Wang Jian

Chinese, 1598 - 1677

Chinese painter. He was one of the group of painters of the early Qing period (1644–91) known as the Four Wangs; the others were Wang Shimin, Wang Hui and Wang Yuanqi. The Four Wangs are credited with establishing the principles of the Orthodox school as inspired by Dong Qichang. Wang Shimin was Wang Jian’s friend and, being six years senior, his mentor. Both artists came from prominent families in Taicang but were unrelated. Wang Jian was the great-grandson of the famous collector Wang Shizhen and inherited his collection of paintings. Owing to his distinguished ancestry, under the Chongzhen emperor (reg 1628–44), Wang Jian was appointed to the government post of Prefect of Lianzhou in Guangdong Province, from which his hao, ‘Lianzhou’, derives. He served only briefly, however, and lived the rest of his life in retirement.

Wang Jian’s writings, largely in the form of inscriptions on paintings by his colleagues and protégés, such as Wang Hui, are frequently concerned with Dong Qichang’s theory of the Southern school, asserting the legitimacy of the Orthodox lineage and castigating contemporaries for their decadent artistic practices. The most serious charge levelled at ‘degenerate’ painters, by both Wang Jian and Wang Shimin, is that they failed to follow the old masters who form the basis for Southern school theory, particularly the Four Masters of the Yuan (1279–1368), Huang Gongwang, Wu Zhen, Ni Zan and Wang Meng. Not surprisingly, landscape albums in the styles of the old masters comprise a large part of Wang Jian’s output. At his most impressive, in his early and middle periods, he was capable of a higher level of technical skill and a greater textural richness than Wang Shimin (see Wang (ii), (1)), but in his late period he resorted to a similar formulaic monotony. Wang Jian was one of the most ‘painterly’ of the early Qing masters, combining a restrained use of colour with sensitive brushwork to create landscape scenes that go beyond simple imitation of his chosen models.

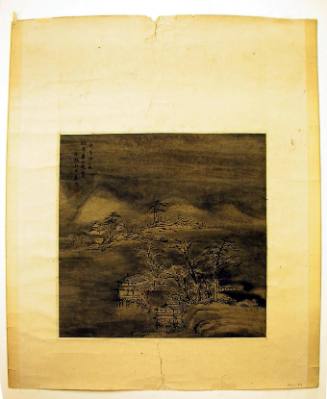

Wang Jian’s earliest surviving works date to the late 1640s; thereafter, he was prolific. The ten-leaf Album of Landscapes in Old Styles (1648; Berkeley, U. CA, A. Mus.) exemplifies his originality in reworking established motifs. The first leaf is inscribed ‘in the manner of Huichong’ in reference to the 11th-century monk–painter and in composition is typical of the Northern Song (960–1127) painter Zhao Lingrang; by the later part of the Ming (1368–1644) and early Qing, the styles of these two painters had been conflated. The leaf features the standard thatched hut and mist-enshrouded willows, but Wang introduces a human touch by depicting a departing guest looking back as an expression of affection for his host.

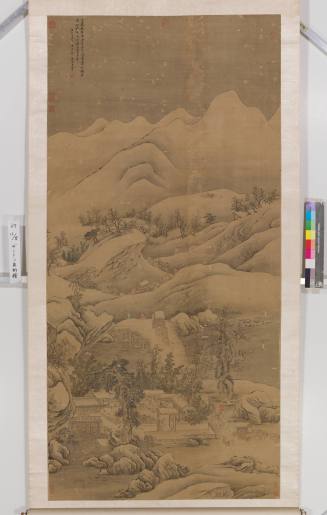

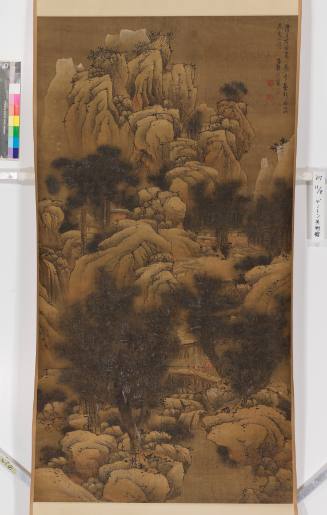

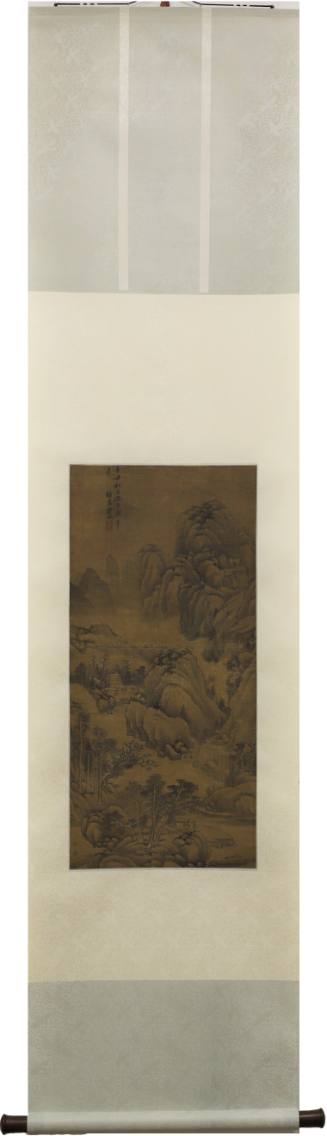

Although Wang Jian’s painting became increasingly repetitive in his later period, his eye for colour and the delicacy of his brushwork remained apparent in his most engaging work. In album leaves in the style of Zhao Mengfu (see Zhao, (1)), he reproduces Zhao’s use of yellow–orange and warm green, a variant of the warm–cool or Gold-and-green ( jinbi) idiom that in the Yuan period became popular with Southern school painters, and combines it with touches of blue and red on the foreground trees and bushes. A similar colour scheme appears in White Clouds on the Xiao and Xiang Rivers, after Zhao Mengfu (1668). This is an outstanding example of Wang’s many hanging-scroll landscapes in canonical styles, all with essentially the same composition: a river flanked by tall hills, a recession into the middle distance at one side, trees and houses, and a steep ridge rising to a central mountain. Wang notes that he once saw a Zhao Mengfu painting with the same title that ‘followed completely’ the style of Dong Yuan, this representing another step in the perpetuation of the Orthodox lineage. The power of Wang’s work relies as much on the muscular interaction of land masses as it does on the felicity and elegance of particular brushstrokes, that is on the general conception of forms, as well as their execution. The representation of the hillside in the central portion, with its serpentine ridges and compartmentalized, jutting bluff, has only enough in common with the natural world to allow recognition. In keeping with the Orthodox method, the composition is determined not by fidelity to the scenery of a specific locale but by a system of aesthetic formal rules governing placement and balance of landscape elements.

In essays on the painting of landscape by Dong Qichang, Zhao Zuo, Wang Yuanqi and others are allusions to the Chinese metaphysical concepts of geomancy ( fengshui: ‘wind and water’). A mountain, for example, is seen as a ‘dragon in motion’, with matter-energy (qi) coursing through it. Such ideas aid an appreciation of Wang Jian’s dynamic middle-ground masses, their definition and activation of ‘habitable’ space, and his contrast of a still imposing peak in the distance with the nearer shore.

Vyvyan Brunst and James Cahill. "Wang Jian." In Grove Art Online. Oxford Art Online, http://www.oxfordartonline.com.proxy.lib.fsu.edu/subscriber/article/grove/art/T090617 (accessed May 8, 2012).

Person TypeIndividual

Chinese, 1558 - 1639