George Morland

English, 1763 - 1804

(not assigned)England, United Kingdom, Europe

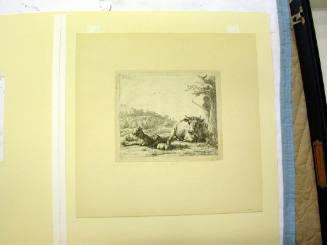

BiographyBorn London, 26 June 1763; died London, 29 Oct 1804.Son of Henry Robert Morland. He first exhibited chalk drawings in 1773 at the Royal Academy; his father recognized his precocious talent and bound him apprentice for seven years from 1777. Morland’s chief employment during this period lay in copying and forging paintings, particularly 17th-century Dutch landscapes, although he also made a number of sea-pieces after Claude-Joseph Vernet. The excessive discipline imposed upon him during his apprenticeship may have inspired the libertarianism and disregard for social convention that characterized his later years. Although he entered the Royal Academy Schools, his attendance was sporadic; he preferred to frequent alehouses, such as the Cheshire Cheese in Russell Court.

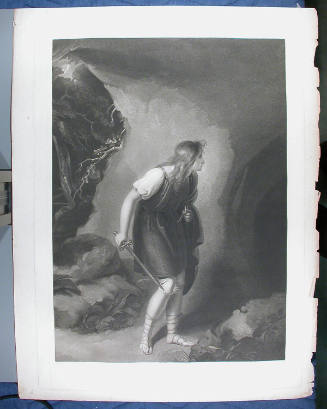

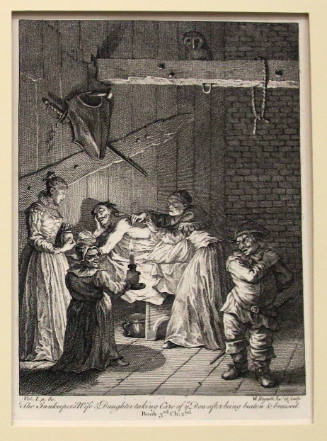

In 1780, the year the engraver John Raphael Smith published prints after Morland’s the Angler’s Repast and a Party Angling, George Romney offered Morland a three-year apprenticeship, but this he refused. In 1781, without his father’s knowledge, Morland began working for an Irish dealer in London, who paid him only enough to ensure his continued dependence. When Morland’s apprenticeship ended in 1784, he moved from the family home; the following year he was living in Margate, Kent, having been taken up by a Mrs Hill, whom he also accompanied on a trip to France. By the spring or early summer of 1786 he was back in London, exhibiting at the Royal Academy that year. In September he married Anne, a sister of the engravers William and James Ward, both of whom had trained under Smith. At this period in his career Morland was producing sentimental genre pictures in the manner of Francis Wheatley; the moralizing thrust of many of them derived ultimately from William Hogarth as, for example, in the Idle Mechanic and the Industrious Mechanic, or the Idle Laundress, which William Blake engraved in 1788.

By 1787 Morland was displaying what was to become a characteristic restlessness, while selling his works to the dealers through a middle-man named Irwin. He preferred the independence of disposing of his finished pictures through dealers rather than seeking out commissions, even declining an invitation to supply Carlton House with ‘a room of pictures’ for the Prince of Wales (later George IV). According to Dawe (1807), ‘the reasons Morland assigned for disliking to work for gentlemen were, his choosing not to accommodate himself to the whims of his employers’. By this time Morland was rapidly becoming a popular artist. In 1788 alone 33 of his paintings were engraved and published, worked on by no fewer than 11 engravers, but his continued profligacy was beginning to get him into serious debt. He engaged a lawyer to look after his interests and in 1789 is thought to have made the first of several trips to the Isle of Wight in order to evade his creditors. When in London he moved lodgings regularly, for a while living opposite an inn at Paddington, which supplied him with low-life subject-matter. He also began to take on pupils for financial reasons. One such student, David Brown, who at the age of 35 had sold his business in order to article himself to Morland, bought Morland’s the Farmer’s Stable (London, Tate) for 40 guineas, exhibited it at the Royal Academy in 1791 and then sold it for 100 guineas, receiving at the same time 120 guineas for Morland’s the Straw Yard.

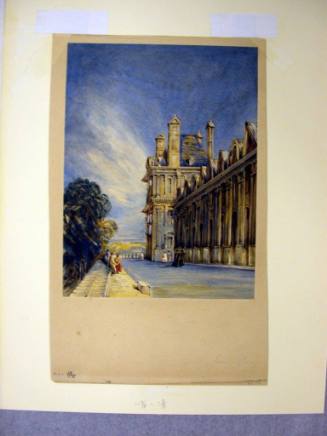

From c. 1790 Morland began working on larger canvases, producing the very large number of rustic and smuggling scenes with which he is particularly associated. His paintings of the early 1790s, generally considered his best, are designed and finished with some care; later works show signs of being hastily executed pot-boilers. When broke he could paint a saleable picture at phenomenal speed (two and a half hours has been recorded; see Gilbey and Cuming, pp. 215–16), and if he was pressed too hard by his creditors he simply disappeared into the country. This enforced familiarity with rural life informs such anecdotal pictures as the Benevolent Sportsman (exh. RA 1792; Cambridge, Fitzwilliam), commissioned by a Colonel Stuart and engraved by Joseph Grozer (b c. 1755) in 1795. Other representative works from this period include Gypsies around a Camp Fire in a Wooded Landscape (Bristol, Mus. & A.G.), Morning: Higglers Preparing for Market (1791; London, Tate) and the Tavern Door (Edinburgh, N.G.). In 1792, while Morland was once again in hiding from creditors (possibly in the Lake District), the dealer Daniel Orme opened an extremely successful Morland Gallery in Bond Street, London, with over one hundred of Morland’s works on sale. Morland, meanwhile, continued to paint, sending works to the capital with his servant. Around 1793 Smith also opened a temporary Morland Gallery in London, issuing A Descriptive Catalogue of Thirty-six Pictures Painted by George Morland, all of which he intended to engrave and publish by subscription.

Although Morland was back in London in 1793, by this time his marriage was in difficulties and he spent regular periods away, often in the company of gypsies. Various arrangements were made to help him meet his debts, but despite the ready market for his works, now often sold through Henry, his brother, Morland was eventually arrested for debt. He soon regained his freedom but for the rest of the decade his life was largely spent on the run, holed up in confined quarters. His work, nevertheless, was still popular with engravers and the public: 13 prints after his works were published in 1797, a year in which he sent seven pictures for exhibition at the Royal Academy. In April 1799 he and his wife went to the Isle of Wight in order to evade bailiffs, but he was back in London by November. In December he was arrested for debt and imprisoned, being freed by legal amnesty in 1801. Despite his chronic alcoholism Morland’s output towards the end of his career was staggering—he is reputed to have painted some 800 pictures in the last eight years of his life. Friends continued to help him, but after his further arrest for debt in October 1804 he appears to have drunk himself into a terminal coma.

Morland’s technique was assured; he painted in the light and fluid manner of such contemporaries as Wheatley and Julius Caesar Ibbetson, but stylistic reminiscences of Dutch masters and Thomas Gainsborough are also apparent. Although his work appears at first to fit comfortably within the idiom of sentimental rural genre, closer inspection reveals much of the class tension of the period and the subliminal propaganda that underlay the production and reception of rural imagery: the mounted figure in the Benevolent Sportsman, playing his allotted role, gives alms to gypsies who assert their domestic independence on common land at a time when much of it was being appropriated by landowners for their own agriculture or sporting pursuits. In addition, Morland’s celebration of alehouses disturbed more conservative tastes, and some of his female figures appeared to some to be too wanton, when compared with the usual, more stereotypical, rural nymphs. On occasion, engravers chose to make their prints more attractive to potential customers by transforming into willing and smiling faces the often expressionless features of Morland’s rural proletariat. In 1793, for example, James Ward made just such adjustments when preparing his Sunset: A View in Leicestershire, a print he based on Morland’s painting the Door of a Village Inn (London, Tate). Prints made after Morland’s works, most of which were executed in mezzotint, were sold at prices ranging from 3s. 6d. to one guinea. The large market that existed for them in Britain, and in France and Germany as well, made his name everywhere known, and helped generate the rash of anecdotal biographies that swiftly appeared after his death.

Hugh Belsey and Michael Rosenthal. "Morland." In Grove Art Online. Oxford Art Online, http://www.oxfordartonline.com.proxy.lib.fsu.edu/subscriber/article/grove/art/T059661pg2 (accessed May 1, 2012).

Person TypeIndividual