Gerrit van Honthorst

Dutch, 1592 - 1656

Dutch painter and draughtsman. He came from a large Catholic family in Utrecht, with several artist members. His grandfather, Gerrit Huygensz. van Honthorst ( fl c. 1575–9), and his father, Herman Gerritsz. van Honthorst ( fl c. 1611–16), were textile and tapestry designers (kleerschrijvers); his father is also occasionally mentioned in documents as a painter. Both his grandfather and father held official positions in the Utrecht artists’ guilds, Gerrit Huygensz. from 1575 to 1579, and Herman Gerritsz. in 1616. Two of Gerrit Hermansz.’s brothers were also trained as artists. Herman Hermansz. van Honthorst ( fl 1629–32) was trained to be a sculptor but later became a priest, and Willem Hermansz. van Honthorst (1594–1666) studied painting under Gerrit Hermansz., whose style he frequently emulated. Gerrit Hermansz. was the most successful artist in the family and the most famous member of the group of Utrecht caravaggisti, the Dutch followers of Caravaggio. His predilection for turning the great Italian painter’s dramatic patterns of natural light and shadow into nocturnal scenes with cleverly rendered effects of artificial illumination won him the Italian nickname ‘Gherardo delle Notti’.

1. Life and work.

(i) Training and visit to Italy, before mid-1620.

Gerrit trained as a painter in the Utrecht studio of Abraham Bloemaert. He must have travelled to Italy between c. 1610 and 1615. It is probable that he arrived closer to 1610, given his numerous surviving Italian period commissions and the fact that he attracted the attention of such important Roman art patrons as Vincenzo Giustiniani, in whose palace he lived, Scipione Borghese and, in Florence, Cosimo II de’ Medici, Grand Duke of Tuscany. According to the Italian art critic Giulio Mancini, who included a biography of van Honthorst in his Considerazioni sulla pittura (Rome, c. 1619–20), the young artist attended an academy for life drawing in Rome, a fact confirmed by a dated drawing of a Male Nude (1619; Dresden, Kupferstichkab.). Mancini also mentioned several paintings by him with unusual light effects. These include a Nativity (1620; Florence, Uffizi), painted for Cosimo II, with the light source emanating from the Christ Child, and the important altarpiece of the Beheading of St John the Baptist, painted for the church of S Maria della Scala, Rome (1618; in situ), in which the scene is illuminated by torchlight. The masterpiece of van Honthorst’s Roman period, Christ before the High Priest (c. 1617; London, N.G.), painted for Giustiniani, using a candle as light source, has been praised as an anticipation of Rembrandt’s psychological insights, as well as of the works of Georges de La Tour. Not all of van Honthorst’s Italian works employ artificial lighting; some, such as the striking Liberation of St Peter (c. 1616–20; Berlin, Bodemus.), also painted for Giustiniani, use the dramatic raking daylight often found in Roman period paintings by Caravaggio, for example the influential Calling of St Matthew (Rome, S Luigi dei Francesi), in which the light enters the composition from the right as it does in the van Honthorst painting.

(ii) Utrecht, mid-1620–28.

In spring 1620 van Honthorst, together with another artist, one of the Colijn de Nole family of sculptors from Utrecht, left Rome for the northern Netherlands. His homecoming was celebrated on 26 July at the inn ‘De Poortgen’ in Utrecht, owned by his future mother-in-law, Bellichgen van Honthorst, a distant relative. The event was recorded in the diary of the Utrecht scholar Arnhout van Buchell; among those present were the painters Abraham Bloemaert and Paulus Moreelse, the engraver Crispijn de Passe I, the sculptors Robrecht (d 1636) and Jan (d 1624) Colijn de Nole and the artist and dealer Herman van Vollenhoven ( fl 1611–27). In October of the same year van Honthorst married Sophia Coopmans, the daughter of a wine merchant. Several members of the Coopmans family, including Sophia’s brother Dominicus, were artists. Soon after their marriage the van Honthorsts took up residence in a house on the Snippevlucht, a small street in the centre of Utrecht where Hendrick ter Brugghen also lived. It is uncertain, however, if the two artists were actually neighbours as it is not possible to document ter Brugghen’s residence on the Snippevlucht until 1627, the year van Honthorst moved to another part of Utrecht.

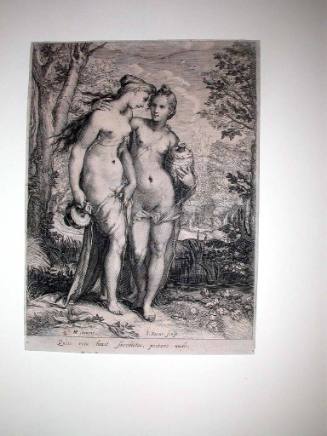

In 1622 van Honthorst became a member of the Utrecht Guild of St Luke, for which he served as dean in 1625, 1626, 1628 and 1629. As early as 1621, even before he had become a member of the Guild, van Honthorst began to attract international attention. A painting of Aeneas Fleeing from the Sack of Troy (untraced) was described enthusiastically in a letter of 1621 from Dudley Carleton, British Ambassador to The Hague, to the Earl of Arundel, in London. Van Honthorst’s most important pictures of the early 1620s are his numerous artificially illuminated representations of both genre and religious subjects. Among the largest and most interesting of these is the full-length, life-size Christ Crowned with Thorns (c. 1622; Amsterdam, Rijksmus.). He also executed a number of paintings usually described as a Merry Company (e.g. 1622; Munich, Alte Pin.). Such compositions probably represent aspects of the parable of the Prodigal Son, rather than being pure genre depictions. The earliest example of this theme (1620; Florence, Uffizi; see fig.), the picture described by Mancini as a ‘cena di buffonarie’ (‘meal of buffoonery’), was executed in Italy for Cosimo II rather than in Utrecht. In such compositions van Honthorst, like his Utrecht compatriot Dirck van Baburen, was probably strongly influenced by Bartolomeo Manfredi’s interpretation of Caravaggio’s style. Van Honthorst also painted numerous genre scenes illuminated by artificial light, such as the Young Man Blowing on a Firebrand (c. 1622; Brussels, priv. col., see Judson, 1959, fig.), apparently a re-creation of a lost antique picture described by Pliny the elder, and the Dentist (1622; Dresden, Staatl. Kstsammlungen), a Caravaggesque version of the traditional Netherlandish theme, painted for George Villiers, Duke of Buckingham.

In contrast to van Honthorst’s various candlelight depictions are a number of musical subjects, all executed on either panel or canvas, which utilize the steep di sotto in sù perspective associated with Italian ceiling and wall frescoes. The most interesting and unusual of these paintings is the Musical Ceiling (1622; Malibu, CA, Getty Mus.), actually a fragment of what must have been a much larger ceiling decoration van Honthorst perhaps executed for one of the rooms in his own house. A piece of what was once an extremely tall, narrow canvas depicting Venus and Adonis (4.00×2.12 m, cut down in the early 20th century; Utrecht, Cent. Mus., where it is incorrectly attributed to Jan van Bijlert), with the same provenance as the Musical Ceiling, seems to indicate that as early as 1622 van Honthorst may have decorated an entire room in the Italian manner, thus anticipating the kind of large-scale painted decorative programme with which he was later to become involved for the various palaces of the House of Orange Nassau.

Although van Honthorst continued to paint Caravaggesque works, by 1624 a number of his pictures began to depart from the usual stylistic formulae of his fellow Utrecht Caravaggisti, and artificial illumination was used less frequently in his major compositions. In such single-figure compositions as the Merry Violinist (1623; Amsterdam, Rijksmus.) and its pendant, the Singing Flautist (Schwerin, Staatl. Mus.), the subject-matter and the composition owe their origins to various related paintings by the Utrecht artists Hendrick ter Brugghen and Dirck van Baburen. Van Honthorst added a strong sense of illusionistic space, however, by providing a window-like architectural framework. Neither painting uses the dramatic patterns of light and shade characteristic of van Honthorst’s earlier development.

During the mid-1620s van Honthorst’s style continued to fluctuate between his typically Caravaggesque, artificially illuminated compositions, such as the large and impressive Denial of St Peter (c. 1623), which reveals the influence of the French Caravaggesque artist Valentin de Boullogne, and such pictures as the Concert Group (1624; Paris, Louvre), with its steep illusionistic perspective, cool daylight effects and bright colours. This work may have been executed as an overmantel for the Dutch stadholder’s palace, Noordeinde, in The Hague, which would make it the first in a long series of commissions for the House of Orange Nassau. The diverse aspects of van Honthorst’s style are still clearly apparent in two of his more important works from 1625: The Procuress (Utrecht, Cent. Mus.), a typically Utrecht Caravaggesque composition on panel, with a candle as light source, contrasting physiognomic types, a Manfredi-inspired profil perdu and a compact, half-length compositional format; and the full-length canvas Granida and Daifilo (Utrecht, Cent. Mus.), based on the first Dutch pastoral play, Granida (1605) by Pieter Cornelisz. Hooft (1581–1647). This pastoral theme had been introduced into Dutch art only two years earlier by another of the Utrecht Caravaggisti, Dirck van Baburen. Van Honthorst’s picture seems also to have been painted for one of the stadholder’s palaces, indicating the growing courtly taste for pastoral and Classical themes in Dutch art at this time. Despite their differences in subject-matter and support, both pictures from 1625 reveal a crispness in the paint surface, and sharper outlines and edges than van Honthorst’s earlier works. This stylistic tendency was to dominate his later artistic production.

During the summer of 1627 Peter Paul Rubens spent several days in Utrecht and, according to Joachim von Sandrart who was then a pupil of van Honthorst, visited the studio of van Honthorst and also met other prominent Utrecht artists. The account is difficult to confirm: Rubens stayed at the Utrecht inn owned by ter Brugghen’s brother rather than at ‘De Poortgen’, suggesting that Sandrart, in relating the facts about this visit, was biased in favour of his master. During the same year van Honthorst was paid for two paintings for the royal hunting-lodge at Honselaarsdijk: Diana Hunting (1627; ex-Berlin, Grunewald, Jagdschloss, untraced since 1945, see Judson, 1959, fig.), and probably a recently discovered Diana Resting (New York, priv. col.). These pictures are the earliest works that firmly document van Honthorst’s association with the House of Orange Nassau, which was to play a significant part in the painter’s artistic development after the mid-1630s.

(iii) England, 1628.

From April until early December 1628 van Honthorst was in England. In addition to the large historiated portrait of King Charles I, his wife, Queen Henrietta Maria, and the Duke of Buckingham depicted as Mercury Presenting the Liberal Arts to Apollo and Diana, originally commissioned by Charles I for the Banqueting House in Whitehall, London (3.57×6.40 m; London, Hampton Court, Royal Col.), he also painted several portraits, including one of Charles I (London, N.P.G.), which may have served as the model for the Apollo in the Hampton Court picture. It is possible that van Honthorst’s earlier contacts with the Duke of Buckingham, who appears as Mercury in the Hampton Court painting, as well as with Rubens, who later painted the ceiling in the Banqueting House and had also worked for the Duke of Buckingham, were instrumental in his obtaining this important commission. The picture was extremely well received, to judge by Sandrart’s statement that van Honthorst was paid 3000 guilders and given many other costly gifts. On 28 November 1628 van Honthorst was made an English citizen and provided with a lifetime pension of £100 a year.

(iv) Utrecht, The Hague and international courtly circles, 1629–56.

Van Honthorst probably received another important commission from Charles I, which he executed only after his return to Utrecht: a large historiated portrait of Frederick V, King of Bohemia, and his Queen, Elizabeth Stuart, Daughter of James I, and their Children (1629; Marienburg, Prinz Ernst August von Hannover). The picture may be the one that is mentioned in an early inventory of St James’s Palace and is said to be based on Honoré d’Urfé’s pastoral work L’Astrée, one of the favourite poems of Frederick V of Bohemia (1596–1632). The success of the works painted for the English court were important factors in diverting van Honthorst’s talents in two new directions: towards an insipid but financially rewarding style of courtly portraiture and towards the more successful allegorical works in large-scale decorative schemes. With the death of Hendrick ter Brugghen in 1629 and van Honthorst’s abandonment of Caravaggism in the early 1630s, Caravaggesque history and genre painting in Utrecht began to lose much of its vitality.

During the first half of the 1630s van Honthorst’s international reputation continued to grow, especially in royal and courtly circles in England and elsewhere. In 1630, for example, his brother and assistant, Willem van Honthorst, was sent to England to deliver a group of paintings in person. When Kronborg Castle at Helsingør burnt down in 1629, Christian IV, King of Denmark and Norway, commissioned van Honthorst to paint various works including a series of four pictures based on the Aethiopica of Heliodorus of Emesa ( fl c. 220–50), and four illusionistic ceiling paintings depicting flying putti carrying royal monograms for the decorations of the redesigned and rebuilt castle, all eight of which were apparently completed by 11 October 1635 (in situ). There are numerous other works by van Honthorst commissioned for Kronborg, some of which are dated as late as 1643.

Van Honthorst was firmly established in the courtly circles of The Hague during the early 1630s, although he continued to reside in Utrecht until 1637. He was patronized by King Frederick V and painted numerous portraits for Prince Frederick Henry and his family. Between 1636 and 1639 van Honthorst was part of a team of artists involved with painting the decoration for the palaces of Honselaarsdijk and Rijswijk. He was paid the large sum of 6800 guilders for painting the ceiling decorations (untraced) for the grand hall at Rijswijk. It is likely that his work for the House of Orange Nassau was instrumental in his decision to move to The Hague, where he became a member of the Guild of St Luke in 1637. Among the best of the portraits painted at this time is the full-length double portrait of Prince Frederick Henry and Amalia van Solms (The Hague, Mauritshuis), executed shortly after van Honthorst took up residence in The Hague. In 1638, when Marie de’ Medici, Queen of France, made a state visit to the northern Netherlands, Frederick Henry had van Honthorst paint a portrait of her (Amsterdam, Hist. Mus.), which she presented to the burgomasters of Amsterdam during her visit to that city. Van Honthorst was elected dean of the guild in 1640.

In 1649 Constantijn Huygens, secretary to Prince Frederick Henry, and the architect and painter Jacob van Campen invited van Honthorst to help decorate the Oranjezaal of the Huis ten Bosch (see the Hague, §V, 3), the most important extant large-scale painted hall in the Netherlands. The iconographic programme celebrated the long-awaited peace that had been concluded at the Treaty of Münster in 1648, which at last brought about official recognition of the United Provinces. Prince Frederick Henry did not live to see this historic event, having died in 1647, but in the centre of the hall’s cupola, painted by van Honthorst and his workshop, he is glorified almost to the point of deification, as in Frederick Henry’s Steadfastness (in situ). His widow, Amalia van Solms, who oversaw the completion of the project, also appears prominently, dressed in mourning and holding a skull. Van Honthorst’s contributions to the Oranjezaal consisted only of allegorical portraiture, the best of which are the large Allegory on the Marriage of Frederick Henry and Amalia van Solms and the Allegory on the Marriage of William II and Maria Henrietta Stuart on the south wall (both in situ; see Judson, 1959, fig.).

In 1652 van Honthorst retired to Utrecht. There are relatively few works from after this date; almost all are portraits, the most interesting of which are the pendant portraits of the artist and his wife (1655; Amsterdam, Rijksmus.). The compositional and secondary elements suggest that these works celebrate the 35th anniversary of the marriage of van Honthorst and Sophia Coopmans.

2. Working methods and technique.

(i) Workshop and pupils.

Soon after van Honthorst joined the Utrecht Guild of St Luke in 1622 he established a large and flourishing workshop and art academy, which attracted numerous students. Joachim von Sandrart, who studied with van Honthorst from c. 1625 until 1628, recorded that there were approximately 25 students in the studio when he was there and that each one paid 100 guilders a year for tuition, a considerable sum for the period. In 1627 van Honthorst purchased a large house on the Domkerkhof (Cathedral cemetery), apparently to house his growing atelier. Among van Honthorst’s numerous pupils were Jan Gerritsz. van Bronchorst, Robert van Voerst (1597–c. 1636), Gerard van Kuijll (1604–73) and, according to Sandrart, the Dutch Italianate landscape painter Jan Both.

(ii) Drawings.

Unlike his fellow Utrecht Caravaggisti, van Honthorst left a relatively large number of drawings. Since a number of these can be related to paintings it is clear that especially after c. 1625 he followed the working methods of his teacher Abraham Bloemaert rather than those of Caravaggio, who eschewed drawing in favour of direct painting. One of the most interesting surviving sheets is a signed and dated copy (1616; Oslo, N.G.) of Caravaggio’s Martyrdom of St Peter in S Maria del Popolo, Rome. Among those drawings that can be directly related to paintings is the Prodigal Son (Vienna, Albertina) for the Merry Company (1622; Munich, Alte. Pin.). Most of the drawings, however, reveal similar preoccupations with Caravaggesque themes and artificial light effects, the contrasting areas of shadow being rendered in bold brown washes, as in Brothel Scene (c. 1623; Oxford, Ashmolean) and Old Woman Illuminating a Young Girl with a Candle (c. 1625; Leipzig, Mus. Bild. Kst.).

3. Character and reputation.

It is surprising, given van Honthorst’s early artistic and social success among the Roman aristocracy, to find him described by Mancini as ‘very reserved and melancholic’; but Mancini also praised him as ‘a man of his word’ who could be ‘trusted to deliver a painting on the date promised’. Van Honthorst was equally successful after his return to the northern Netherlands, especially in courtly circles. Constantijn Huygens, in his autobiographical notes (c. 1630), included the artist along with Abraham Bloemaert, Dirck van Baburen and Hendrick ter Brugghen as one of the most important Dutch history painters of the time. He was considered ‘one of the most famous painters of this [the 17th] century’ by Jean Puget de La Serre, a member of Marie de’ Medici’s French entourage, who was impressed by van Honthorst’s portrait of her (Amsterdam, Hist. Mus.). The same portrait was glorified in a poem by the Dutch writer Jan Vos. When van Honthorst’s brother Herman, a Catholic priest, was thrown into a Utrecht prison in 1641 for his religious activities, no less a person than Prince Frederick Henry intervened on his behalf, a clear indication of the stadholder’s high personal regard for the painter. He was a natural choice for the group of artists chosen by Huygens and van Campen in 1649 to decorate the Oranjezaal of the Huis ten Bosch. But a letter Huygens wrote the same year to Prince Frederick Henry’s widow, Amalia van Solms, makes it clear that van Honthorst’s reputation was by then beginning to slip, especially among the other artists working on the Huis ten Bosch decorations. Despite van Honthorst’s declining reputation towards the end of his career, he had already become extremely rich through his artistic endeavours. When he sold his house to the city of The Hague in 1645, he received the princely sum of 17,250 guilders. About the same time he lent Elizabeth, Princess of Hohenzollern (1597–1660), no less than 35,000 guilders. Various other contemporary sources attest to the fact that van Honthorst lived in The Hague like a grand seigneur rather than an artist or artisan.

Leonard J. Slatkes. "Honthorst, Gerrit van." In Grove Art Online. Oxford Art Online, http://www.oxfordartonline.com.proxy.lib.fsu.edu/subscriber/article/grove/art/T038821 (accessed May 8, 2012).

Person TypeIndividual