Image Not Available

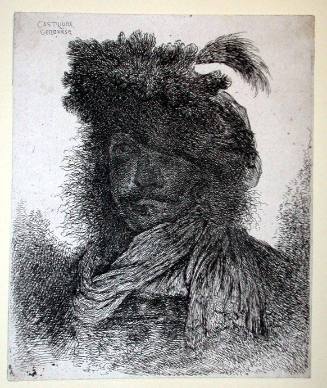

for Sir Godfrey Kneller

Sir Godfrey Kneller

British, 1646 - 1723

English painter and draughtsman of German birth. He was the leading portrait painter in England during the late 17th century and the early 18th, and, as such, the chief recorder of court society for almost 40 years. He popularized the kit-cat format for portraits and was also the founding governor in 1711 of the first proper academy of art in England. His older brother Johann [John] Zachary Kneller (b Lübeck, 1642; d London, 1702), with whom he was close, was also a painter; his works include watercolour miniatures and still-lifes, as well as copies of his more famous brother’s works.

1. Life and work.

(i) Early career, to 1688.

Kneller came from a distinguished family in Lübeck. His father was the city’s chief surveyor, and Kneller was first prepared for a career in the army, studying mathematics at the University of Leyden (now Leiden). However, it seems he had always been attracted to painting, and in 1662 he was sent to Amsterdam to pursue his studies, by one account under Rembrandt, by another under Ferdinand Bol. His earliest extant painting is an accomplished portrait of the Archbishop of Mainz, Johann Philipp von Schönborn (c. 1666; Vienna, Ksthist. Mus.), the style of which seems to be based partly on Anthony van Dyck and partly on Frans Luyckx, a Dutch artist much favoured at the Austrian court. Other extant early works include the Old Student, a vanitas piece painted as a pendant to his brother’s Young Student (both 1668; Lübeck, St Annen-Mus.), and Elijah and the Angel (‘The Angel Appearing to Tobit’, c. 1672; London, Tate), an awkward but ambitious subject picture indebted in composition to both Rembrandt and Bol. According to George Vertue, it was about this time that Kneller and his brother travelled to Italy where, Buckeridge claimed, he studied in Rome in the circles of Gianlorenzo Bernini and Carlo Maratti. Kneller also spent some time in Venice, where he is reputed to have made portraits for several noble families, although no works survive from this Italian period. About 1675 he returned to Lübeck for a year or so, afterwards moving to Hamburg and from there to London. Possibly he travelled to England in order to study further the works of van Dyck (M. Smith: The Art of Painting, London, 1692, pp. 24, 27), although the advice of some English merchants in Hamburg may have alerted him to the opportunities available for portrait painters in London. His brother must also have moved to England about the same time, since he is known to have been working in York in April 1677.

Kneller’s career prospered in England: he was charming, capable and, as Vertue noted, indefatigable; he was also industrious and abstemious, and at this time Peter Lely, the leading painter in London, could not take up all the available commissions. Kneller’s first portrait commissions came from John Banckes (1637–1710)—a merchant with business interests in Hamburg and with whom Kneller stayed on his arrival in London; of these only that of Banckes survives (1676; London, Tate). Soon afterwards he made a portrait of James Vernon (1677; London, N.P.G.), secretary to James Scott, 1st Duke of Monmouth, after which he was commissioned by Monmouth for portraits of himself (1678; Duke of Buccleuch priv. col.) and of his wife, Anne Scott, Duchess of Monmouth (untraced; engraved by Jan Vandervaart). Several portraits of the Scottish nobility followed, including John Hay, 1st Marquess of Tweeddale (1678; Floors Castle, Borders) and Anne, Duchess of Hamilton (1679; Lennoxlove, Lothian). In 1678 Kneller received a commission to paint a portrait of Charles II, which survives only in the form of an engraving (1679) by Robert White. This was made in conscious competition with an earlier portrait of the King by Lely, which had been commissioned by James, Duke of York, afterwards James II. Many thought Kneller’s the better work.

By 1682 Kneller was prospering sufficiently to move his studio to a large house in the piazza of Covent Garden, London; the following year both he and his brother became naturalized citizens. Since Lely had died in 1680, by this time Kneller was well established as the favourite court painter, one result of which was that he was sent to France by Charles II in 1684 to make a portrait of Louis XIV (untraced; copies at Drayton House, Northants, and Heckfield Place, Hants). With Charles’s death the following year and the accession of James, Kneller was at first forced to share his position with Willem Wissing, a Dutch artist, and with John Riley. But Kneller was by now at the height of his powers and, if challenged initially, soon rose effortlessly above them both, producing not only a fine portrait of James II (1688; Guyzance Hall, Northumb.) but also a large number of other grand and powerful full-length portraits. These include Louise de Kéroualle, Duchess of Portsmouth (Goodwood House, W. Sussex), Laurence Hyde, 1st Earl of Rochester (London, N.P.G.) and Philip, 4th Earl Wharton (Easton Neston, Northants), all painted in 1685. It was during this period that Kneller produced one of his favourite portraits, Michael Alphonsus Shen Fu-Tsung (‘The Chinese Convert’, 1685; London, Kensington Pal., Royal Col.), painted for James II. In this full-length portrait the sitter’s gaze is directed towards Heaven; one hand is on his heart, the other holds a crucifix. The handling of the paint, especially for the modelling of the head, is particularly delicate and fluid.

(ii) Later career, 1688–1723.

Following the accession in 1688 of William and Mary, Kneller and Riley were made joint Principal Painters to the Crown. After Riley’s death in 1691, Kneller held the office alone for the rest of his life. He was knighted in 1692, during a period when neither the King nor Queen sat ‘to any other person’ (Buckeridge). He also made one or two portraits of foreign monarchs, including Peter the Great (1698; London, Kensington Pal., Royal Col.). About this time Kneller also produced a group of larger and somewhat awkward allegorical works in celebration of the new sovereign: William III on Horseback (version, 1701; London, Hampton Court, Royal Col.) depicts the King as Protestant hero, surrounded by allusions to Astraea and the return of the Golden Age. The initial design is preserved in an oil sketch (1700; New York, priv. col., see Stewart, 1983, pl. 52), and another version (untraced) was formerly in the Hermitage, St Petersburg.

Kneller continued to maintain his fashionable social practice with as much energy as ever; Ozias Humphry recorded in his Memorandum Book (London, BL, Add. MS. 22950) an earlier report that in one day in 1693 the artist had no less than 14 sitters. This was the period of Kneller’s ‘Hampton Court Beauties’, suggested to Kneller by Lely’s earlier series of beautiful women, the ‘Windsor Beauties’ (London, Hampton Court, Royal Col.). Kneller’s include Isabella Bennet, Duchess of Grafton (1690; Euston Hall, Suffolk) and Margaret Cecil, Countess of Ranelagh (1690–91; London, Hampton Court, Royal Col.). These compare favourably with other portraits made in the 1690s, such as Annabella Dives, Lady Howard (1697; Easton Neston, Northants) and Sophia Osborne, Baroness Lempster (c. 1690–95; untraced, see Stewart, 1983, fig.). It was this private practice, aristocratic and lucrative, that was to serve Kneller well during the reigns of Anne (from 1702) and George I (from 1714); although neither monarch appears to have been especially interested in the arts, Anne jointly commissioned Kneller and Michael Dahl to paint a series of 14 portraits of admirals (c. 1702–8; London, N. Mar. Mus.). In 1697 Kneller made a visit to Brussels, where he was able to make a close study of works by Peter Paul Rubens. Hitherto his style had been a modified version of Baroque classicism, but as a result of this trip he lightened his palette and began to introduce more bravura into his work, as can be seen, for example, in the sketchier handling and more pastel tones of his head-and-shoulders portrait of the poet John Dryden (1697; Cambridge, Trinity Coll.).

Many of the works Kneller made at this time employ different formats to those used previously; most notable is that for the series of over 40 portraits of members of the Kit-Cat Club made between c. 1700 and c. 1720 (all acquired by the National Portrait Gallery, London, in 1945). This was a convivial Whig group, most of its members being writers or aristocratic politicians, although Kneller was also a member. The portraits were apparently gifts from the individual sitters to the publisher Jacob Tonson (1656–1736), the club’s secretary. The format selected by Kneller for this series, 914×711 mm (36×28 inches), became famously known in England as the kit-cat size, although a number of Dutch painters, Rembrandt notably, had used it in the first half of the 17th century. Its inspiration was undoubtedly Raphael, who used it for such portraits as Baldassare Castiglione (1515; Paris, Louvre). Larger than the head-and-shoulders size hitherto preferred in England (762×635 mm) and smaller than that usually employed for a three-quarter-length (1.27×1.02 m), Kneller’s kit-cat size allowed for half-length portraits to be made on the scale of life, and he almost always chose to include one or both of the sitter’s hands. The result is an unpretentious series of individualizing likenesses, sober and invariably free from decorative background detail. The members of this influential grouping of English Augustan society included Charles Fitzroy, 2nd Duke of Grafton (c. 1703), portrayed in an attitude of apparent indolence; John Vanbrugh (c. 1704)—whose first architectural commission came from another member of the club, Charles Howard, 3rd Earl of Carlisle—appropriately depicted by Kneller holding one of the instruments of his profession; and John, Baron Somers (c. 1715–16), with a new edition in his hand of Edmund Spenser’s romance epic, The Faerie Queene. The kit-cat series became very well known and was greatly admired; a number of the paintings were reproduced in mezzotint in 1735 by John Faber the younger. Tonson, whose own kit-cat was painted in 1717, kept them in his house (destr.) at Barn Elms near Putney, London, where his nephew subsequently built a special room for their display.

Kneller’s prices were high. By 1705 his fee for a bust portrait was 15 guineas, while a kit-cat cost 20 guineas; he charged 30 guineas and 40 guineas respectively for a three-quarter-length and a full-length portrait. His income from his investments was such that in 1709 he began building a grand country retreat for himself, Whitton House (now Kneller Hall; altered 1848), near Twickenham, London. He personally decorated its main stairwell (destr.), with assistance from Louis Laguerre. The collection of pictures at Whitton included works attributed to Rembrandt and van Dyck, as well as Rubens’s modello (now St Petersburg, Hermitage) for the central section of the ceiling decorations for Inigo Jones’s Banqueting House, London, prepared by the artist in the early 1630s. In 1711 Kneller was the driving force behind setting up the first school for art in England, the Academy in Great Queen Street (see London, §III, 4). Other founder-members included Vertue, Laguerre, James Thornhill and Giovanni Antonio Pellegrini, as well as the sculptor Francis Bird, but it was Kneller who was elected governor. Drawing was the preferred medium for teaching purposes, and the Academy was maintained by subscription. Among the youthful artists studying there during his tenure as governor were Marcellus Laroon the younger and Joseph Highmore. Internal quarrels led to Kneller’s resignation in 1716, but five years of institutional authority provided the opportunity for him to impress on others the soundness of his techniques (see §2 below).

In 1715 Kneller was granted a baronetcy by George I, an unprecedented honour in England for a painter, which further enhanced his reputation among contemporaries. Late commissions include those portraits made in the tradition of the ‘Beauties’, for example Elizabeth Rothwell, Baroness Middleton (1713; Birdsall House, N. Yorks) and Mary Finch, Marchioness of Rockingham (1720; Birmingham, Aston Hall). Full-length portraits of men made during the same period include James, 4th Duke of Hamilton and 1st Earl of Brandon (c. 1715; Edinburgh, N.P.G.) and John Campbell, 2nd Duke of Argyll (1717; Duke of Buccleuch priv. col.). Among Kneller’s very last works are two portraits of Alexander Pope, one a profile bust in a feigned oval (1721; The Hirsel, Borders), the other showing the poet in a thoughtful pose, with a volume of Homer under his elbow (1722; Stanton Harcourt Manor, Oxon). In their design and handling both pictures show that Kneller’s powers were undiminished.

2. Working methods and technique.

Kneller was obsessed with capturing the likeness of his sitters, as André Rouquet later noted in his Present State of the Arts in England (1755), and he is known to have worked extremely rapidly, using preparatory drawings as the basis for his finished oils. Around one hundred examples (some signed) of Kneller’s drawings are known, most of which are in chalk or pen-and-ink (examples in London, BM and V&A). A number are studies of hands, heads and various accessories, but there are also some sketches of preliminary poses, undertaken in the early stages of a portrait design, that add to the meagre knowledge of his working practices. His pen-and-ink sketch of Admiral John Graydon (Burlington, U. VT, Robert Hull Fleming Mus.), for example, is a rapidly executed draft of the pose and costume he then went on to use for the three-quarter-length portrait of Graydon (1702–3; London, N. Mar. Mus.), one of the admirals depicted in the series by Kneller and Dahl.

Since Kneller ran an efficient studio he was able to work on numerous commissions concurrently. His prodigious output overall—around 870 works are known—is often explained as the result of his having set up an unprecedentedly large and highly organized portrait factory, which he staffed with specialist assistants individually responsible for drapery, perukes and so forth. There is, however, no contemporary evidence to support this, and his studio is more likely to have accommodated a much looser grouping. It would have included those who were assistants at one time or another, such as Edward Byng (c. 1676–1753), Marcellus Laroon the elder (1653–1702), James Worsdale (c. 1692–1767) and John James [Johann Jakob] Backer (1648–97), also known (in Antwerp) as Nicolas de Backer; others were simply pupils who went on to set themselves up as independent artists. These include the Irish-born Charles Jervas who spent a year there, probably in 1694–5, and the young German Johann Leonhard Hirschmann (1672–1750), who studied in Kneller’s studio c. 1704 before returning to Nuremberg to practise as a portrait painter and printmaker.

3. Critical reception and posthumous reputation.

At his death Kneller left a large fortune, much of which was the result of having shrewdly invested his income from painting. He bequeathed all his drawings (of which six sketchbooks and an album of miscellaneous sheets are now in London, BM) and the many unfinished paintings in his studio to his long-term assistant and leading drapery painter, Edward Byng, a number of which Byng and others appear to have afterwards completed. At Kneller’s sale, organized in London by Christopher Cock for 18–20 April 1726, buyers included Sarah Churchill, Duchess of Marlborough, and Lionel Sackville, 1st Duke of Dorset, who subsequently arranged for one purchase he made, a portrait of Queen Caroline and her Children (Wrest Park House, Beds), to be finished by Jacopo Amigoni. The low esteem into which Kneller’s reputation fell in the course of the later 18th century is clearly in part due to the fact that many observers were unable to distinguish works in his own hand from those posthumously finished by others, from imitative portraits by lesser artists and from straightforward fakes. The fiction of Kneller cynically setting up a mass-production process in order to amass wealth soon established itself. The connoisseur and art historian Horace Walpole, 4th Earl of Orford, believed that where Kneller had ‘offered one portrait to fame, he sacrificed twenty to lucre’ (Anecdotes, ii, p. 202); the portrait painter James Northcote was later to describe the bulk of Kneller’s output as little more than ‘hasty slobbers’ (E. Fletcher, ed.: Conversations of James Northcote R.A. with James Ward, London, 1901, p. 211).

Despite his detractors, Kneller had many admirers in the early years after his death—William Hogarth, for example, owned an engraved set of kit-cats—and he continued to influence leading painters into the second half of the century. Joshua Reynolds, who owned a Kneller self-portrait (untraced) previously in the possession of Dr Richard Mead and who was once seen keenly admiring Kneller’s portrait of Nathaniel, 3rd Baron Crewe of Stene (1698; Oxford, Bodleian Lib.), was upbraided in 1753 by John Ellis (1701–57), a former Kneller pupil, for not painting ‘in the least degree in the manner of Kneller’ (J. Northcote: Supplement to the Memoirs of … Sir Joshua Reynolds, London, 1815, p. xvii). Yet Reynolds was later to copy closely the design used for Mary Sackville, Countess of Dorset (1690–91; London, Hampton Court, Royal Col.), one of Kneller’s ‘Hampton Court Beauties’, for his own full-length of Elizabeth Gunning, Duchess of Hamilton and Argyll (1760; Port Sunlight, Lady Lever A.G.). Another borrower was Joseph Wright of Derby. His portrait of Mrs Robert Gwillym (1766; St Louis, MO, A. Mus.), in which she is shown seated in a landscape, guitar in hand, almost exactly follows the format of Kneller’s lute-playing Arabella Hunt (c. 1692; UK Gov. A. Coll.), widely known through the mezzotint published in 1705 by John Smith (i). Even the Danish artist Vigilius Eriksen chose to base the horse that appears in his large equestrian portrait of Catherine the Great on Brilliante (1762; Moscow, Tret’yakov Gal.) on that invented by Kneller over 60 years earlier for his own William III on Horseback. Although Kneller’s posthumous influence dissolved soon after the mid-18th century, and his name unfairly became a synonym for shoddy ineptitude, studies by Collins Baker in the early 20th century and by Stewart in the 1970s and 1980s have done much to restore his reputation as a skilful and influential artist.

David Cast. "Kneller, Godfrey." In Grove Art Online. Oxford Art Online, http://www.oxfordartonline.com.proxy.lib.fsu.edu/subscriber/article/grove/art/T046946 (accessed May 1, 2012).

Person TypeIndividual

Italian, c. 1610 - 1665