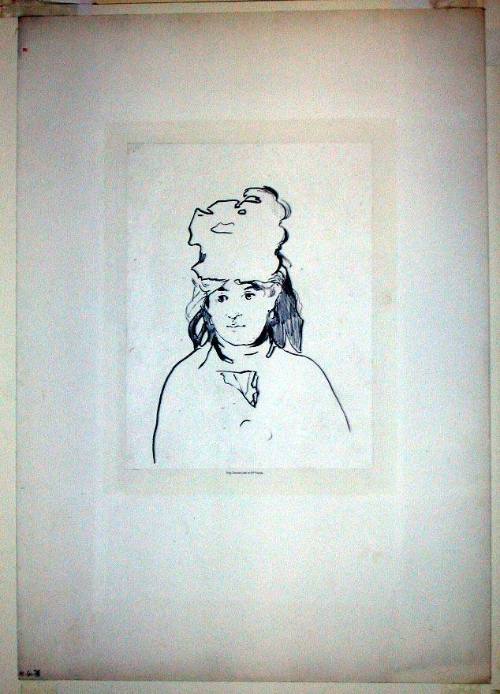

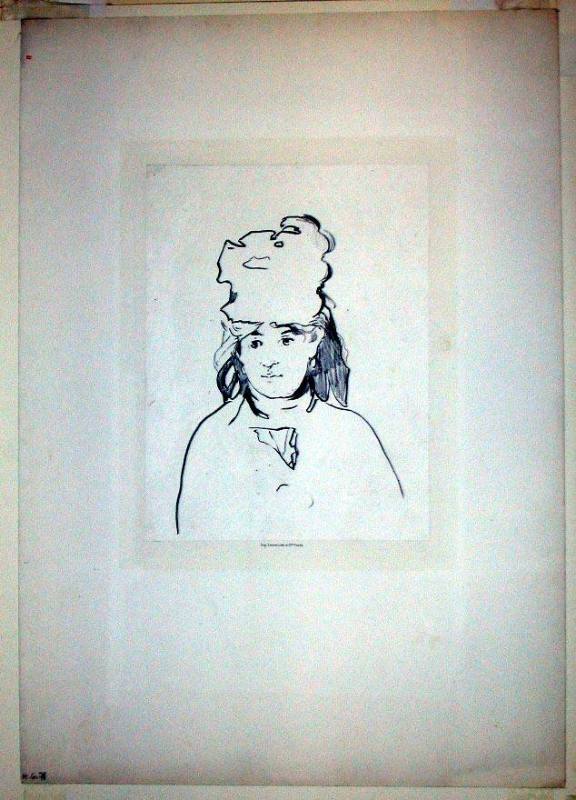

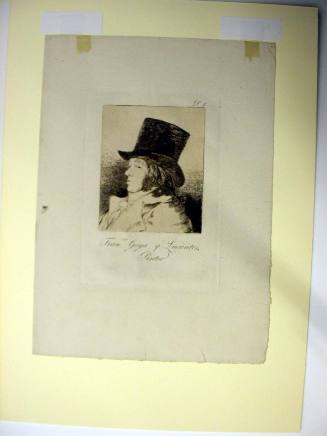

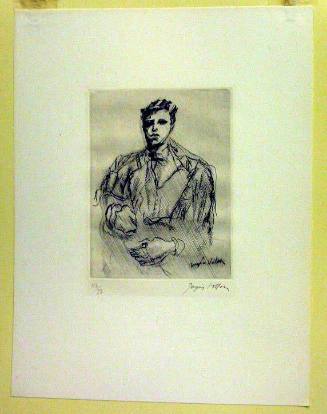

Edouard Manet

French, 1832 - 1883

French painter and printmaker, one of the giants of 19th-century art. He was the son of a senior civil servant in the Ministry of Justice and inherited considerable wealth when his father (who disapproved of his choice of career) died in 1862. His upper middle-class background was important, for although he was seen as an artistic rebel, he always sought traditional honours and success and he cut an impeccable figure as a man about town. He trained under Couture, 1850–6, but his own style was based mainly on a study of the Old Masters at the Louvre, and particularly Spanish painters such as Velázquez (his greatest artistic hero) and Ribera. During the 1850s he visited museums in the Netherlands, Germany, Austria, and Italy and it is one of the ironies of Manet's career that a painter with such reverence for the art of the past should be so much attacked for his modernity. His initial taste of official disfavour came when his first submission to the Salon—The Absinthe Drinker (1859, Ny Carlsberg Glyptotek, Copenhagen)—was rejected. He had two paintings accepted in 1861, but then in 1863 his Déjeuner sur l'herbe (Mus. d'Orsay, Paris) caused a scandal. It was turned down by the Salon and was shown instead at the Salon des Refusés, set up specially for such rejected paintings. Its hostile reception was based on moral as well as aesthetic grounds, for nudity was considered acceptable only if it was sufficiently remote in time or place and this showed a naked woman having a picnic with two contemporary, clothed men. Manet caused even greater outrage two years later when his Olympia (1863, Mus. d'Orsay) was exhibited at the Salon. The reclining nude figure was based on Titian's Venus of Urbino (which Manet had copied in Florence ten years earlier), but her blatant sexuality was thought an affront to accepted standards of decorum, and one critic wrote: ‘Art sunk so low does not even deserve reproach.’ Manet was denounced also for his bold technique, in which he eliminated the fine tonal gradations of academic practice and created vivid contrasts of light and shade: ‘The shadows are indicated by more or less large smears of blacking’, wrote another critic; ‘The least beautiful woman has bones, muscles, skin, and some sort of colour. Here there is nothing…but the desire to attract attention.’ From this time, Manet reluctantly found himself acquiring a reputation as a leader of the avant-garde, becoming a respected member of the group of young Impressionists who met at the Café Guerbois and elsewhere. But despite their admiration for him, Manet stood somewhat aloof from the group (although he enjoyed going to the races with Degas, who was also from the upper middle class) and did not participate in the Impressionist exhibitions. He did, however, adopt the Impressionist technique of painting out of doors (encouraged by Berthe Morisot, who became his sister-in-law in 1874), and his work became freer and lighter in the 1870s under their influence. In the late 1870s Manet became ill with a disease diagnosed as locomotor ataxia (brought on by syphilis), which caused him bouts of great pain and extreme tiredness. Increasingly he preferred to work in pastels, which were less physically demanding than oils, but his last great painting, A Bar at the Folies-Bergère (1882, Courtauld Gal., London), is unsurpassed in 19th-century art for sheer beauty of technique. He died in agony a week after having a gangrenous leg amputated. The official honours he had craved—in the form of a second-class medal at the Salon and membership of the Legion of Honour—came too late (1881) to be enjoyed.

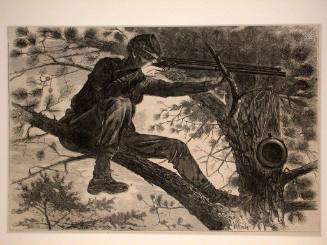

Manet was a complex and many-sided artist. He painted a great variety of subjects (he was also a skilled etcher and lithographer) and rarely repeated himself. His approach was completely undogmatic and he was reluctant to theorize: his friend Émile Zola wrote of him, ‘In beginning a picture, he could never say how it would come out.’ His work often has a feeling of complete freshness and spontaneity, yet he would often repaint and rework pictures or even cut them into fragments. His greatest strength was with modern-life subjects (he sketched constantly in the boulevards and cafés of Paris), but although he is accused by some critics of having no imagination, of being able to paint something only if he had it in front of him, his pictures are far from being straight transcriptions of nature. They are, indeed, sometimes enigmatic and elusive, as with A Bar at the Folies-Bergère, and seem to be more concerned with the act of painting than with the ostensible subject. It is partly in this freedom from the traditional literary, anecdotal, or moralistic associations of painting that he is seen as one of the founders of ‘modern’ art, and it is significant that the official title of the first Post-Impressionist Exhibition, organized by Roger Fry in 1910, was ‘Manet and the Post-Impressionists’.

"Manet, Édouard" The Oxford Dictionary of Art and Artists. Ed Ian Chilvers. 9Oxford Reference Online. Oxford University Press. 6 March 2012

Person TypeIndividual

French, 1824 - 1898

French, 1864 - 1901