Heinrich Aldegrever

German, 1502 - c. 1561

German engraver, painter and designer. He was the most important graphic artist in Westphalia in the 16th century. His reputation rests largely on his ornamental designs, which make up about one third of his c. 300 engravings. They were principally intended as models for metalworkers but were also adapted by other craftsmen for such decorative arts as enamel, intarsia and book illustration. Aldegrever followed Dürer and the Nuremberg Little Masters, deriving models for his paintings and subject prints as well as a full repertory of Renaissance ornamental motifs: fig and Acanthus foliage, vases and cornucopia, combined with putti and satyrs, tritons, mermaids and dolphins, sphinxes, masks and medallions. From the beginning of his career Aldegrever was aware of the artistic trends of the time: the Dürer influence was strongest at its outset yielding somewhat in work of the 1530s to Mannerist tendencies under Netherlandish influence, though never waning entirely.

1. Early work, 1527–30.

Aldegrever was the son of Hermann Trippenmeker (d 1545) from Paderborn. The year of his birth is calculated from two dated engraved self-portraits (b. 188–9) of 1530 and 1537 giving his age as 28 and 35 respectively. He was married and had two children, a daughter and a son, Christoph (fl 1553–61), who became a goldsmith. After an initial apprenticeship as a goldsmith, Heinrich Aldegrever trained as a painter, probably in Soest, judging by the typically Westphalian Late Gothic traits of his early work. He probably spent some of his time as a journeyman in the Netherlands, rather than in Nuremberg as has been proposed. He settled in Soest c. 1525, became a master and guild member soon after and a citizen in 1530.

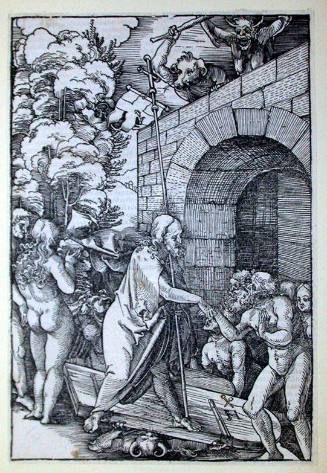

For the church of St Peter, Soest, Aldegrever painted the wings and predella of an altarpiece (1526–7; Soest, S Maria zur Wiese) with a Virgin in Glory and SS Agatha and Anthony on the outside and a Nativity and Adoration of the Magi on the inside, based on Dürer’s Life of the Virgin (b. 77). The inside scenes are repeated on the outer predella with an added Annunciation, while its inside features six Apostles. This panel bears the signature ht for Heinrich Trippenmeker (Ger.: ‘maker of clogs’), while the Nativity shows a clog as signature above a shepherd (Aldegrever’s self-portrait), who looks out at the viewer. From 1527 Heinrich used the name Aldegrever consistently and signed his works ag, shaped like Dürer’s famous monogram. The altarpiece was one of the last large church commissions in Westphalia before the Reformation spread to northern Germany.

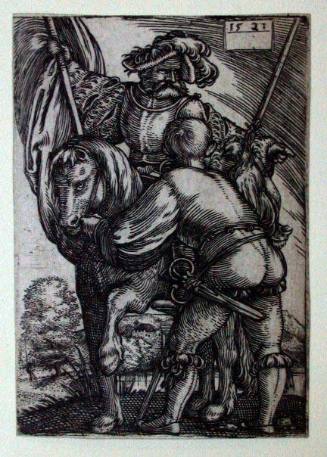

One quarter of Aldegrever’s ornamental prints bear monograms but no dates. Some vignettes of simple symmetrical design predate four lively engravings (1527) that are technically and structurally more advanced. In 1528 Aldegrever first employed the vertical format, employing pilaster decorations, and he produced his first paired dagger-sheath designs, with a Standard-bearer (b. 225) and the Whore of Babylon (b. 226) atop rising foliage patterns. He used the same principle of horizontal division for two sheaths (1529) representing David with the Head of Goliath (b. 234) and an Executioner with the Head of John the Baptist (b. 235).

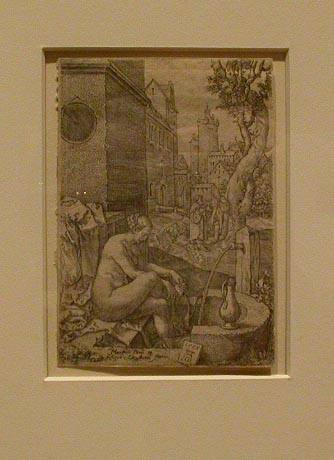

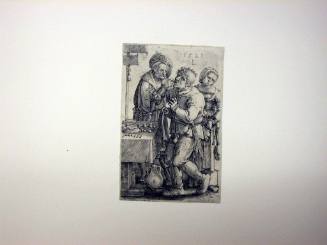

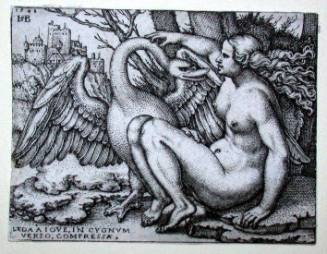

The models for a set of five very small engravings of the Virgin and Child (1527; b. 51, 53–56) are those that Dürer (b. 32, 37–9) engraved between 1516–20, and a St Christopher (1527; b. 61) closely follows Dürer’s print (b. 52) in composition and in minor details. In a half-length Judith with the Head of Holofernes (1528; b. 34) Aldegrever employed the profile view, popular in Italian Renaissance portraiture. Two small representations of Samson and Delilah (1528; b. 35–6), The Lovers (1529; b. 73) and a few other early prints were designed in tondo form. These themes and Lot and his Daughters (b. 13–17), inspired by Dürer’s St Anthony Reading, allude to the Power of Women, a favourite conceit of the time and often addressed by Lucas van Leyden. Subjects from Greek and Roman antiquity were also introduced early (1529) with Medea and Jason (b. 65), Hercules and Antaeus (b. 96) and Mutius Scaevola before Porsena (1530; b. 69). In these prints Aldegrever demonstrated familiarity with Renaissance décor and contemporary proportion studies. Technically and compositionally the most accomplished work of this period is a Landsknecht with Brazier and Bucket (1529; b. 174); the Self-portrait (b. 188) is relatively tentative in its perspective and hatching. Aldegrever tried the new medium of etching, not very successfully, in 1528 with an Orpheus and Eurydice (b. 100), a Standard-bearer (b. 176) and a Portrait of a Man Crowned with Vine Leaves (b. 187). A good woodcut of Pyramus and Thisbe (Hollstein, v. 1, no. 143) dates to the same year.

2. Mature work, 1531–41.

Soest became a Protestant community in 1531, and Aldegrever embraced the new faith wholeheartedly. This is evident from the subjects he engraved, including the Monk and Nun (1530; b. 178), which is a reverse copy after Georg Pencz. With diminishing demand for sacred art, Aldegrever concentrated on engraving such secular subject-matter as landsknechts, dancing couples and genre scenes, portraits, allegories, mythological scenes and Old Testament stories, in the wake of Luther’s translation of the Bible (see fig.). Given his Lutheranism, it is surprising that, in 1536, he executed major engravings of the imprisoned Münster Anabaptist leaders Jan van Leyden (b. 182) and Bernard Knipperdolling (b. 183) for the Bishop of Münster. He represented van Leyden, the leader of the group, not as an ignominious figure but as a dignified and forceful man. All the ennobling trappings of a Renaissance portrait are present; his insignia are carefully rendered, and an explanatory Latin inscription on a plaque fastened to a parapet includes the artist’s name and home town. The engraved portraits of Martin Luther and Philip Melanchthon (both 1540; b. 184–5) are rather eclectic, while those of the Anabaptists, the Self-portrait (b. 189) and that of Duke William V of Jülich-Kleve-Berg (1540) are of high quality. The vivid portrait of Graf Philip III Zu Waldeck (1537; Arolsen, Residenzschloss) is the only correctly attributed painting of this period.

The change to a Mannerist style during the middle period of Aldegrever’s career is evident in the engraved series of the Story of Joseph. Whereas three scenes, Joseph Explaining his Dreams to Jacob (b. 18), Joseph and Potiphar’s Wife (b. 19) and Potiphar’s Wife Accusing Joseph (b. 20), were executed in 1532, the last scene, Joseph Selling Wheat to his Brothers (b. 21), is earlier and is dated 1528. In the later prints the figures are elongated and their heads have become appreciably smaller, an impression emphasized by the replacement of Joseph’s broad-rimmed hat in the print of 1528 by a small cap in the others. There is also a notable change in tonality from a more even lighting to greater contrasts between dark and light. In Bathsheba in her Bath (b. 37), Rhea Silvia (b. 66) and Marcus Curtius (b. 68; all 1532) Aldegrever depicted muscular nudes in various twisted, Mannerist poses. The elongation is more pronounced in the series of Gods who Preside over the Seven Planets (1533; b. 76–82), as the figures fill the frames from top to bottom; in the case of Luna (Diana; b. 81), Jupiter (b. 78) and Saturn (b. 80) the crowns of the heads are cropped.

From 1534 to 1536 Aldegrever concentrated on ornamental designs, returning to the nude in 1538 with the minute frieze of Hannibal Fighting Scipio (48×215 mm; b. 71), which contains no fewer than 26 men, and a Judgement of Paris (b. 98). In the same year he produced two sets of Wedding Dancers, one comprising eight engravings (b. 144–51) in postage stamp size (54×36 mm), the other with twelve (b. 160–71) twice as large (117×56 mm). Their main importance rests in their technical excellence and their documentary value for the history of costume and dance. A set of Four Evangelists (1539; b. 57–60) follows Pencz once more. Aldegrever reached the climax of his Mannerist style in two series dated 1540, the Story of Adam and Eve (b. 1–12) and the Story of Amnon and Tamar (b. 22–7). The figures no longer fill the entire picture space but are embedded in landscapes and interiors. The Power of Death suite (1541; b. 135–42) includes scenes with a pope, cardinal, bishop and abbot as Death’s victims.

The ornamental works include horizontal designs for three single scabbards (1532) with a pair of Dancers (b. 247), a Nude Couple (b. 248) and a Soldier Embracing a Nude Woman (b. 249). Four more undated sheaths (b. 213–16) with single figures, with Mannerist, elongated figures and drapery style, were made later. Particularly rich and sophisticated are three designs (1536; b. 259, 1537; b. 265, 1539; b. 270) for daggers with scabbards that are proportionally partitioned by swellings. The spiral and fluted column motifs at their points, the decoration with profile heads in medallions as well as the unity of patterns and the articulated, symmetrical composition are clearly inspired by Italian ornament engravers. The same full-blown Renaissance style is evident in engraved models for three brooches (1536; b. 258), a buckle (1537; b. 263) and two crossed folding spoons that could also be used as whistles (1539; b. 268). At this time Aldegrever also executed a number of fashionable putti friezes (b. 252, 257, 262).

3. Final work, 1541–55.

After an unexplained lacuna in his oeuvre from 1541 to 1549, Aldegrever produced relatively few single engravings. A series of 14 Allegorical Figures (1549–50; b. 103–16) displays a new affection for fancily creased, billowing draperies that tend to move independently of the bodies they cover. But in two related sets of Virtues (b. 117–23) and Vices (b. 124–30) dated 1552 these features are exaggerated, and the prints are inferior in composition and technique. Another group of small Wedding Dancers (1551; b. 152–9) suffers from the same weaknesses, hiding bodies under masses of crumpled garments and rendering movements incomprehensible. Of much better quality are the Twelve Labours of Hercules (1550; b. 83–95): the bodies of the hero and his antagonists are well proportioned and solid, movements are articulated and tonal values balanced. The designs may have an Italian model.

Aldegrever’s last works employ biblical subject-matter. The Lazarus (b. 44–8) and Good Samaritan (b. 40–43) series (both 1554) use horizontal format to accommodate the large number of figures that are successfully integrated within complex surroundings; the more solid types in the Good Samaritan series emerge with greater clarity, while those in the Lazarus prints dissolve in a glitter of light and dark spots. This scintillating effect of rumpled garments and hair is a hallmark of Aldegrever’s late works. In the Story of Susanna (b. 30–33) and the Story of Lot (b. 14–17), both dated 1555, he displayed for the last time his technical virtuosity and excellent craftsmanship, his expert treatment of even the smallest detail.

A small panel of Lot and his Daughters (1555; Budapest, N. Mus.) is the only authentic late painting. The late ornamental prints depict grotesques and attempt the compact organization of forms into cohesive relief strata, but Aldegrever overloaded the designs with excessive detail and patterns, resulting in a loss of clarity and vitality. His late pieces were old-fashioned, in that they did not include the newly popular elements of scrollwork and arabesque. His main influences at this time were Zoan Andrea, Marcantonio Raimondi and Raimondi’s assistants, Agostino dei Musi and Marco Dente. The influence of Dürer was still present, however. Aldegrever’s Fortune, dated 1555 (b. 143), retains the essential elements of Dürer’s Large Fortune (b. 77).

Rosemarie Bergmann. "Aldegrever, Heinrich." In Grove Art Online. Oxford Art Online, http://www.oxfordartonline.com.proxy.lib.fsu.edu/subscriber/article/grove/art/T001636 (accessed April 27, 2012).

Person TypeIndividual

German, c. 1482 - 1539/40