Image Not Available

for Wen Zhengming

Wen Zhengming

Chinese, 1470 - 1559

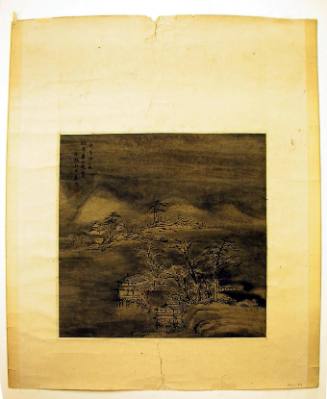

Wen Zhengming: Garden of the Inept Administrator, leaf B, album… Painter and calligrapher (see fig.). He was considered one of the Four Masters of the Ming period (1368–1644), along with Shen Zhou, Tang Yin and Qiu Ying. The most famous member of the second generation of Wu school artists, he profoundly influenced later painters. He was remarkable for his individuality as well as for the variety and range of his creativity. Although he was a thorough and diligent student, Wen Zhengming repeatedly failed the national examinations, the third level of civil service examinations. Finally, a local governor recommended him to a post in Beijing, where he lived from 1523 to 1527, working in the Hanlin Academy (see China, §V, 4(i)(d)) on the history of the Zhengde period (1506–21). Disillusioned by life in politics, he returned to Suzhou to become the focus of its artistic community.

Wen was deeply immersed in the study of the past. In common with his teacher, Shen Zhou, he drew on the works of the Yuan period (1279–1368) scholar-painters for inspiration, including the Four Masters of the Yuan: Huang gongwang, Wu zhen, Ni zan and Wang meng. The Yuan master Zhao Mengfu (see Zhao, (1)) exercised the most pervasive influence on Wen, and he also studied earlier styles of the Tang (AD 618–906) and Song (960–1279) periods. The wealth of material available in Suzhou collections made all this feasible. Once he was totally familiar with these earlier styles, Wen reworked them to incorporate his own distinctive style, frequently expressing his awareness of history through inscriptions on his paintings. He specialized in garden scenes, which were often depictions of particular places in Suzhou; trees, especially pine, cypress and juniper (see fig.); mountainscapes with an emphasis on rocks; commemorations of scholarly events such as journeys or departures; and illustrations of literature. He typically worked with refined, precise brushstrokes combined to form a complex surface pattern. As a literati painter (see China, §V, 4(ii)), he sought to express his own personality in his work, and his highly controlled intellect is always apparent behind the painting.

In Summer Retreat in the Eastern Grove (handscroll, ink on paper, c. 1512; New York, Met.), Wen combined the three traditional arts of a scholar: poetry, calligraphy and painting. At the end of the painting he wrote one poem in running script (xingshu) in the style of Huang tingjian, a second poem in cursive script (caoshu) in the style of Huaisu as transmitted by Huang Tingjian, and a third poem in running script in the style of Su shi. His selection reveals his good taste and skill in the styles of these earlier masters. The cool, precise painting is in the mode of Ni Zan. The composition is orderly and clear; the forms do not touch the lower edge of the scroll and are thus set back from the viewer. Clusters of rocks are placed along a subtle diagonal, leading the viewer from the lower right to upper left, and are topped by a few sparsely foliated trees. These motifs, along with the empty pavilion, are reminiscent of Ni Zan’s work. The austerity of the composition is reiterated by the economy of brushwork: there is nothing superfluous. Wen succeeded in capturing a fresh, cool garden scene through his keen comprehension of artistic antecedents.

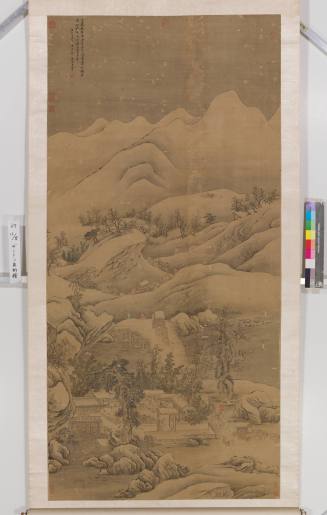

Master’s Liu’s Garden (hanging scroll, ink and colour on paper, 1543; New York, Met.) exemplifies a later treatment of the garden theme. This extraordinarily finely painted image was done for a friend, Liu Lin (1474–1561), who had just retired from government service. Wen painted a garden retreat based on ones already existing in Suzhou in anticipation of what his friend would probably construct. Two crossed willows invite the viewer across the water to enter the thatched gate and then back through the V-shaped arrangement of trees towards the lofty pavilion, where a scholar entertains a visitor. At the upper left Wen brushed a poem and dedication in standard script (kaishu), referring to the delightful view and peaceful atmosphere. The brushwork is soft and lyrical, with delicate pastel colouring: warm brown washes describe earth forms and tree trunks; pale blue and ink dots define the foliage.

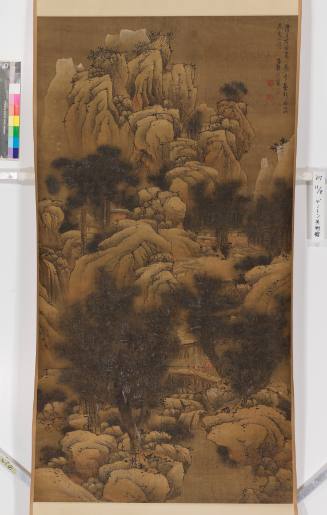

By contrast, in A Thousand Cliffs Vying in Splendour there is a palpable sense of movement created by tilting, twisting forms. Within the constricted limits of the scroll, Wen piled rock on rock to build up a richly patterned mountainscape inspired by considerations of formal design rather than verisimilitude. The composition is densely packed, and the drawing is firm and incisive rather than soft and feathery. In the foreground two scholars sit enjoying the nearby pool and waterfall. Several trees connect this with the overwhelming mountain in the background; there is no view into the distance to offer relief. The mountain itself is constructed of rock masses topped by small pines in the mode of Huang Gongwang. The tightly controlled composition and strong brushwork make this commanding work one of Wen’s masterpieces.

Wen made repeated use of the motifs of pine, cypress and juniper, which have particular connotations of the perpetual struggle of the human will (see fig.). In Old Cypress and Rock (Gubo tu; handscroll, ink on paper, c. 1550; Kansas City, MO, Nelson–Atkins Mus. A.) Wen exploited the complex design of the cypress in its echoing of the shape of the rock. The range of ink tones from soft, wet grey to dense, dry black is astonishing; the virtuoso brushwork, based on calligraphic technique, alludes to Zhao Mengfu. As in A Thousand Cliffs Vying for Splendour, there is little three-dimensional space: Wen emphasized the flat, decorative pattern of the forms. The painting and its ten accompanying poems express wishes for a quick recovery from illness of the poet, playwright and calligrapher Zhang Fengy (1527–1613). The cypress symbolizes perseverance, the promise of youth and the healing powers inherent in the plant.

Typical of classical scholars of the 16th century, Wen was a prolific poet. Much of his output reflects the formal grace of poetry masters of the Tang and Song dynasties, and it is rich in the visual imagery of landscapes and the changing seasons. Renowned also as a connoisseur, Wen was frequently called on to authenticate new additions to Suzhou collections, and he conducted careful research into the history of painting. Although his writing was refined and meticulous, it never attained the same stature as his painting and calligraphy. His collected writings were published in 1543 in Futian ji (‘Extensive fields collection’).

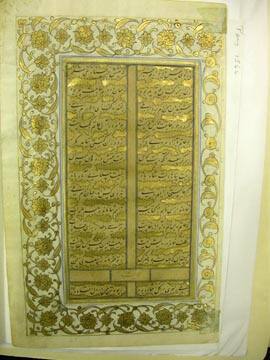

As a youth Wen Zhengming was a poor calligrapher, but he practised diligently and eventually he and his life-long friend Zhu Yunming were recognized as the two greatest calligraphers of the Ming period. Not only did Wen write in the modern script types of regular (kaishu), running (xingshu) and cursive (caoshu), but as part of his exploration of the past he also wrote in the archaic seal (zhuanshu) and clerical (lishu) scripts. During his years as an official in Beijing, Wen brushed poems on a suitably impressive imperial scale. In Waiting upon the Emperor’s Return from the Southern Suburbs (Gonghou dajia huan zi nanjiao; hanging scroll, ink on paper; New York, Met.) Wen used formal imagery and large, blocky standard script characters to please the emperor. The style is derived from the great Song-period calligrapher Huang Tingjian, with the emphatic use of the diagonal ‘oar stroke’. During his own lifetime Wen was best known for his small regular script (xiao kaishu) based on that of Wang Xizhi (see Wang (i), (1)); Lu Ji’s The Art of Letters (Lu Ji Wenfu; handscroll, ink on paper, 1544–7; New York, Met.) offers a neat and precise example of this. It is marked by a stable, systematic composition and well-balanced proportions. The full-bodied characters are accentuated by sharp points, and the thinning and thickening strokes impart a lithe rhythm.

Wen’s free and spontaneous running script is represented in a series of letters to his family (1523; Lyme, NH, Mr and Mrs Wan-go H. C. Weng priv. col.) and a letter to Hua Yun (1549; New York, Met). Both are imbued with informal natural rhythms and written with an exposed brush tip (lufeng; see China, §IV, 1). Wen had two styles of cursive script: one was lean and firm, based on Wang Xizhi, to which Wen contributed angularity and tapering finishing strokes; the other, freer style combined elements from Huaisu and Huang Tingjian. The Huangting jing (handscroll, ink on paper, 1558; Lyme, NH, Mr and Mrs Wan-go H. C. Weng priv. col.), a Daoist scripture that discusses the nourishment of the human body, is a rare example of Wen’s seal script, in which he re-created the style of the late 8th-century AD calligrapher Li Yangbing.

Alice R. M. Hyland. "Wen." In Grove Art Online. Oxford Art Online, http://www.oxfordartonline.com.proxy.lib.fsu.edu/subscriber/article/grove/art/T091122pg1 (accessed May 8, 2012).

Person TypeIndividual

Chinese, 1558 - 1639