Raphael Sanzio

Italian, 1483 - 1520

In Urbino, Timoteo della Viti, who had spent five years in the workshop of Francia in Bologna before settling in Urbino in 1495, showed great interest in the young Raphael and gave him advice. Raphael was barely sixteen and at his most impressionable when he joined Perugino's workshop in 1499. When he left Umbria he spent a short time in the workshop of Bernardino Pinturicchio in Siena. He then lived in Florence from 1504 to 1509, where he met the painter Fra Bartolommeo and was influenced in particular by Leonardo da Vinci. From 1509 to 1513 he was the favourite painter of Pope Julius II in Rome; then, after 1514, advisor and arranger of festivals to Leo X, and successor to Bramante in directing the work on St Peter's. Feted during his lifetime, Raphael was required to fulfil a large number of commissions, opening a workshop which drew many disciples. No doubt worn out by this huge, unremitting workload, he died of a fever at the age of just 37, leaving a great void in the art world of Rome.

As early as 1500, Raphael was commissioned by the church of S Agostino at Città di Castello to paint a Coronation of St Nicholas at Tolentino. At roughly the same time, he worked with his teacher Perugino on the Cambio building in Perugia, where his role was probably to paint the figures of Strength and Justice. In 1503, again in Perugia, he painted an altarpiece for the high altar of the church of Monteluce. To the same year belongs a Crucifixion that he painted for the church of S Domenico in Città di Castello. Soon the princely families of Urbino gave Raphael the opportunity to embark on a career as a portraitist, commissioning portraits of Guidobaldo da Montefeltro, Elizabetta Gonzaga and Emilia Pia. His Urbino period, already rich in official commissions, is also characterised by experimentation with small-scale paintings in which Raphael worked out a style which, though influenced by Perugino in its sweetness, was quite distinctive. Works such as the Three Graces or the Allegory (The Knight's Dream) (1504-1505) are characterised by a linear style, simple composition, warm colours and gentle landscapes featuring delicate trees with small, fragile leaves. He also made his mark with religious compositions in which the Virgin Mary plays the dominant role: Virgin with a Pomegranate, The Conestabile Madonna, Virgin Surrounded by Saints and above all the celebrated Marriage of the Virgin (1504), compositionally a transposition of Christ's Charge to Peter and Perugino's Marriage of the Virgin (1503-1504). Though he owed a great deal to Perugino, Raphael's composition was distinct from that of his master in its broader interpretation of space and firmer, more subtle draughtsmanship. He retained Perugino's rhythmic precision in the rendering of figures and architectural features, and also the expression of Umbrian sweetness on the face of his Virgin, which disappears in his later frescoes and in his final portraits of women.

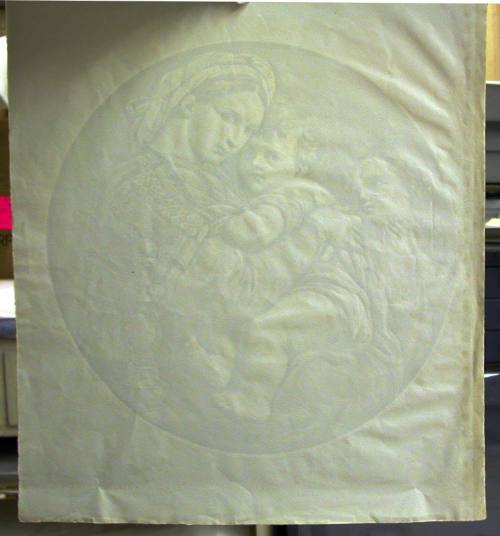

At the end of 1504, Raphael settled in Florence, where he was to remain for four years, and made the acquaintance of Leonardo da Vinci and Michelangelo. While his compositions remained simple and open, his figures were placed in sophisticated chiaroscuro as he adopted the 'sfumato' rendering that was peculiar to Leonardo, blending the contours of his volumes with the space around them, as Leonardo had learned to do from Masaccio. This resulted in a series of Madonnas which have become perhaps too well-known from being poorly reproduced on Christmas cards: the Terranuova Madonna (1505); the Madonna del Gran Duca (c. 1505); the Belvedere Madonna (1506); the Madonna of the Goldfinch (c. 1506); La Belle Jardinière (1507) and the Canigiani Holy Family (c. 1507). In most cases, drawing inspiration from Leonardo, Raphael based his composition on a pyramid, with the Virgin's head at the apex, eyes lowered to watch the infant Jesus and St John at the base, and sometimes with St Elizabeth and St Joseph completing the construction. Through these Madonnas, Raphael worked out a notion of pure, sublime beauty, while avoiding sentimentality.

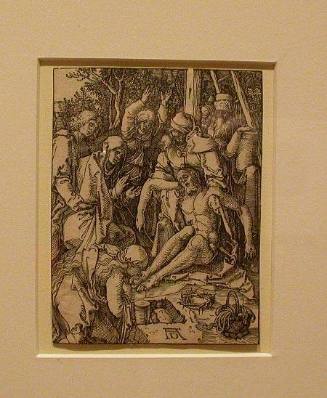

As well as developing this style with its accent on gentle beauty, Raphael tried his hand at more complex compositions, such as the Deposition or Entombment ordered in 1507 for the Baglioni family chapel in S Francesco al Prato, Perugia. In this case, dramatic intensity is generated by the twisted attitude of the bodies and the tension on the faces; the style is very similar to that of Michelangelo, but adapted in pursuit of his own ideal. During his Florentine period, Raphael showed a degree of vigour in his portraits, which stand out against increasingly abstract backgrounds, as evidenced by his portrait of Maddalena Doni (1506). This tendancy would come to full fruition ten years later in his portrait of Balthazar Castiglione (1514-1515), painted on a plain background.

In 1509 Raphael moved to Rome, summoned by the papal architect Bramante, also a native of Urbino, who was also behind Michelangelo's move to Rome. At the time the city was undergoing a complete transformation at the instigation of Julius II, the warrior pope who was also a great lover of the arts. Rome inspired in Raphael a new strength; and though the various influences on him all contributed to his mature style, the result transcended the sources. Despite the fact that he was barely 26 when he arrived in Rome, he was entrusted with the task of decorating the Stanze, the pope's private apartments in the Vatican Palace. Between 1508 and 1511, he worked on the Stanza della Segnatura, decorating it with scenes of The Dispute concerning the Holy Sacrament (La Disputa), also known as The Triumph of the Eucharist; The School of Athens; Parnassus; The Virtues; Tribonian Delivering the Pandects to Justinian; and Gregory IX Receiving the Decretals from St Raymond de Penafort. From the second half of 1511 to 1514, he worked on the Stanza d'Eliodoro: Heliodorus Ejected from the Temple; The Mass at Bolsena; The Liberation of St Peter; and The Meeting between Attila and Leo the Great. The frescoes painted between 1514 and 1517 in the Stanza dell'Incendio were mostly done by Raphael's assistants, in particular Giulio Romano, Gian Francesco Penni and Raffaellino del Colle.

In these mural decorations we see a distinct change in Raphael's style, which also reflects the wider progression in 16th century Italian art from the Renaissance to the Baroque. This is clear from a comparison of The School of Athens (1509-1510) in the Stanza della Segnatura, with Heliodorus Ejected from the Temple (1512-1514), in the Stanza d'Eliodoro. The two works are similar in composition, based on a series of arches which lead the eye into the distance. However The School of Athens has a number of distinct planes, with the figures standing out clearly against a light-coloured background. Those in the foreground are arranged in a balanced, almost symmetrical way in relation to one another, while the heads of those in the second rank are practically in line. The composition is also linear in its architectural features, with flat pilasters giving an even rhythm to the buildings. A sense of depth is created by the lines in the paving, in the bottom part of the picture, and by the little table on which Heraclitus (who has the features of Michelangelo) is writing. Heliodorus Ejected from the Temple could almost have been painted by another artist: everything stands out in relief due to chiaroscuro effects. It is the alternation of light and shadow which leads the spectator's eye from one cupola to another towards the boundless sky. The groups of figures located here and there are sculpted by the light, which throws their muscles into relief, while the floating draperies accentuate their agitated movements. This style of composition heralds Baroque art, even in its architectural details: instead of flat pilasters, we find engaged columns, thrown into relief by the chiaroscuro. There is no sculpture, but a figure perched on and attached to one of these columns, creating a confusion between relief and living being - an entirely Baroque feature. Raphael's style in this work is akin to that of Michelangelo, to whom he is traditionally opposed as if they were rivals, and he had undoubtedly been influenced by his contemporary's Sistine Chapel ceiling, completed in 1512.

Raphael is the master of the arabesque, of lines which meet and intermingle. In Parnassus, the groups of women are so arranged that their heads incline one towards another, while their gestures balance one another in a musical rhythm. Raphael adapted his forms to the surface he was required to decorate, harmonising greys and reds, greens and blacks, lilacs and silvery whites. In The Mass at Bolsena, he demonstrates all these skills: the composition frames a window, the colours are rich, the texture of the fabrics is rendered with great flair - a difficult feat in fresco, which tends to give chalky tones. As a result, line, mass and colour were united for the first time, which is why Raphael has had such a great influence on modern European painters.

Raphael's genius was not restricted to painting, but also found expression in architecture. Not long after 1509, he drew up plans for the church of S Eligio degli Orefici in Rome. One of his great admirers was the banker Agostino Chigi, who first commissioned a fresco of the Triumph of Galatea (1511) for his villa, the Farnesina, then asked Raphael to design stables for it (1512). Raphael also built and decorated a funerary chapel for Chigi in the church of S Maria del Popolo (1512-1513). On Bramante's death in 1514, Pope Leo X appointed Raphael architect of St Peter's and curator of antiquities, with the task of purchasing Classical items for the Vatican. According to Vasari, he drew up plans for a number of villas and palaces, including the 'Vigna del papa', later known as Villa Madama when it became the property of Margaret of Austria. In 1516-1517, he designed the decoration for the loggia of the Palazzo Farnese, taking the myth of Psyche as his theme. At roughly the same time, between 1515 and 1518, he created some tapestry cartoons for the Vatican. He even designed a bathroom, or stufetta, for Cardinal Bibbiena in 1516.

The great quantity and diversity of Raphael's activities explains why he was unable to execute personally the major decorative projects he was asked to undertake. He had to mobilise his entire workshop or bottega, working to his strict instructions, particularly for the decoration of the Vatican loggias which had been begun by Bramante. For this highly complex project, carried out between 1517 and 1519, he developed a whole system of grotesque and trompe-l'oeil effects. Featuring bright colours, the work was performed with flair, elegance and lightness of touch, in a style totally opposed to that of Michelangelo.

When he wrote to Castiglione: 'To paint a beauty, I need to see a number of beauties, but since beautiful women are very rare, I use a certain idea which I have in my head', Raphael was defining his ideal of beauty, which is impossible to find in nature but which he expressed in a work such as The Triumph of Galatea (1511) in the Palazzo Farnese. In this composition, harmonious and tormented lines correspond; light colours, which emphasise the freshness of Galatea's body, contrast with the dark, floating fabric which surrounds her. This balance is repeated in the Vision of Ezekiel (1516-1518), with its bold foreshortenings and flaming colours, which prefigure one of Raphael's last works, The Transfiguration (1518-1520). Here, religious intensity is boldly expressed in a composition whose upward, rising movement is conveyed by bright shafts of light. The painter seems to have made the transition from Mannerism, in the lower part of the picture, to the Baroque, in its upper regions.

Though the quest for ideal beauty would seem to be fundamental to Raphael's work, as suggested by his Madonnas, the desire to render human personality with truth and sensitivity is evident in his portraits of a lively-featured Cardinal (1510-1511); Julius II (1511-1512), an old man bent under the burden of his heavy responsibilities; and Leo X (c. 1518), the self-confident epicurean. It also comes across in his portraits of his friend Balthazar Castiglione (1514-1515), with his kind, intelligent expression, and the Lady with a Veil (La Velata) (1516), whose inner feelings he has rendered so poignantly. In the portrait of his companion, La Fornarina (Borghese Gallery), he even conveys overt sensuality, barely concealing the charms which so entranced him.

Raphael achieved the near-impossible in assimilating the styles of Perugino, Leonardo and Michelangelo, then transcending them. His use of line may at times seem bland, but is nonetheless firm and capable of expressing tension. In his use of colour, his predilection is for soft, warm tones, generally light in character, or for the acid colours typical of the Mannerists. His compositions, which always show a love of balance, even in movement, tend towards the Baroque. His style, which played a vital part in the overall development of Western art, has been unreservedly appreciated and admired by traditionalists, though rejected by those who by the mere fact of choosing to call themselves 'Pre-Raphaelites' demonstrate the great significance they ascribe to him.

In 2001, the Staatgalerie in Stuttgart exhibited a collection of drawings by Raphael and prints engraved during his lifetime and after his death, while the Musée du Luxembourg in Paris staged a show of his major paintings and drawings on the theme of portraiture, entitled Raphael: Grace and Beauty (Raphaël. Grâce et Beauté). In 2003, the Palais des Beaux-Arts in Lille exhibited the Italian drawings in its collection under the title Raphael and his Time (Raphaël et son temps).

"RAPHAEL." In Benezit Dictionary of Artists. Oxford Art Online, http://www.oxfordartonline.com.proxy.lib.fsu.edu/subscriber/article/benezit/B00148927 (accessed April 12, 2012).

Person TypeIndividual