Wang Hui

Chinese, 1632 - 1717

Chinese painter. He was one of the group of painters of the early Qing period (1644–1911) known as the Four Wangs; the others were Wang Shimin, Wang Jian and Wang Yuanqi (see Orthodox school). Wang Hui came from a family of painters, and his own career began in 1651, when he was discovered by Wang Jian and became the pupil of the latter and of Wang Shimin.

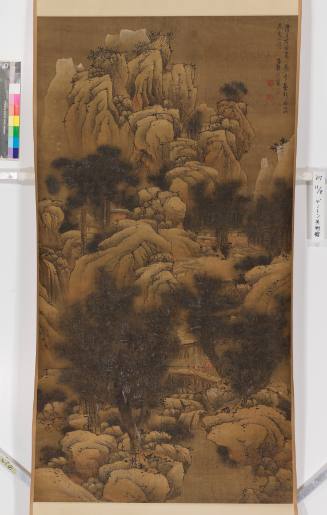

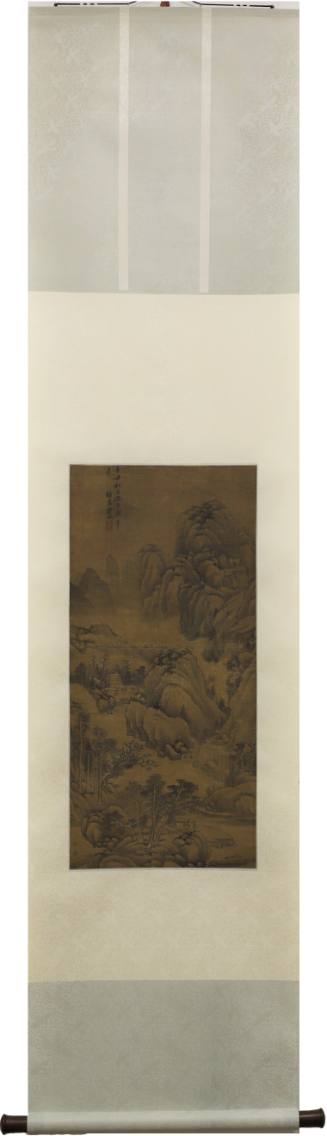

Wang Hui: Mountains in Autumn, hanging scroll, ink and colours…Wang jian and Wang Shimin (see Wang (ii), (1)) taught landscape painting according to the methods advocated by Dong qichang, who in his theory of a Southern school had attempted to reconstruct the whole history of literati painting. Dong emphasized Yuan-period (1279–1368) recluse painters such as Wu Zhen and Huang Gongwang, who brought landscape painting to a pre-eminent position among the subjects preferred by the literati. Through nature, as experienced by the landscape artist, ideas on the workings of the universe were expressed, in a manner, moreover, that distinctively revealed the character of the individual (see fig.).

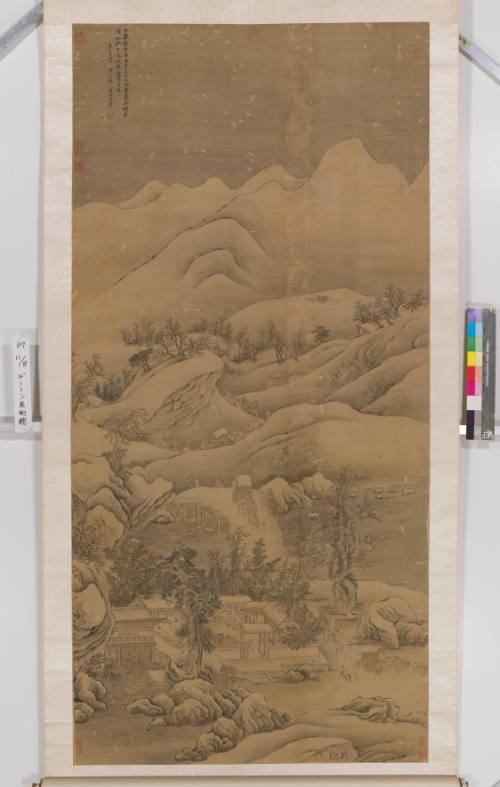

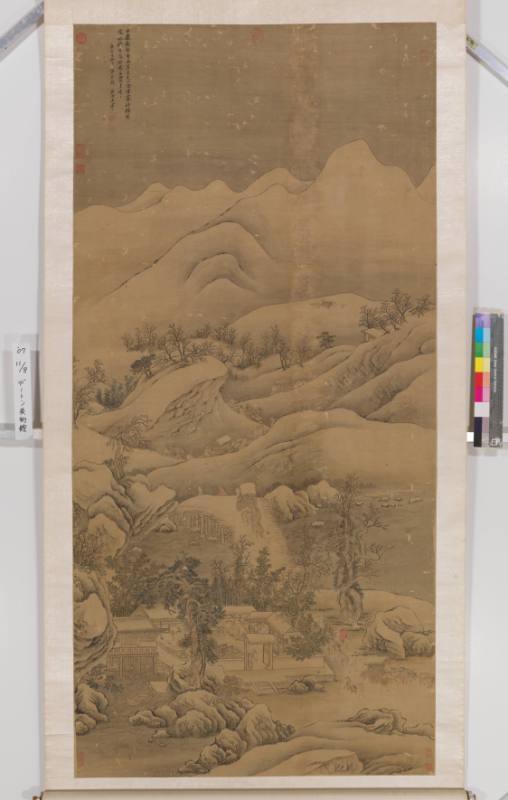

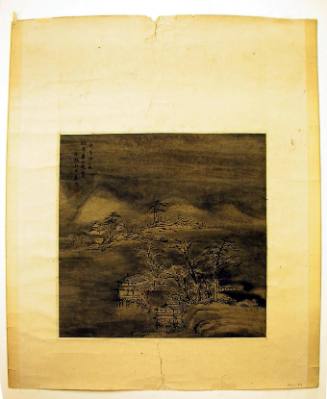

Wang Hui: Landscapes after Ancient Masters, leaf G, Peach Blossom…Under the guidance of Wang Shimin and Wang Jian, Wang Hui sought to paint works that were ‘transformations’ of classical styles. However, whereas his masters had principally followed the brush style of the great late-Yuan masters Huang gongwang and Wang meng, Wang Hui developed his own transformations of the styles of virtually all the principal Song (960–1279) and Yuan masters. His creation of a ‘Grand Synthesis’ (da cheng) of Song and Yuan landscape styles was made possible by his study of the many ancient masterpieces in Wang Shimin’s personal collection and his creation of a particular brush idiom for each style. Wang Shimin himself had reproduced a number of such paintings from his own collection, on a reduced scale, in the albums Xiaozhong xianda (‘The great revealed through the small’; Taipei, N. Pal. Mus., and Shanghai Mus.), and Wang Jian imitated him. In such works, repetition of strokes not only reproduces the appearance of the older style, whether in ink monochrome or colour, on paper or silk, but also reveals the forces immanent in the landscape, which previously were hidden and grasped only through an indefinable sense of ‘life-motion’. The meaning of such concepts as ‘dragon-veins’ (longmo) is conveyed with startling clarity by these repeated brushstrokes. Certain elements in paintings are repeated, including particular kinds of trees, rocks or other natural or manmade elements of landscape. Appropriate patterns of texture strokes (cun) were used to distinguish one style from another. A single artist such as Wang Hui would display a variety of Song and Yuan landscape styles within the compass of a series of ten or twelve album leaves, contained within an accordion mounting, and usually concluding with a winter scene. Generally, the stylistic origin of each leaf or scene is briefly indicated in the artist’s inscription; such albums must have served a useful purpose as a succinct overview of the history of Chinese painting. For some of these album series, Wang Hui cooperated with his exact contemporary Yun shouping, creating a brilliant alternation of landscape and floral subjects, as in the album Flowers and Landscapes (1672; Taipei, N. Pal. Mus.).

Wang Hui worked for almost 30 years under the direction of the two elder Wangs, reaching his prime during the 1670s and 1680s. Paintings such as the handscroll Taihang shanse (‘Colours of Mt Taihang’; 1669; Princeton U., NJ, A. Mus.), with a title added by Wang Shimin, typify his achievement. He was so successful in following the classic landscape styles that some of his works were passed off as original Song or Yuan paintings; his Travellers (Taipei, N. Pal. Mus.), for example, was long attributed to Fan Kuan. The critical apparatus of connoisseurship originated only with the theories of Dong Qichang, and thus Wang Hui’s paintings, in which concepts such as ‘dragon-veins’ and ‘breath-force’ were made visible, corresponded point for point with contemporary understanding of ancient paintings.

The deaths of Wang Jian (1677), Wang Shimin (1680) and Yun Shouping (1690) must have deprived Wang Hui of his accustomed encouragement and example. Resident in Beijing, he continued to paint prolifically for the court, but in a manner less varied than that of his earlier works. His paintings from this period reflect a preference for a manner derived from the Yuan master Wang Meng, although some titles, such as Landscape after Yan Wengui and Juran (long handscroll, 1713; Princeton U., NJ, A. Mus.), acknowledge a debt to earlier painters.

Under the Kangxi emperor (reg 1662–1722) Wang Hui directed the team that created the great series of outsize handscroll paintings, the Nanxun tu (‘Paintings of southern progress’; Beijing, Hist. Mus. and New York, Met.), recording imperial tours of inspection in the south, for which his long experience of organizing complex compositions with myriad details must have stood him in good stead. However, it is impossible to identify Wang’s individual contribution to such collaborative works.

Roderick Whitfield. "Wang Hui." In Grove Art Online. Oxford Art Online, http://www.oxfordartonline.com.proxy.lib.fsu.edu/subscriber/article/grove/art/T090615 (accessed May 8, 2012).

Person TypeIndividual