Image Not Available

for Andrea Mantegna

Andrea Mantegna

Italian, 1431 - 1506

Andrea Mantegna is one of the most highly esteemed artists of his age, noted for both his profound interest and knowledge in the art of Classical Rome, as well as his technically innovative use of perspective and radical compositions. Due to the survival of significant archival material from Mantua and Padua, he is also one of the most documented artists of his generation.

At the beginning of the 15th century, Padua, along with Rome and Florence, was one of the intellectual centres of Italy. It had been annexed in 1405 by the Republic of Venice, and had in a sense become Venice's university. It was a town of intellectuals and artists who, due to the proximity of Venice, found themselves in constant touch with Greece and the East, from which ships belonging to the Venetian Republic frequently brought fragments of low reliefs and statues, which had become very popular throughout Europe with the renaissance of Graeco-Roman culture. In Padua one of the most famous collections was that of Francesco Squarcione, who later became the teacher (in 1442) and adoptive father of Andrea Mantegna.

The young Mantegna was also exposed to other treasures, such as the frescoes of Giotto in the Scrovegni (or Arena) Chapel, and Donatello's low reliefs in the Basilica del Santo, guarded by Donatello's statue of Gattamelata. These reliefs were said by André Suarez to be 'the most beautiful in the world'. Other early influences on Mantegna were works in the region that he would have studied such as the frescoes of Filippo Lippi for the Podestà's Chapel in the Basilica del Santo and Uccello's series of Famous Men at the Casa Vitaliani in Padua.

Little is known about Squarcione, Mantegna's teacher, although it is known that he had a busy painting school in Padua. At this school Mantegna must have learnt the art of adorning his madonnas with the garlands of flowers and fruit so beloved of miniaturists. However, the major influence on Mantegna's art was Donatello. The great Florentine sculptor taught him the precision of drawing and the desire to study, which, along with perspective, were Mantegna's constant concerns, and, like Donatello, he was able to breathe life into his painted statues. In 1452 or 1453 Mantegna married Nicolosia Bellini. By this time he had broken from Squarcione, declaring himself independent from him in 1448. The marriage introduced Mantegna into the Bellini family, and Mantegna became part of a long line of Venetian colourists.

The first work by the young painter was undoubtedly a piece on which Squarcione asked him to work; the decoration of Eremitani Church in Padua, which was almost totally destroyed in World War II. Mantegna started work on the Overtari Chapel in the church of the Eremitani in 1448 in partnership with Niccolò Pizzolo. They were commissioned to decorate half of the chapel. Subsequently they dissolved their partnership, and in 1453 Mantegna acquired control over the completion of the entire decoration. The work was finished around 1456. Six frescoes depicted the life of St James. The Baptism of Hermogenes reveals a precocious and surprising mastery of perspective, and its noble, sumptuously decorated architecture and deeply expressive sculpted figures became the key feature of Mantegna's work. In the Execution of St James, the landscape acquires prime importance in the composition for the first time in Mantegna's art and in the history of painting. The main scene is in the foreground, but the open landscape begins from the start of the winding path which climbs the hillside covered in towers.

Mantegna loved these escarpments, with their steep paths leading to mysterious towns, and they are evident again in the predellas of the S Zeno altarpiece: Crucifixion (Louvre), Resurrection (Musée des Beaux-Arts, Tours), and Agony in the Garden (Tours). In this latter painting in particular, Mantegna demonstrated even more clearly his skills as a landscape artist. The trees are treated with great Realism, while on the top of the hill, Jerusalem displays its towers and cupolas in the light. The four figures in the foreground may be overlooked by the observer, but the vast landscape is magisterially composed and marvellously executed. Mantegna worked on the important S Zeno altarpiece (in situ) from 1456 to 1459. Comissioned by Gregorio Correr, the abbot of the Benedictine monastery of S Zeno, it extends over three panels and reflects Correr's Christian Humanist concerns.

While Mantegna was finishing the Eremitani frescoes in Padua, he painted several versions of St Sebastian. The Aigueperse version, now in the Louvre, is particularly important, since it reveals the increasing ascendency of Humanism over medieval Mysticism. Mantegna's St Sebastian, bound to a Corinthian column, is one of the last great medieval religious figures, which were to be discarded by the artists of the Quattrocento, filled with the Paganism and sensuality of the Renaissance. Also during the 1450s, Mantegna worked on the St Luke altarpiece (1453, Brera, Milan) and other innovative works such as Presentation in the Temple (c. 1455, Gemäldegalerie, Berlin), Adoration of the Shepherds (Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York), and Agony in the Garden (National Gallery, London).

When Mantegna had finished decorating S Zeno in Verona, he went to Mantua at the behest of Marquis Ludovico III Gonzaga. The Gonzaga family was made up of lettered princes and artists, both condottieri and Humanists, who provided great hospitality to intellectuals and painters. At the Gonzaga court Mantegna produced infinitely varied works, from religious paintings to fresco portraits. In the mid-1460s, Mantegna started the decoration for the new chapel in the Castello di S Giorgio. Three works in the Uffizi are from his work there: Adoration of the Magi, Circumcision and Ascension, with a fourth, Death of the Virgin, in the Prado. This set of paintings is one of the most typical and perfect of Mantegna's works. From 1472 to 1474 he produced the frescoes for the 'Camera degli Sposi' (Bridal Chamber) in the Castello di Corte. The walls and ceiling of the bridal chamber were completely decorated, including portraits of the Gonzaga family, who are given the sculptural nobility of Piero della Francesca's figures.

Following the death of Ludovico III Gonzaga and that of his son Federico I, the successor Francesco III, a warrior rather than an artist, nevertheless continued to lavish the same favours on Mantegna as his ancestors had done. Around 1485 Francesco III commissioned Mantegna to produce the decoration for a room in the Castello Vecchio, in which theatrical performances were given. The result was Mantegna's Triumph of Caesar. Now at Hampton Court Palace, the work comprised nine parts forming a frieze of 3 metres by 27 (93/4 by 881/2 feet). This great composition is an apotheosis of movement and colour in which Mantegna used his great knowledge of archaeology, without giving in to it completely, abandoning himself to a fantasy where soldiers play the trumpet and standard-bearers, chariots, elephants and allegorical figures join in a triumphant march. Antiquity had given way to Humanism. This work was one of great significance to Mantegna, since it brought together all his aspirations.

Following its completion, Mantegna painted several religious works, such as Madonna in the Brera Gallery, and Virgin and Child Accompanied by Four Saints in the Trivulzio Collection in Milan. These later works burst with freshness. The people retain the same sculptural austerity, but the Virgin of Prince Trivulzio is framed with garlands of fruit and flowers, and her face is surrounded by a cloud of childlike faces which are angels but are close to becoming lovers.

In 1488 Mantegna was summoned to Rome by Pope Innocent VIII to paint the Belvedere Chapel in the Vatican. Although the chapel was destroyed in 1780, Vasari gives a detailed description of the work.

Mantegna became drawn more and more by youth and grace as he got older. This is evident in Parnassus (1495-1497, Louvre), which he was commissioned to produce by Isabelle d'Este for her first studiolo in the Castello di S Giorgio. This painting depicts pure Paganism, with a gentle landscape that is far from the rocky ridges of the Garden of Olives. At the peak of a rocky arch, on which stands a group of orange trees, Mars tenderly and admiringly watches Venus, completely nude, beneath the wrathful eye of Vulcan. Apollo, playing his lyre, makes the nine Muses dance around the triumphant couple, their tunics blowing in the wind, the Muses having the somewhat sentimental charm of Domenichino's nymphs.

Between 1497 and 1502, while working on Parnassus, Mantegna was commissioned by Isabelle d'Este to paint Triumph of Virtue over Vice or Pallas Expelling the Vices from the Garden of Virtue in the same pagan style. This painting is also in the Louvre and depicts an astonishing cortege of superb people and deformed, repugnant monsters.

Other late works include the altarpieces Madonna of the Victory (1495, Louvre, Paris), commissioned in response to Francesco Gonzaga's victory against the French at Fornovo, and the Trivulzio Madonna (1496, Castello Sforzesco, Milan). Devotional works dating from this period include Adoration of the Magi (1490s, Getty, Los Angeles) and Ecce Homo (Museum Jaqumart-André, Paris). Other important late works are his grisailles that simulate sculptural reliefs. They contribute to the debates about art that were contemporaneous at the time and can be interpreted as Mantegna's contribution to that debate; painting outdoing sculpture. Examples include Judith with the Head of Holofernes (late 1490s, National Gallery, Dublin), Samson and Delilah (late 1490s, National Gallery, London), and his most ambitious Introduction of the Cult of Cybele to Rome (1505, National Gallery, London).

Mantegna's last years were clouded by financial problems and worries over the behaviour of his elder son Francesco. Having made a will in favour of his son Lodovico, he requested that he be buried in S Andrea Chapel, and this request was agreed to on 11 August 1504. From that moment his health declined, and he died on 13 September 1506, aged 74, in his house in Via Unicorno, which was full of the vestiges of antiquity which he had studied passionately during his long life.

In his studio his sons found two works which are not necessarily his last ones, St Sebastian (Ca' d'Oro, Venice) and Christ, also called Dead Christ (c. 1500, Brera, Milan). This latter work is undoubtedly one of the most terrible representations of Christ, along with Grünewald's Christ in Colmar and Holbein's in the museum of Basel. Unlike Holbein's Christ, Mantegna's Christ is seen full face, cleverly foreshortened in a supreme demonstration of Mantegna's skills, and the body is stretched on a slab which evokes the dissection table. The powerful head is slightly raised and the impression of peace given by muscular relaxation immediately after death is made more evident in contrast to the faces of the two mourners. Finally, the feet and the hands bear touchingly precise wounds. It seems that the artist was disposed more towards arousing fear than emotion, and in the painting he reveals less a Christian soul than a spirit preoccupied by the possibilities of art. The schism between medieval and Renaissance religious painting had been made.

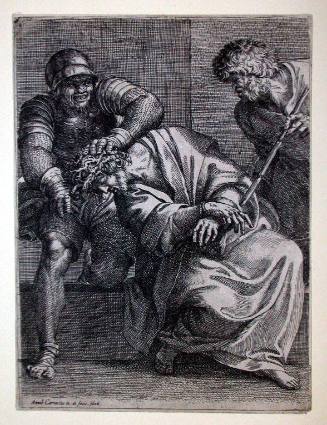

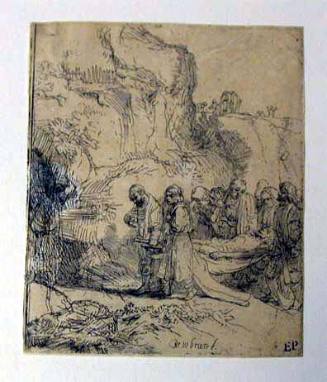

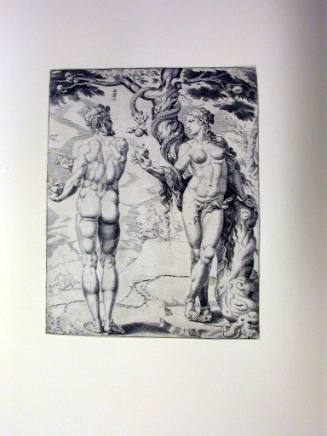

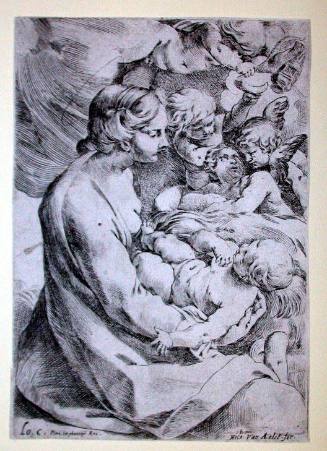

Engravings by Mantegna are rare; only seven are known.

More than any other painter, Mantegna learnt the lessons of antiquity and bore the fruits, but his genius prevented him from confining himself to a sterile erudition and allowed him to give free rein to his lyricism. He did not overlook technical concerns, but was also constantly able to work on a human level. Because of this, his Triumph of Caesar is not a cold, historical reproduction, but a manifestation of life and joy.

"MANTEGNA, Andrea." In Benezit Dictionary of Artists. Oxford Art Online, http://www.oxfordartonline.com.proxy.lib.fsu.edu/subscriber/article/benezit/B00115954 (accessed April 11, 2012).

Person TypeIndividual