Kuncan

Chinese, 1612 - 1673

Chinese painter and Buddhist monk. He is known as one of the ‘Four Great Monk Painters’ of the early Qing dynasty (1644–1911), along with Shitao or Daoji, Zhu Da and Hongren, and as one of the greatest ‘Individualist’ painters of the 17th century (a group of artists that is always counterposed with the so-called ‘Orthodox’ painters of the 17th century).

As a youth he studied the classics and prepared himself for the civil service examinations, at the same time becoming interested in painting and Buddhism. Inspired by a Confucian scholar in his home town who was also a Chan (Jap. Zen) Buddhist, Kuncan decided to dedicate his life to Chan Buddhism; in 1638, to show his determination, he shaved off his hair. Encouraged by his mentor, he travelled to the Jiangnan region, the area south of the Yangzi River, to seek further instruction in Buddhism. While in Nanjing, Kuncan was introduced to the teachings of the famous patriarch Zhuhong (1535–1615), who was noted for his enthusiasm for synthesizing the three doctrines of Buddhism, Confucianism and Daoism. Zhuhong’s philosophy became the guiding light for his life. When he returned to Hunan Province, Kuncan settled in Taoyuan County and, under further instruction from his mentor, attained a kind of spiritual enlightenment.

During the turmoil caused by the invasion of the Manchu army and the establishment of the Qing dynasty (1644–1911) in 1644–5, Kuncan wandered deep into the countryside of the Taoyuan area, a region associated with the mythical Taohua yuan (Peach Blossom Spring), as described in the allegorical prose work written by Tao Yuanming in the 4th century AD. He stayed in the wilderness for three months, suffering considerable hardship. In 1654 he took up residence in the Dabaoen Temple in Nanjing where, under another noted monk, Juelang (1592–1659), he supervised the editing of a new edition of the Dazang jing, the Chinese Buddhist canon. He soon became acquainted with such distinguished scholars as Qian Qianyi (1582–1664) and Gu Yanwu (1613–82) and painters such as Cheng Zhengkui. The earliest extant paintings by Kuncan date from this period.

In 1659, after becoming an official disciple of Juelang, he moved to the Youqi Temple on Mt Zutang, not far from Nanjing, where he lived, except for a few trips, for the rest of his life. An early journey was to the famous Mt Huang range in southern Anhui Province (c. 65 km north-west of She xian), known for its great scenic beauty and a subject of many contemporary paintings (see Anhui school). He remained there for more than a year, during which time he did many paintings of the local topography. Most of his dated works that survive are from the period 1660–63, the most productive of his artistic career.

An extreme introvert who suffered from poor health, Kuncan had an idiosyncratic personality and seldom socialized with his contemporaries (some of whom were members of the Nanjing school). One exception was Cheng Zhengkui, who became his closest friend. They often visited each other and painted together, sometimes even collaborating on paintings. Cheng often invited Kuncan to view his collection of paintings and calligraphy and to discuss them together. Cheng had been strongly influenced by the theories and style of Dong Qichang, the connoisseur, painter, calligrapher and theorist who founded the Orthodox school of painting in the late Ming period (1368–1644), and doubtless brought some of Dong’s ideas to Kuncan.

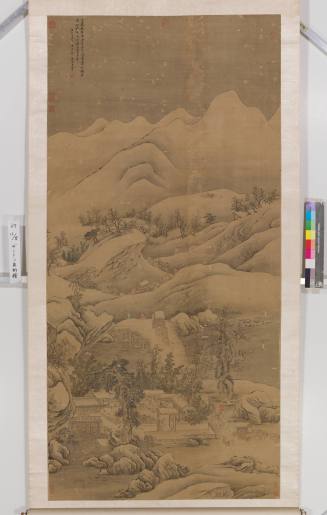

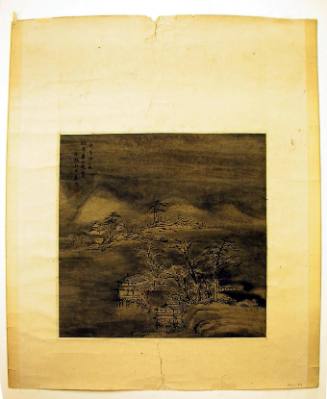

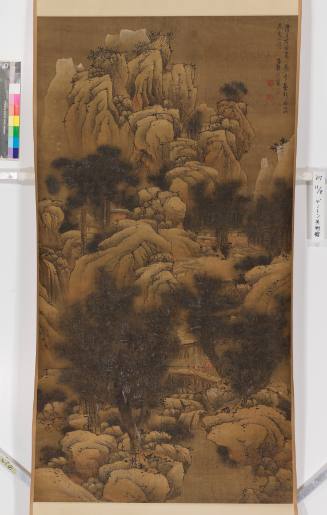

Kuncan’s painting style was inspired by such old masters as Juran, Huang Gongwang and Wang Meng. He was deeply interested in Wang Meng and developed his own style from Wang’s works. Critics have commented that Kuncan’s paintings, like Wang Meng’s, are full of life, vigorous, elaborate and colourful. His highly distinctive brushwork involved a dry-brush, crumbly brushstroke, quickly laid down in short staccato strokes that are interwoven into a dense, highly textured surface. Among the considerable number of his extant works are some that reflect his interest in depicting scenes he visited during his travels. Tiandu Peak (hanging scroll, paper, 1661; Beijing, Pal. Mus.) was one of many works inspired by his stay at Mt Huang. It shows the influence of 10th-century masters in its compositional use of a broad, open view. Another painting of the Mt Huang area, Thirty-six Peaks (hanging scroll, paper, 1663; Kansas City, MO, Nelson–Atkins Mus. A.), is a close-up view with the tightly knit composition that was also characteristic of Wang Meng. One of his best-known works is Baoen Temple (hanging scroll, paper, 1664; Kyoto, K. Sumitomo priv. col.), which depicts the temple in Nanjing where he spent almost ten years. An Album of Four Leaves Painted for Mr Qingzi [Cheng Zhengkui], painted from memory and based on scenes of Mt Huang, is one of his masterpieces. Of the four leaves in this album, two are in the British Museum, London, one in the Museum für Ostasiatische Kunst, Berlin (see fig.), and another at the Cleveland Museum of Art, OH. The compositions are all highly original, with dramatic movements and striking contrasts. They display the nervous energy evident in Wang Meng’s paintings but show a new sense of vision that is far from imitative.

Kuncan: Summer, album leaf from Album of Four Leaves Painted for Mr Qingxi [Cheng Zhengkui], ink and colours on paper, 314×643 mm, 1666 (Berlin, Museum für Asiatische Kunst); photo credit: Bildarchiv Preussischer Kulturbesitz/Art Resource, NY

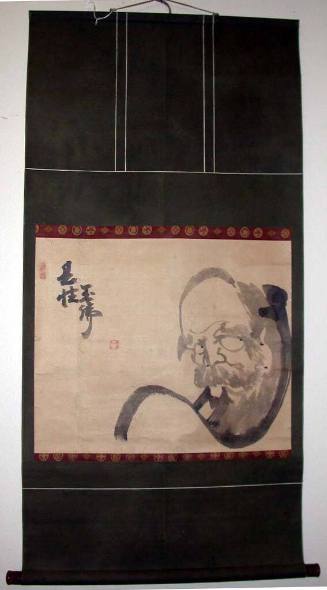

Kuncan also produced a number of figure paintings, mostly of Buddhist figures and monks, sometimes portraying himself as a Buddhist eccentric or a reincarnated saint. One of the most revealing paintings of this type was Monk Meditating in a Tree (untraced), in which he expressed his autobiographical views and experiences. In a long inscription typical of most of his works he wrote the following poem: ‘The question is how to find peace in a world of suffering. You ask why I came hither; I cannot tell the reason. I am living high up in a tree and looking down. Here I can rest free from all trouble like a bird in its nest. People call me a dangerous man, but I answer: “You are like devils”.’ (Translation Sirén, p. 147.)

Joseph Tsenti Chang and Chu-Tsing Li. "Kuncan." In Grove Art Online. Oxford Art Online, http://www.oxfordartonline.com.proxy.lib.fsu.edu/subscriber/article/grove/art/T048264 (accessed May 8, 2012).

Person TypeIndividual

Chinese, 1558 - 1639