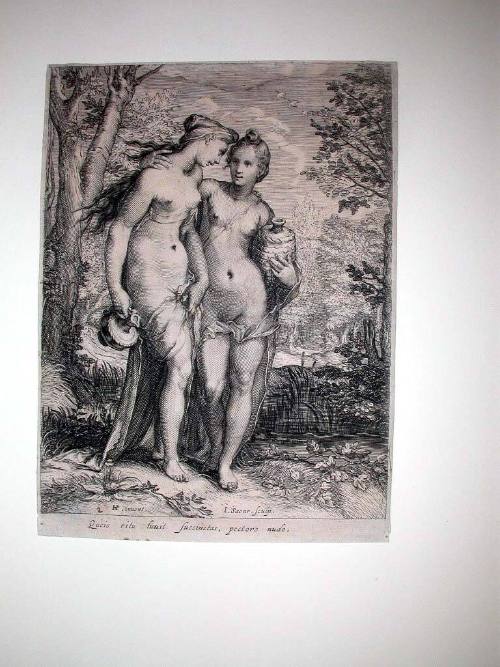

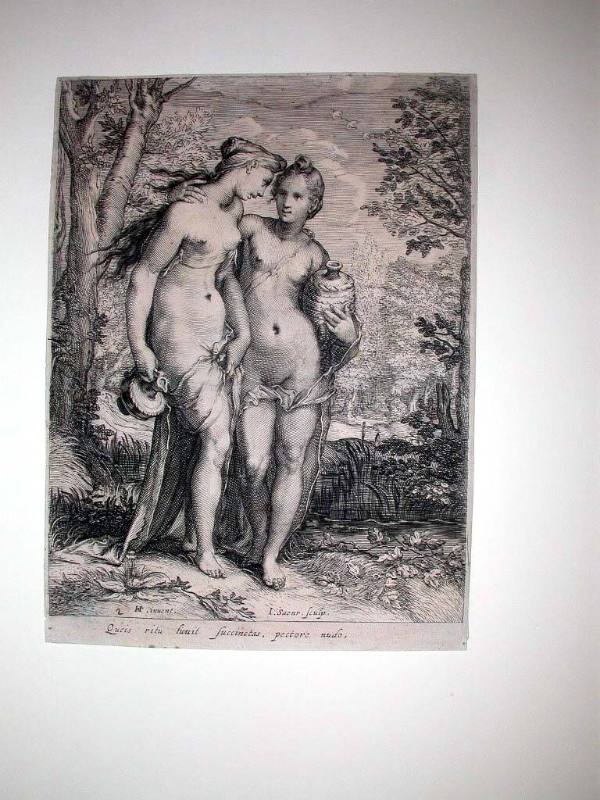

Pieter Saenredam

Dutch, 1597-1665

Painter and draughtsman, son of Jan Saenredam. His paintings of churches and the old town halls in Haarlem, Utrecht and Amsterdam must have been appreciated by contemporary viewers principally as faithful representations of familiar and meaningful monuments. Yet they also reveal his exceptional sensitivity to aesthetic values; his paintings embody the most discriminating considerations of composition, colouring and craftsmanship. His oeuvre is comparatively small, the paintings numbering no more than 60, and each is obviously the product of careful calculation and many weeks of work. Their most striking features, unusual in the genre, are their light, closely valued tonalities and their restrained, restful and delicately balanced compositions. These pictures, always executed on smooth panels, are remarkable for their sense of harmony and, in some instances, serenity. Here, perhaps, lies a trace of filial fidelity to the Mannerist tradition of refinement and elegance, of lines never lacking in precision and grace. But Mannerist figures and the more comparable components of strap- and scrollwork embellishment lack the tension and clarity of Saenredam’s designs, which also have a completeness reminiscent of the fugues of Gerrit Sweelinck (1566–?1628).

1. Life and work.

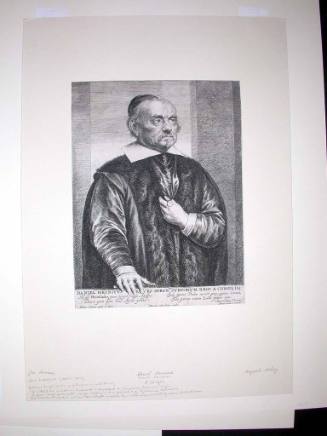

Pieter Saenredam’s widowed mother moved to Haarlem in 1609, two years after her husband’s death, and in May 1612 assigned her son, then 15, to the workshop of Frans de Grebber (1573–1649), one of a circle of Haarlem painters whose styles adhered to the ‘classical reform’ of the early Baroque period. Until he joined the Haarlem Guild of St Luke on 24 April 1623, Saenredam stayed in de Grebber’s studio. Eleven years was an exceptionally long time to serve as an apprentice and, presumably, assistant. This may perhaps be explained in part by the artist’s physical condition: as seen in a portrait drawing (1628; London, BM) by his friend and fellow pupil the architect Jacob van Campen, Saenredam was stunted in stature and apparently hunchbacked, which might have made him somewhat reclusive.

Saenredam’s activity until 1628, the date of his first painting, the Interior View of St Bavo’s, Haarlem (Malibu, CA, Getty Mus.), can barely be accounted for by the drawings he made c. 1627 to be engraved (by Willem Ackersloot) for Samuel Ampzing’s Beschryvinge ende lof der stad Haerlem (Haarlem, 1628) and those designs for independent prints, such as the Siege of Haarlem (1626) by Cornelis van Kittenstein (c. 1600–after 1638). In view of Saenredam’s evident command of linear perspective by 1628 and the professionally produced ground-plans and elevations dating from a few years later (e.g. two copies of Salomon de Bray’s Design for Warmond Castle, 1632; Haarlem, Gemeentearchf), it is possible that he had already worked as an architect’s draughtsman, perhaps with de Bray or van Campen. Saenredam’s use of perspective, in any case, was consistently more sophisticated than the procedures, usually little more than patterns, that contemporary painters such as Pieter Neeffs adopted from perspective treatises. This expertise was instrumental in Saenredam’s subsequent depictions of actual architecture. His early experience in oil painting must also have been more extensive than previously recognized, for his pictures of 1628 and the next few years are not in any way naive. The most plausible candidates for early pictures are small-scale portraits, like those recorded in Saenredam’s early drawings and prints. These painted portraits would have been of the type that Frans Hals occasionally and later Gerard ter Borch —and coincidentally the church painter Emanuel de Witte—executed on the scale of engravings. What is consistently evident in all of Saenredam’s early known work—the drawings of people and plants, the maps, the landscape drawings with ruined castles, and the interior and exterior views of St Bavo’s made for Ampzing’s book—as well as in his subsequent drawings of architectural views (for illustration see Album), is the artist’s high regard for exact appearances. For Saenredam, the function of drawing was to record, not to invent. Such a documentary approach was not unknown in the Goltzius circle (to which Pieter’s father Jan belonged), but it finds closer parallels in the work of younger artists such as Esaias and Jan van de Velde, Hendrick Vroom and Jacques de Gheyn II.

For the first eight years of his career as an architectural painter (1628–36), Saenredam devoted most of his attention to the interior of St Bavo’s in Haarlem. Three paintings depict extensive views of the building, that dated 1628 (Malibu, CA, Getty Mus.), representing nearly all of the transept and the open spaces around the crossing, the others surveying the length of the church to the east (?1628; Philadelphia, PA, Mus. A.; corresponding to the plate in Ampzing, 1628) and to the west (1635; Edinburgh, N.G.), the latter being perhaps his most ambitious work. Other panels depict a view from the choir to the Brewers’ Chapel (1630; Paris, Louvre); the southern aisle (1633; Glasgow, A.G. & Mus.); the southern ambulatory (1635; Berlin, Gemäldegal.); and five views across the choir (1635, Warsaw, N. Mus.; 1636, Amsterdam, Rijksmus.; Paris, Fond. Custodia, Inst. Néer.; Zurich, Stift. Samml. Bührle; and 1637, London, N.G.). A view of the Brewers’ Chapel was also the setting for religious figures (as in the Presentation in the Temple, 1635; Berlin, Gemäldegal.), serving as what would too dismissively be described as staffage. This first and, remarkably, only series of paintings depicting St Bavo’s (the subject, so closely associated with Saenredam’s name, was not treated again for another 25 years) exhibits a characteristic attempt to record each interesting view in the church, without repetition, and a similarly comprehensive plan to explore the potential of various compositional ideas (e.g. long recessions along elevations; views across elevations with framing motifs in the foreground; elevations with no repoussoirs). Curiously, the only later painting of the Interior of St Bavo’s (1660; Worcester, MA, A. Mus.) is a wide-angle view of the choir, which seems to complete Saenredam’s survey of the site.

Saenredam also recorded sites outside Haarlem, for instance the St Pieterskerk in the newly captured town of ’s Hertogenbosch (1632; London, priv. col., see Schwartz and Bok, fig.), where his uncle (and presumed host), the Revd Johannes Junius, who had moved there from Assendelft in February 1631, was minister. On the same trip in July 1632, Saenredam made a sketch (London, B.M.) of the choir of the great Gothic cathedral of St Jan and the monumental rood-screen (1611–13; London, V&A). In the later painted view (1646; Washington, DC, N.G.A.), Saenredam inserted the altarpiece by Abraham Bloemaert (Paris, Louvre) that had already been removed or covered by the Dutch when he drew the site. Here and in the careful drawings of the rood-screen and the tomb of Bishop Gisbert Masius (’s Hertogenbosch, Noordbrabants Mus.), Saenredam seems to have been consciously recording for posterity, and in many cases architectural historians are indeed indebted to him: the St Pieterskerk at ’s Hertogenbosch, for example, was destroyed in 1646.

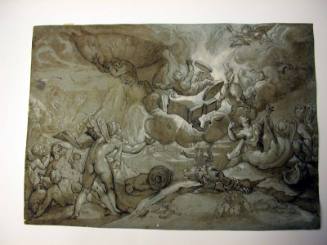

The most productive of Saenredam’s sojourns away from Haarlem was spent in Utrecht from June to October 1636. Bloemaert’s busy studio was probably open to the Haarlem artist, since his father had been one of the celebrated Utrecht master’s leading engravers. The first and most extensive series of sketches made in Utrecht are of the St Mariakerk (destr.); after a month of regular work on sketches of both the interior and exterior of that imposing Romanesque monument (e.g. Utrecht, Gemeentearchf; Haarlem, Teylers Mus.; Rotterdam, Mus. Boymans–van Beuningen), Saenredam turned to the other churches of Utrecht, the Buurkerk (see figs 1 [not available online] and 2 [not available online]) and the St Jacobskerk in August, the St Janskerk and the cathedral (see [not available online]) in September and October and finally the St Catharinakerk. In each case, the fully dated drawings reveal that Saenredam proceeded from principal to subordinate views. The first paintings derived from the Utrecht portfolio represent the St Mariakerk and form a consistent group: two paintings dated 1637 (Amsterdam, Rijksmus., and Kassel, Schloss Wilhelmshöhe), two of 1638 (Brunswick, Herzog Anton Ulrich-Mus., and Hamburg, Ksthalle), two minor works of c. 1638–40 (Amsterdam, Rijksmus., and Utrecht, Cent. Mus.) and the large panel dated 1641 (Amsterdam, Rijksmus.), Saenredam’s second most ambitious work. The chronology and the number of sketches and finished paintings support the hypothesis (see Schwartz, 1966–7) that Saenredam’s trip to Utrecht depended on Constantijn Huygens the elder’s interest in the St Mariakerk and other examples of Romanesque architecture. Huygens, artistic impresario and private secretary to the Dutch Stadholder, was known to Saenredam through his staffage painter Pieter Post, who was also Huygens’s architectural protégé. Two of the Mariakerk paintings, those of 1637 and 1641 (both Amsterdam), the latter with figures by Post, once hung in Huygens’s house in The Hague.

Saenredam married in December 1638 and thereafter stayed mostly in Haarlem; in 1640 he was named steward and in 1642 dean of the painters’ guild there. Apart from the meticulous drawing, dated 15–20 July 1641, of the Old Stadhuis, Amsterdam (Amsterdam, Gemeentearchf; painted version, 1657; Amsterdam, Rijksmus.), the next evidence of Saenredam’s activity outside Haarlem is found in drawings (e.g. Haarlem, Teylers Mus., and Amsterdam, Rijksmus.) from July 1644 of the Koningshuis, the palace (built 1630–31) of the ‘Winter King’ Frederick V of Bohemia, and the St Cunerakerk at Rhenen. Huygens and the designer of the Koningshuis, Bartholomeus van Bassen (who was court architect in and around The Hague), were probably responsible for Saenredam’s interest in the subject. Similarly, the new subjects of Saenredam’s later years—the Nieuwe Kerk in Haarlem (drawings, 1650 and 1651; Haarlem, Gemeentearchf) and the Grote Kerk at Alkmaar (drawings, May 1661; Vienna, Albertina, and Berlin, Kupferstichkab.)—involve a building and church furniture designed by his associate Jacob van Campen. It would be mistaken, however, to imagine Saenredam’s subjects were assigned to him by others. His like-minded colleagues provided him with opportunities to pursue his profound interest in architecture and its representation: thus the St Mariakerk in Utrecht, for example, led the artist to depict every other church in town and to produce independent pictures from 1637 to nearly the end of his life (e.g. the Mariaplaats and the St Mariakerk from the West, 1663; Rotterdam, Mus. Boymans–van Beuningen).

2. Working methods and technique.

Most of Saenredam’s oeuvre can be divided into one of three categories: on-site sketches (i.e. ‘from life’), construction drawings and finished paintings. These present few problems of chronology, for the artist was devoted to documentation, inscribing almost all of his material with dates (to the day) and keeping it on file. A good example of this methodical approach is the series of views of the Interior of the St Odulphuskerk, Assendelft. The on-site sketch (Amsterdam, Hist. Mus.) is dated 31 July 1634, and the corresponding construction drawing (The Hague, Rijksdienst Mnmtzorg) bears two sentences in Saenredam’s handwriting describing the subject (including the remark ‘Assendelft, a village in [the province of] Holland’) and giving the date as the ‘9th day of December in the year 1643’. There then follows in different ink and larger letters: ‘This was painted on the same scale as this drawing, on a panel of one piece, and the painting was finished on the 2nd day of the month October in the year 1649, by me Pieter Saenredam.’ Finally, the painted panel (Amsterdam, Rijksmus.) is inscribed ‘this is the church at Assendelft, a village in Holland by Pieter Saenredam, this painted in the year 1649, the 2nd October’. In the foreground of the picture is a tombstone inscribed, in Latin, ‘Jan Saenredam famous engraver’.

Such a systematic approach differed greatly from the working methods of most contemporary architectural painters. The majority of those active c. 1550–c. 1650 evidently composed their underdrawings on the panel itself, whereas Saenredam used construction drawings, which were drawn on cream-coloured paper, blackened on the verso and then traced on to the prepared panels. Saenredam’s construction drawings are further distinguished by the fact that they incorporate and modify all the information found in the on-site sketches. These sketches confronted problems of design that were rarely, if ever, addressed by other architectural painters, either those active before Saenredam or those, such as Gerard Houckgeest, Hendrick van Vliet and Emanuel de Witte, who were active in Delft from 1650 onwards.

Saenredam, unlike others, accepted the terms dictated by the actual viewing situations: a close vantage point, consequently wide-angle views and fragmentary arrangements of architecture. Parallel developments are evident in Haarlem in other genres; Jan van Goyen’s landscapes and Pieter Claesz.’s still-lifes, for example, move in much closer to their subjects than would comparable works by an older artist. The subject of the church interior brought with it unique dilemmas of design, but extensive evidence suggests that Saenredam fully understood the practice of artificial perspective and was well aware of the differences between looking at architecture in the round and transcribing it on to a flat surface. His on-site sketches of church interiors usually bear a circled dot and even a measurement indicating the vanishing-point, which in the underdrawing of a corresponding painting occurs in the same place. However, the sketches were made without the help of a straightedge or a system of orthogonals, and Saenredam paid only scant attention to his vanishing-point as he looked in many directions, which together considerably exceeded the angles of view recommended in perspective treatises of the period. Only a camera with a wide-angle or ‘fish-eye’ lens could record the subjects found in most of Saenredam’s paintings, but the distortions he allowed (being free of unwonted curves) are comparable to the contemporary Mercator projection, a system of representation used in mapmaking. While the marginal distortions and overall fanning effects of a typical Mercator projection were potentially very troublesome to Saenredam (whose subject was structured by regular solids such as columns spaced at constant rather than increasing intervals), he turned this inherent perspective problem into a principle of design. His paintings are not at all illusionistic, nor are they realistic in the same way as his drawings made ‘from life’. The degree of stylization or abstraction in many of his finished pictures is more akin to that of the mapmaker, the architect or the marquetry designer.

3. Critical reception.

The sophisticated and abstract character of Saenredam’s paintings is a feature that appeals more to the modern mind than it would have to all but a few of the painter’s contemporaries. What is now regarded as exquisite subtlety in Saenredam’s work might have been appreciated, if at all, as an appropriate sobriety by viewers of the time, some of whom had seen St Bavo’s walls and columns stripped of their ‘Popish’ appointments and whitewashed. Only in hindsight is it clear that Saenredam’s sense of refinement and his spirit of reform (he tended to temper Gothic arches and to omit decorations that the Calvinists had left behind) are contradictions characteristic of this conflict-ridden period, like those of the black Dutch dress, derived from Spanish court costume, which was (when well tailored) at once elegant and reserved.

Saenredam’s eccentric, if orthodox, use of perspective to stylize the image was not a programme that other artists could easily adopt, especially if, as in Delft, the illusion of three-dimensional space was a primary goal. Thus he had no real followers, though his compositions occasionally influenced other artists, especially the Haarlem painters Gerrit Berckheyde and Isaac van Nickele ( fl 1659–1703). The significance of Saenredam’s achievement exceeds his importance for a single genre of painting: he demonstrated, like Vermeer and other Dutch painters of exceptional ability, that perception is always subjective, that art is more than a mirror of reality. Architecture, in Saenredam’s selective view, is not a subject found in nature, but an expression of the human spirit, another art form.

Dorothy Limouze and Walter Liedtke. "Saenredam." In Grove Art Online. Oxford Art Online, http://www.oxfordartonline.com.proxy.lib.fsu.edu/subscriber/article/grove/art/T074922pg2 (accessed May 8, 2012).

Person TypeIndividual