Bartolomeo Manfredi

Italian, c. 1580-1620/21

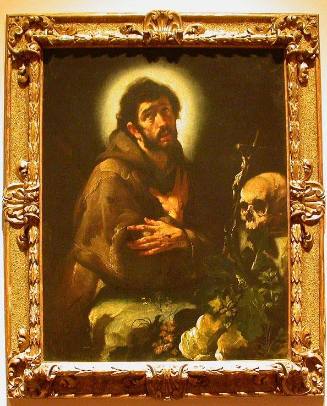

Italian painter. In the 17th century he was known throughout Italy and beyond as Caravaggio’s closest follower and his works were highly prized and widely collected. More than simply aping Caravaggio’s style, Manfredi reinterpreted his subjects and rendered new ones, drawing upon Caravaggio’s naturalism and dramatic use of chiaroscuro. His paintings were often praised by his contemporaries as equal to Caravaggio’s and he was subsequently emulated and imitated by other Roman Caravaggisti during the 1610s and 1620s. Yet by the 18th century his works were forgotten or confused with those of Caravaggio himself, and he is today among the most enigmatic Italian Baroque painters.

He learnt the principles of painting in Milan, Cremona and Brescia, and moved to Rome probably c. 1605, perhaps earlier (Mancini). There he studied with Cristoforo Roncalli (Baglione) and may have been Caravaggio’s assistant, although this seems unlikely since Caravaggio strongly objected to imitators, and Manfredi’s biographers would probably have related such important information. He is first documented in Rome in 1610, and his name appears frequently in parish records until 1622, often with those of his servants and assistants. He apparently never inscribed his paintings; no work displays his signature or a date, and no evidence such as contracts or letters related to extant paintings by Manfredi, or records of payments to him, is known. Efforts to identify his pictures are further complicated by the broader problem of discerning individual hands among the Caravaggisti. It is therefore difficult, if not impossible, to construct a strict chronology for his paintings, although his general development is distinguished by a progression away from Caravaggio’s artistic ideals towards a more personal artistic conception.

Bartolomeo Manfredi: Bacchus and Drinker, oil on canvas, 1.32×0.96 m…The early period, from which few originals survive, is the most problematic. It is the least documented phase, and there are numerous copies and variants of lost compositions. Yet a small, varied group of works reveal, in their sharply defined forms and choice of subjects (allegories, mythologies and genre scenes), his close and direct dependence on Caravaggio’s youthful paintings. The Chastisement of Cupid (Chicago, IL, A. Inst.), which was probably painted c. 1607, is thought to be Manfredi’s earliest extant painting. Its bright, saturated colours and sharply defined forms are characteristic of late Roman Mannerism. The dramatic composition, violent action and strong chiaroscuro, however, betray Manfredi’s knowledge and mastery of Caravaggio’s tenebrism (seen for example in the latter’s Martyrdom of St Matthew; Rome, S Luigi dei Francesi). A physiognomic type that appears in the Chastisement remained virtually unchanged throughout Manfredi’s career: figures with oval faces, broad noses, flaring nostrils and full lips, heavy, puffy eyes, and pronounced brows and chins. These features generically reveal Manfredi’s interest in Caravaggio’s early secular paintings, such as his Concert of Youths (New York, Met.). Manfredi’s lost Allegory of the Four Seasons (ex-Scialiapin Col., Paris; see 1987 exh. cat., p. 62), known through an excellent copy (Dayton, OH, A. Inst.), also dates from his early career, as does the Bacchus and Drinker (Rome, Pal. Barberini). In all of these the figures are shown in rather shallow, confined interiors, an element found in all of Manfredi’s works. The space is defined by raking light and a dark background wall.

In Manfredi’s mature period the variety of compositional schemes yielded to much more regular, formulaic and frieze-like compositions with half-length figures, and he adopted themes foreign to Caravaggio’s oeuvre, such as tavern scenes. The brilliantly contrasting colours and clear light of his youthful works were replaced by a limited palette of warm colours and by moist, atmospheric effects. The start of this period is marked by his Assembly of Drinkers (c. 1610; priv. col., on dep. Los Angeles, CA, Co. Mus. A.), based on Caravaggio’s Calling of St Matthew (Rome, S Luigi dei Francesi) in which a group of half-length figures is shown seated at a table in a shallow space defined by chiaroscuro. The palette is sombre, although the horizontal composition is animated by the staccato organization of expressive hands and tilted heads. His depictions of carefree gatherings of merrymakers greatly inspired other Caravaggisti. Foreign painters in particular recognized Manfredi’s skill at capturing human nature through direct observation and at portraying everyday events with uncommon sensitivity—what Sandrart called the ‘Manfrediana methodus’. Many of his subjects were strictly secular. Unlike Caravaggio, his work is more decorative than didactic. The symmetrical, isocephalic composition of the Concert and Card Players (c. 1612; Florence, Uffizi; both destr. 1993) is typical of the painter’s fully developed method of spatial organization. The brushwork is generally freer, the colours darker and the paint more liquid than in earlier works.

Although Manfredi is known primarily for his depictions of secular subjects, he also executed numerous private religious paintings. These he often cast in the guise of genre scenes. He painted several versions of Christ Crowned with Thorns (one example, Springfield, MA, Mus. F.A.). The Christ Driving the Money-changers from the Temple (c. 1613; Libourne, Mus. B.-A. & Archéol.), which contains an architectural setting and a dramatic group of fleeing figures indebted to Caravaggio’s Martyrdom of St Matthew, served as a source for Valentin de Boullogne, Cecco del Caravaggio and Theodoor Rombouts, among others.

Manfredi was highly successful, according to Mancini, and some of the most important collectors in Rome and Tuscany owned his works, among them Vincenzo Giustiniani and Ferdinando I de’ Medici. Mancini also relates that the Accademia dei Pittori in Florence requested Manfredi’s portrait. Although his biographers state that he executed a small number of public works, none is recorded in Roman guide books. By 1615 his fame had spread beyond central Italy. In that year, Giulio Cesare Gigli’s poem La pittura trionfante (published in Venice) briefly mentions Manfredi.

His last phase reveals an expressive, freer use of paint and more rapid brushstroke that was inspired by his awareness of Caravaggio’s late, more broadly executed paintings. Compositionally and technically the Tribute Money (c. 1618; Florence, Uffizi) is indebted to the Tooth-puller (Florence, Depositi Gal.), now thought by many scholars to be a late work by Caravaggio himself rather than by one of his followers. Manfredi may have seen this painting on an unrecorded trip to Florence. In the Christ Appearing to the Virgin after the Resurrection (c. 1621; Florence, Gregori priv. col.; see 1987 exh. cat., p. 85), probably the artist’s last known picture, his freer style is most evident. Passages of heavy impasto and thinly brushed areas of paint enliven its surface. The highlights are dull and the flesh unnatural and waxy; the quickly painted, ‘disjointed’ figures of Christ and the Virgin are also remarkable for being full-length and life-size.

Although Baglione lists Manfredi’s name among notables who died during the papacy of Paul V (1605–21), a notice of Manfredi’s death is dated 12 December 1622. Joachim von Sandrart was the first writer to recognize that Manfredi himself initiated an independent and flourishing form of Caravaggism. In his Teutsche Academie, he used the term ‘Manfredi Manier’ to describe the paintings of the Flemish artist Gerard Seghers. He also wrote that Nicolas Régnier worked in the ‘methodum’ of Manfredi, and that Valentin was a follower of Caravaggio and Manfredi. No works can be certainly assigned to Manfredi’s known assistants. Though no documentary evidence connects them, the earliest extant works of Régnier and Nicolas Tournier come so close to Manfredi’s style that it is likely that they studied with him.

John J. Chvostal. "Manfredi, Bartolomeo." In Grove Art Online. Oxford Art Online, http://www.oxfordartonline.com.proxy.lib.fsu.edu/subscriber/article/grove/art/T053775 (accessed April 11, 2012).

Person TypeIndividual