes with genre-like figures, although most of these seem not to be by Steen’s hand, but some are signed.

Steen’s contact with the art of Delft, Rotterdam and Dordrecht had a lasting effect on his oeuvre, which makes it all the more amazing that he did not live longer in Delft. He studied the work of Pieter de Hooch, Nicolaes Maes, Samuel van Hoogstraten and Hendrick Sorgh in great detail. Since low-life genre in the days of van Ostade had lost almost all of its former predilection for dramatic action, Steen turned to other genre painters for their use of light, space and perspective as narrative elements. He was fascinated by open doors and windows that enabled contact between figures in different rooms, as in the Priest Admonishing a Woman through an Open Window (priv. col.). The result was a fusion of styles and motifs from low-life genre scenes with other genre themes. Though undated, the Cutting of the Stone (Rotterdam, Mus. Boymans–van Beuningen) can be placed in the 1650s. The exceptional portrait of a man and a girl in front of a house in Delft is dated (1655; Penrhyn Castle, Gwynedd, NT) and is roughly contemporary with the Supper at Emmaus (Amsterdam, Rijksmus.) and Christ in the House of Martha and Mary (priv. col.), the latter a rather unsophisticated variation of Vermeer’s composition of the same subject (c. 1655; Edinburgh, N.G.).

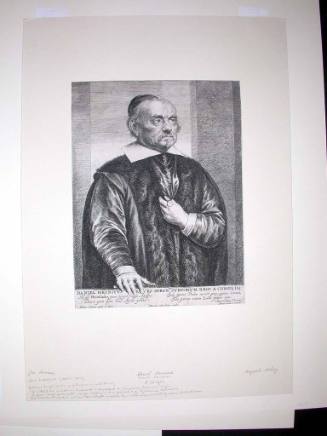

In the late 1650s Steen lived in the village of Warmond, near Leiden. There he moved away even more from the tradition of low-life genre in which he had been trained, and he became more interested in the work of Gerard ter Borch (ii), whose works he had studied earlier. Steen’s contact with Gabriel Metsu seems to date from this period. He also met Frans van Mieris (i), who was still in the earliest phase of his career; described as close friends by Houbraken, the two painters must have engaged in an intensive exchange of ideas. The highly finished, minutely detailed paintings of the Leiden school of ‘Fine Painters’ (e.g. Dou, van Mieris) fascinated Steen, but in trying to imitate their effects, he never adopted their elaborate technique. At first sight Steen’s Woman Eating Oysters (The Hague, Mauritshuis) looks like a Leiden school painting, but the unusual perspective and the abbreviated rendering of background details are completely different. Also painted in Warmond were the Acta virum probant (or Young Woman Playing a Harpsichord, 1659; London, N.G.), the Itinerant Musicians (1659; Ascott, Bucks, NT) and the portrait of Bernardina van Raesfelt (1660; The Hague, Mauritshuis).

(b) 1660s.

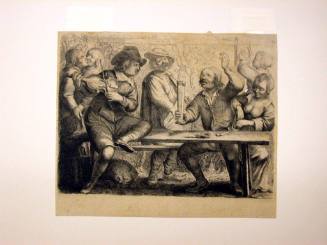

Around 1660 there was a rather superficial connection between Steen’s work and that of the Utrecht artist Nicolaes Knüpfer (c. 1603–55), the third of Steen’s supposed masters; the contact between the two artists may have come about through Metsu, who was a pupil of Knüpfer and whose work strongly influenced Steen in the 1660s. In Haarlem, where Steen became a guild member in 1661, he tried to achieve a scale and monumentality, combined with a freedom of brushwork, that were never before seen in Dutch genre painting. The great days of Haarlem genre art were over, but Jan Steen may have been stimulated by Frans Hals’s early genre works, as well as the large peasant scenes of Jacob Jordaens, who in the 1660s was working in Amsterdam for the new Stadhuis. This tendency reached its culmination in the As the Old Sing, So the Young Twitter (The Hague, Mauritshuis), a subject often painted by Jordaens. The works of Metsu, de Hooch and other painters active in nearby Amsterdam stimulated Steen in his Haarlem years to study the relation between figure groups and interior spaces, as can be seen in Easy Come, Easy Go (1661; Rotterdam, Mus. Boymans–van Beuningen), Twelfth Night (1662; Boston, MA, Mus. F.A.) and Take Heed in Times of Abundance (formerly dated 1663; Vienna, Ksthist. Mus.). As a rule, the smaller works of this period are undated, but the artist’s creativity and productivity must have been almost unlimited. He touched a wide range of subjects, treated them in highly original ways and never repeated himself. Most of his famous doctor’s scenes are from his Haarlem period, although he probably took up the subject much earlier. New in the iconography of his medical scenes is the fact that patients do not visit their physician, but he pays them a house call. The traditional ‘Dottore’ of the popular theatre is transformed into a family doctor, who most often does not recognize the true cause of the patient’s illness—invariably a young lady suffering from love sickness. Some of these works are inscribed Daar baat geen Medesyn Want het is minepyn (‘Here a physician is of no avail, since it is love sickness’; e.g. Munich, Alte Pin.).

It is difficult to form a coherent image of Steen’s production in the late 1660s. For whatever reasons, he began to experiment in widely differing directions. Some works hark back to the subjects and the style of Adriaen van Ostade, for example The School (Edinburgh, N.G.). The elegant companies in well-furnished interiors show the increased influence of Amsterdam, as in Backgammon-players (Amsterdam, Rijksmus.). In these works the light is softer and the colours are more subdued than in comparable paintings from previous decades. At the same time the number of biblical and mythological paintings began to increase, of which the absolute masterpiece is the Marriage of Tobias and Sarah (Brunswick, Herzog Anton Ulrich-Mus.). It is in the history paintings that Steen’s personal style and skill can best be seen, for instance his Samson and Delilah (1668; Los Angeles, CA, Co. Mus. A.), Iphigenia (1671; Amsterdam, Rijksmus.) and David with the Head of Goliath (1671; Copenhagen, Stat. Mus. Kst).

(c) c. 1670 and after.

With the exception of a few history paintings, there seems to have been a severe loss of quality around 1670, especially in the genre pieces. While Steen surely did not produce masterworks throughout his whole career, the existence of a number of weak paintings cannot be satisfactorily explained; for the moment these works of disappointing quality are dated c. 1670, when Steen returned to Leiden.

A surprising new development in the genre paintings—one that in many ways anticipated the Rococo—occurred with the Festive Company (1674; Paris, Louvre). The colours are bright and soft and the paint thinly applied in a very free, almost nervous movement of the brush. The scale of the figures is reduced and the interiors far more spacious. Good examples of this new trend are the Wedding Feast at Cana (1676; Pasadena, CA, Norton Simon Mus.) and the Feast in the Garden of the Paets Mansion (1677; ex-art market).

(ii) Subject-matter and sources.

Steen’s richly varied subject-matter centres around a few topics: family life and the education of children and adolescents; the follies of love; and varying forms of intemperance—drinking, squandering money, giving way to anger or lust. The painter often included inscriptions on his works (e.g. In Weelde Siet Toe: ‘Take heed in times of abundance’; De Wyn is een Spotter: ‘The wine is a mocker’; and Soo voor gesongen, soo na gepepen: ‘As the old sing, so the young twitter’ etc), but even where he did not, the moralizing intention is clear from the way he mocked the misbehaviour of his characters. Steen has rightly been praised for the characterization of the protagonists in his works and for the staging of his scenes. Both are aspects of his gift for storytelling. In his multi-figured compositions, gestures and glances link the individuals in an intricate network . These connections are so important that anatomical proportions or spatial relations are, when necessary, somewhat violated. In most cases, consequently, his figure groups are conceived as intricate configurations on the flat surface of the canvas or panel, much more than a number of spatial forms located in an imagined pictorial space. The spectator is compelled to see the attitude, gestures and facial expression of one of Steen’s figures together with the reactions they cause in face, limbs and body of one or more other figures. This effect reinforces or varies the characterization of standard types. It is never simply the character of ‘Dottore’ or ‘Capitano’—but ‘Dottore’ in the course of being deceived, ‘Capitano’ hesitating between the safety of fleeing and the danger of bluffing his adversaries into retreat. Most contemporary genre painters had a tendency to limit the figures in their works to no more than three, which severely restricted their dramatic possibilities.

Steen often found his inspiration in 16th-century prints, and deservedly he is often compared with Pieter Bruegel I. A popular, sometimes vulgar tone, complemented by an intentionally primitive style can be detected in aspects of the oeuvre of both masters. Steen’s figures are generally flat and strongly silhouetted in a way not unrelated to Bruegel’s Children’s Games (1560; Vienna, Ksthist. Mus.). Steen’s humour functions on two levels simultaneously. At first sight the comical effect seems to rely solely on overstatement: strong and schematic characterization, expressive and often grimacing faces and rhetorical gestures. At the same time, however, there are subtle innuendos and ambiguous hints in the narrative that create an amazingly wide margin for the spectator’s own interpretation. Thoré (see Bürger) was the first of many writers to compare the painter with Molière. Gudlaugsson pointed out how strong the affinity was between the popular theatre of the 17th century and Steen’s genre. Both art forms relied on psychological and social stereotypes cast in standard situations; this material was used in both media as an inexhaustible source for variation and improvisation.

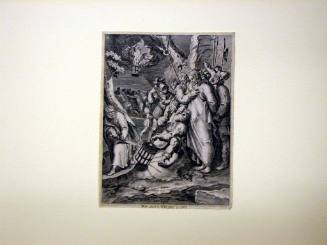

Steen’s few biblical and mythological subjects were sometimes treated as if they were genre subjects. He transplanted them to his own time and place so as to make the stories more accessible to his audience. In this respect he is the most direct 17th-century descendant of Lucas van Leyden and Pieter Bruegel. This intentional trespassing on the borderline between two pictorial traditions, genre and history painting, was often frowned on or misunderstood. Many considered it to show a lack of decorum aggravated by the mixture of theatrical and contemporary costume. Steen’s use of costume is not at all unusual when compared with the works of figure painters from the early 17th century. However, by the later years of the century history painters took more trouble to reconstruct period costume, whereas genre painters followed the latest fashions. The subjects and compositions of Steen’s biblical scenes were often inspired by prints from Pieter Lastman’s circle or by Rembrandt’s etchings. The Adoration of the Golden Calf (Raleigh, NC Mus. A.) is strongly reminiscent of Lucas van Leyden’s treatment of the same subject.

Steen made a very limited number of portraits, and these are remarkable because they do not follow any tradition. They seem to be ad hoc solutions, unrelated among themselves, created in the pictorial language of genre. The circle of his sitters may have been limited to his nearest relatives and friends.

(iii) Technique.

Steen has been seen by such authors as Thoré as a ‘literary’ painter, who was motivated by his desire to narrate and who adapted his style to the content of his stories. Thoré considered the style as well as the technique of Steen’s work to be the result of the fact that he painted rapidly, urged on by the multitude of ideas and images in his head. Certainly the literary element in Steen’s oeuvre is very strong; he was the only one in his generation to integrate explanatory texts into his paintings.

Steen’s use of colour is sometimes daring and often very subtle. His ‘strong and manly’ handling of the brush, admired by Reynolds, is not very elaborate but is very effective, creating the maximum of expressiveness with a minimum of labour. In the last phase of his development this ‘shorthand’ technique evolved into a virtuoso style of brushwork, which was quite unique in its period. Steen’s rendering of surface texture can be very convincing, but the treatment of details is restricted to passages where composition and narrative require objects to be brought to the viewer’s attention. The difference in execution between two separate works, and even within one single work, can be substantial. Steen’s contemporaries (e.g. ter Borch, van Mieris or Metsu) had a tendency to enhance the elegance and luxury of their subjects, by concentrating on the surface beauty of their works and a technical perfection of execution. This often involved a loss in the narrative and moralizing content of their paintings. Steen was their opposite in all respects. His rapid execution seems to have been rather careless in some cases, and many of his works have since suffered from overcleaning. His subjects, even his most well-bred companies, are always tinged with elements of low-life or petty bourgeoisie. Aesthetic concerns were never uppermost in his mind, and creating forms never became an end in itself. Steen did not master even the most basic rules of linear perspective, was careless about human anatomy and seems to have trusted to improvisation rather than careful planning in his compositions. The almost complete absence of drawings from Steen’s hand reinforces the impression that most of his paintings must have been executed directly on to the support.

3. Critical reception and posthumous reputation.

The first biography of Steen was written by Houbraken in 1718. The numerous anecdotes Houbraken told to demonstrate parallels between Steen’s life and his work have long determined the painter’s reputation and the interpretation of his work. He was believed to have been a drunkard, whose household was as dissolute as the ones he depicted and whose life style was reflected in his own low-life tavern scenes. Houbraken described the Marriage of Tobias and Sarah as if it were an ordinary genre scene; the author knew the painting well, because he had owned it himself, but the description of a biblical scene would have conflicted with his image of Steen as a painter who mirrored his own day-to-day surroundings in his art. Even more influential was the work of Houbraken’s imitator J. C. Weyerman, who paraphrased and embellished Houbraken’s biography of Steen. Weyerman added some spicy anecdotes and some reliable facts to Houbraken’s material, mentioned more paintings and described them correctly, but left out all discussion of art theory. The tenacious tradition initiated by Houbraken and Weyerman culminated in Heinrich Heine’s Aus den Memoiren des Herrn von Schnabelewopski, a book that is as valuable from a literary point of view as it is misleading art historically. It mistakenly contends, for instance, that Steen’s self-portrait, as well as the portraits of his first and second wife and of his children can be identified in most of his works. Bredius subsequently even tried to date Steen’s paintings by the age of the children depicted in them.

Sir Joshua Reynolds showed a strikingly independent judgement, admiring Steen’s artistic qualities (i.e. his technique, compositional skill and use of light and shade), although he thought his genre subjects were unworthy and his history pieces lacking in decorum. Steen and ‘others of the same school have shewn great power in expressing the character and passions of those vulgar people, which were the subjects of their study and attention. I can easily imagine, that … this extra-ordinary man…[could] … have ranged with the great pillars and supporters of our Art.’

Still valuable are the insights provided by Thoré, who stressed the literary content as well as the moral value of Steen’s works: ‘Mais ce terrible homme s’est souvent montré sous des aspects très-divers. Ses variations de manière tiennent à la variété des sujets. Son style et sa pratique se conforment toujours à la nature qu’il veut traduire.’ Parts of Steen’s work are completely realistic, and in other cases the painter ‘s’abandonne à une fantaisie de pratique aussi originale que la conception même des caractères, des physionomies, des attitudes’. Thoré considered Steen as a ‘mélange inexplicable de science et de licence, de profondeur et de frivolité; grand praticien, qui a ses défaillances; grand philosophe, et triple fou!’

Working in precisely the same years as Thoré but completely independently was the Dutch author van Westrheene. His goal was to restore the art of his own time by stimulating the study of well-chosen examples from the past. Dutch mid-19th-century artists should take the great masters of the 17th century as their guiding stars, and Steen had been one of the most important among them. This painter, however, could not serve van Westreheene’s didactic purposes, as long as he held such a controversial reputation. Therefore the author tried to prove, with the help of archival studies, that Steen had been misrepresented in earlier texts. Van Westrheene’s book on Jan Steen was one of the earliest monographic studies of a Dutch artist to include a catalogue raisonné of the oeuvre. Later attempts to improve Steen’s reputation, for instance by Bredius and Martin, were motivated even more by Dutch patriotism. Both made a great issue of whether Steen had been forced to marry Grietje van Goyen. In his numerous publications on Steen, Martin contributed to the painter’s popularity in the 20th century, abandoning the Steen created by Houbraken, Weyerman and Heine, although this was not replaced by a convincing new conception about the artist and his work). Much more influential has been later iconographical research on Dutch art, which has revived interest in moralizing messages. Since these publications often originated in the discipline of literary studies, they did not always pay enough attention to the specific way in which Jan Steen fused the artistic form and the literary content of his works. Sometimes he is represented as a stern moralizer, but this does no justice to his humour and wit, his exceptional place among his contemporaries and the pictorial qualities of his works. Others still hold the opinion that moralistic messages were a mere pretext for Steen to ridicule his philistine patrons, to follow his painterly instincts and to give way to his undisciplined humour. It is a tenacious misunderstanding that moral admonition and humour are mutually exclusive. Both are represented in Steen’s oeuvre on a high level and in a very personal, inextricable combination.

Lyckle de Vries. "Steen, Jan." In Grove Art Online. Oxford Art Online, http://www.oxfordartonline.com.proxy.lib.fsu.edu/subscriber/article/grove/art/T081140 (accessed May 8, 2012).

Person TypeIndividual