John Opie

British, 1761 - 1807

English painter. He was born in a tin-mining district, where his father was a mine carpenter. He had a natural talent for drawing and was taken up by an itinerant doctor, John Wolcot (the poet Peter Pindar, 1738–1819), who was an amateur artist and had a number of well-connected friends. Wolcot taught Opie the rudiments of drawing and painting, providing engravings for him to copy and gaining him access to country-house collections. Opie’s early portraits, such as Dolly Pentreath (1777; St Michael’s Mount, Cornwall, Lord St Levan priv. col.), are the work of a competent provincial painter and owe much to his study of engravings after portraits by Rembrandt. His attempts at chiaroscuro and impasto in Rembrandt’s manner gave his pictures a maturity that clearly startled contemporary audiences expecting to see works by an untutored artist. Thus in 1780, when a picture by him was exhibited in London at the Society of Artists with the description ‘a Boy’s Head, an Instance of Genius, not having ever seen a picture’, Opie was hailed as ‘the Cornish Wonder’. When he himself arrived in London, where he was promoted by Wolcot and his paintings were exhibited at the Royal Academy in 1781 and 1782, he was seen as a phenomenon, impressing even Joshua Reynolds, who is reputed to have remarked that Opie was ‘like Caravaggio and Velasquez in one’.

Opie’s initial success in London was short-lived, since for all his skills as a painter of rustic life he had yet to master the graces of society portraiture. He broke with Wolcot in 1783, but, armed with a natural shrewdness and an appetite for improving his abilities, he managed well, painting such portraits as the four canvases of the children of John Campbell, 5th Duke of Argyll (c. 1784; Inveraray Castle, Strathclyde) and Thomas Daniell and Captain Morcan, with Polperro Mine, St Agnes, in the Background (1786; Truro, Co. Mus. & A.G.), as well as subject pictures, including A School (exh. RA 1784; Lockinge House, Oxon), which displays a sympathetic feel for light and texture. In 1785 he executed his first history painting, and, although he painted portraits throughout his career (usually spot-lit images against a dark background), his most significant works are historical subjects, which are among the most original works of the period in England.

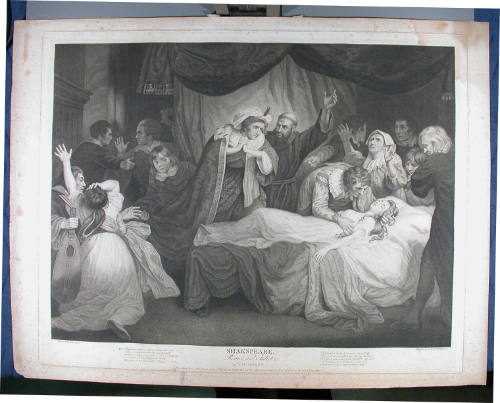

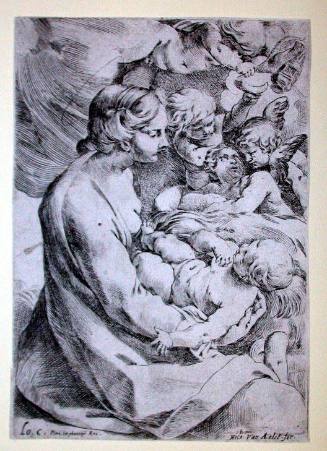

Nothing by ‘the Cornish Wonder’ could have prepared the public for Opie’s two history paintings exhibited at the Royal Academy in 1786 and 1787. In the dramatic James I of Scotland Assassinated by Graham at the Instigation of his Uncle the Duke of Atholl (1786; London, Guildhall, destr.) the figures of Graham and the semi-nude monarch were taken from Titian’s Death of St Peter Martyr (Venice, SS Giovanni e Paolo, destr.), and the draperies and expressions were treated with great vigour. Opie was elected ARA in 1786 and RA the following year, partly on the strength of this picture. In the summer of 1786 he travelled to the Netherlands; the acquaintance at first hand with the major works of Rubens and Rembrandt was crucial to his development as a history painter. The sequel to James I Assassinated was The Assassination of David Rizzio (1787; London, Guildhall A.G.), an even more dramatic picture. The two main figures, of Rizzio and his assassin (again drawn from Titian’s Death of St Peter Martyr), are flanked by two onrushing crowds. The theatrical light illuminating the richly textured fabrics and the alarmed expressions of the figures echoed by counter-poised outstretched arms owe as much to such works as Guido Reni’s Massacre of the Innocents (Bologna, Pin. N.) and Caravaggio’s Martyrdom of St Matthew (Rome, S Luigi dei Francesi) as to Titian. Both James I Assassinated and The Assassination of David Rizzio were probably commissioned by the print publisher John Boydell, and with Boydell’s Shakespeare Gallery, set up in 1786, Opie found a ready market for scenes from English history (e.g. Timon of Athens, 1790; Bolton, Mus. & A.G.). He also contributed paintings to Thomas Macklin’s Poets’ Gallery and Macklin’s Bible (e.g. St Paul Expelling the Evil Spirit from the Damsel of Philippi, c. 1795), as well as to Robert Bowyer’s edition of David Hume’s History of England (e.g. The Duke of York Resigned by the Queen, c. 1795; Stratford-on-Avon, Royal Shakespeare Mus.). All these works rely on chiaroscuro and dramatic gesture for their effect, and Opie handled his paint broadly, with a generous use of impasto. His admiration for the works of Reynolds led him to use bitumen in the backgrounds of his major pictures, which have deteriorated as a result.

By c. 1800 Opie was painting large-scale fancy pictures, such as The Angry Father, or The Discovery of the Clandestine Correspondence (exh. RA 1802; Birmingham, Mus. & A.G.), which were designed to cater for the taste established by Jean-Baptiste Greuze’s sentimental genre scenes. The appearance of these pictures may also be attributed to the influence of Opie’s second wife, the novelist Amelia Opie, as well as to a lack of portrait commissions during this period. In 1802 he visited the Musée Napoléon in Paris, and this contact with the Old Master paintings assembled in the Musée du Louvre from collections throughout Europe seems to have given even his fancy pictures a new nobility.

The success of Amelia Opie’s novels aided her husband’s career since, as James Northcote put it, she ‘drove all before her into his painting room’. By 1804 Opie was thriving. The number of his subject pictures dwindled so that in the last two years of his life he exhibited nothing but portraits, such as that of The Rev. Samuel Parr (exh. RA 1807; Holkham Hall, Norfolk). He lectured at the Royal Institution in 1804–5, and he was elected Professor of Painting at the Royal Academy in 1805. He lived long enough to deliver only four of the six lectures the Academy required of him. Although many of the ideas he presented were derived from lectures by Reynolds, Henry Fuseli and James Barry, Opie’s posthumously published Lectures on Painting (1809) are still valuable documents of late Georgian art theory.

Opie was a prominent figure in efforts to procure state support for British artists. Although he had been on strained terms with most of his colleagues, he was buried next to Reynolds in St Paul’s Cathedral. Praise for his work in such contemporary periodicals as The Artist was widespread and sincere, since he was among the most respected painters of his generation.

John Wilson. "Opie, John." In Grove Art Online. Oxford Art Online, http://www.oxfordartonline.com.proxy.lib.fsu.edu/subscriber/article/grove/art/T063630 (accessed May 1, 2012).

Person TypeIndividual