Jusepe de Ribera

Spanish, 1591 - 1652

Jusepe de Ribera was of humble origins and is believed to have been the son of a shoemaker. At a young age he went to Valencia to study at the studio of F Ribalta who was one of the first artists - along with Navarrete - to introduce the tenebrism of Caravaggio to Spain. Ribera learned a great deal from Ribalta, perfecting his draughtsmanship and precision of detail. He soon left for Rome where he studied the great masters Michelangelo and Raphael, though the work of Caravaggio remained his main inspiration. Much has been written about the time Ribera spent in Rome: impoverished and dressed in rags he was taken in as a servant by a cardinal in the city but fled the cleric's house, preferring to live the life of a painter. In fact it is more likely that Ribera was influenced by Caravaggio, although they could barely have coincided since when Caravaggio died in 1609 after years of exile, Ribera was only 21 years old.

Following Caravaggio's death, Ribera went through a period of indecision. He went to Parma to study Correggio; however, it appears that the grace and charm characteristic of Correggio's style, albeit tempered by a certain plenitude and solidity, was ill-suited to the contrary nature of Ribera who continued to prefer the grace and sensuality of Caravaggio.

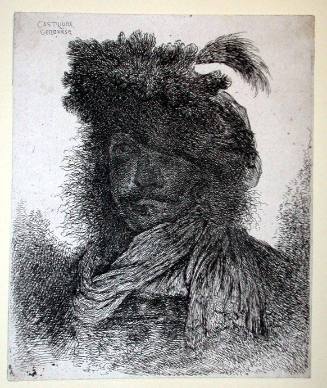

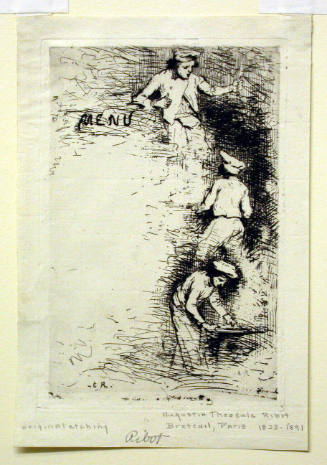

After this period in Parma, Ribera went to Naples and settled there in 1616. Once again, biographers recount details of his life that appear to come straight out of a picaresque novel: intrigues, poisonings, rivalry, disturbances and dramas of all kinds - but this went hand in hand with a remarkable society life. After the poverty came wealth and fame - fame because at that period Naples was a dependency of Spain and therefore welcomed Ribera with open arms. He soon gained the protection of the Duke of Osuna, Viceroy of Naples who, excited by Ribera's work, sent some of his paintings back to Spain. The painter's fame rapidly spread to the country of his birth. He continued to enjoy the protection of the various viceroys of Naples and began to lead a society life, being appointed court painter and living at the palace. He also made a very advantageous marriage. Now that he was famous, Ribera began to receive visits from his compatriots: in 1626 it was the turn of Jusepe Martinez; in 1629 and in 1649 he received visits from Velázquez whom the king had asked to bring back a selection of Ribera's work for the Escorial. In 1626 the pope conferred the Order of Christ on the artist and in 1630 he was admitted to Accademia di San Luca in Rome. Ribera continued to enjoy great success right up to the end of his life. He also had a number of pupils who imitated him, some of whom effectively plagiarized his work - Luca Giordano, one of his most gifted pupils, was among the most adept at this. Ribera had a considerable influence that continued on through Romanticism and Realism. Ribera's Elements of Drawing were turned into etchings by Francisco Fernandez for the instruction of young painters and Ribera himself made 26 etchings. In 1648 the pope awarded him the habit of the Military Order of Christ. Though covered in glory, the end of the artist's life came under a cloud when the people of Naples rose up against the Spanish under the leadership of Masaniello. Ribera must have been on good terms with Don John of Austria (also known as the Lesser or bastard son of Philip IV) who suppressed the rebels and whose portrait the artist painted in 1648. Legend has it that Don John seduced Ribera's daughter and abandoned her at the age of 16, leaving her the mother of a baby girl and that as a result she entered a convent in 1666.

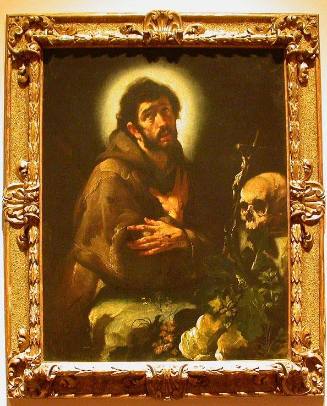

During his first period, between approximately 1620 and 1630, Ribera worked in a sombre style, not only in terms of his choice of colour but also in his choice of religious subjects. He suddenly developed a taste for scenes of martyrdom, accentuating the suffering of whichever saint was concerned and sparing no detail - he was first and foremost a painter of reality but in a very Spanish religious context. He also painted down-and-outs, old people and invalids. The French poet and critic Théophile Gautier celebrated Ribera's work in this verse: 'As another seeks beauty, you seek to shock - martyrdom, executioners, gypsies, down-and-outs - displaying an open sore alongside some rags'. However, he continued to receive plenty of commissions. The Duke of Osuna commissioned him to produce a retable for his collegiate church, which Ribera executed between 1616 and 1620; the Jesuits commissioned several works for the monastery of S Francis Xavier. From 1628 to 1631 he painted a St Sebastian Ministered to by Irene (at the Hermitage), which reveals a morbidity associated with the subject which borders on the erotic; his Martyrdom of St Andrew (Budapest, 1630) dates from approximately the same period.

Ribera gave expression to a violent but above all physical faith; he liberated Spanish painting from its tendency towards a classical Italianized style, yet without producing the revolution that Ribalta had in fact started. Jacques Lassaigne describes Ribera as 'a brutal revolutionary, a rebel yet a great classic'. The artist was also capable of introducing a certain tenderness into some of his mystical compositions, as can be seen in Jacob and Laban's Flock (1634). However, the series of paintings of philosophers and mythological scenes he executed provided another opportunity to explore new examples of torment, as in Prometheus and Ixion and Apollo and Marsyas. He depicts his philosophers as inveterate drinkers or tramps; only Archimides, dating from around 1630, who appears as a smiling old man with calloused hands, is spared and is the least depraved of the series. This composition is based around a sort of still-life formed by the book and paper used by the learned man.

After 1635, Ribera's work became less sombre, his compositions grew lighter and less constricted, the effects he used less brutal. He appeared to be seeking a new way forward, far more so than in the previous period, when his style seemed to be firmly established. His St Anthony of Padua and the Christ Child (1640) is suggestive of Zurbarán and Murillo and his Venus and Adonis of Guercino. The new qualities of Ribera's style are often associated with the fact that he presents his subjects in the open air. And although his themes remained largely the same - continuing his predilection for martyrs and physical anomalies - he succeeded in creating such remarkable pieces as The Club-Footed Boy (now in the Louvre). His masterwork of this period, and perhaps indeed of his entire oeuvre is Jacob's Dream (1639) - a work executed without excess but with intense gravity in which, for once, a supernatural light appears to shine through with great subtlety. The old man is sleeping against a landscape reduced to just sky; the piece reveals a concern for truthfulness, a gentle light from the heavens illuminating the subject's face and hands. Ribera adheres to these qualities of precision and restraint when depicting figures who are dead or melancholic figures such as the Virgin in the Metropolitan Museum of New York. The Martyrdom of St Bartholomew, on the other hand, although set in the open air, retains a theatricality of composition in which the martyr's suffering is glorified and the brutal force of the executioners accentuated. However, the eyes of St Bartholomew are shown in ecstasy, lending a certain pathos to the piece. This work was painted between 1630 and 1639, which explains why it reflects both the main tendencies of Ribera's work.

Like Poussin and Lorraine, Ribera spent his entire working life in Italy; all his paintings were executed there; he studied the Italian masters in depth; and yet he retained his own nature and individuality. Born in Spain, he remained intrinsically Spanish and the austerity of his art ties him to the country of his birth. Moreover, he was proud of this and always made a point of adding the word 'Spaniard' to his signature. Ribera was first and foremost a realist, in the sense that the exaggeration of aspects of everyday life continues to be termed realist, while his theatricality led him to carry to extremes the contrast between light and shade. He also sought out subjects that were of striking or even hideous appearance, painting heads of bald and bearded old men, for example. And to display his knowledge of anatomy to its full he sought out decrepit, emaciated bodies, wrinkled, calloused hands. He displayed an attachment to the most frightful of subjects and the most brutal and hideous of details, carrying emotion into the realms of horror and dread.

"RIBERA, Jusepe de." In Benezit Dictionary of Artists. Oxford Art Online, http://www.oxfordartonline.com.proxy.lib.fsu.edu/subscriber/article/benezit/B00151925 (accessed April 16, 2012).

Person TypeIndividual

Italian, c. 1610 - 1665