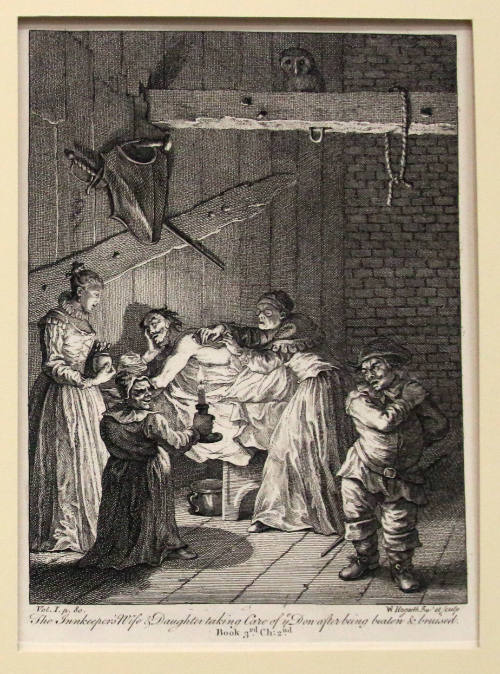

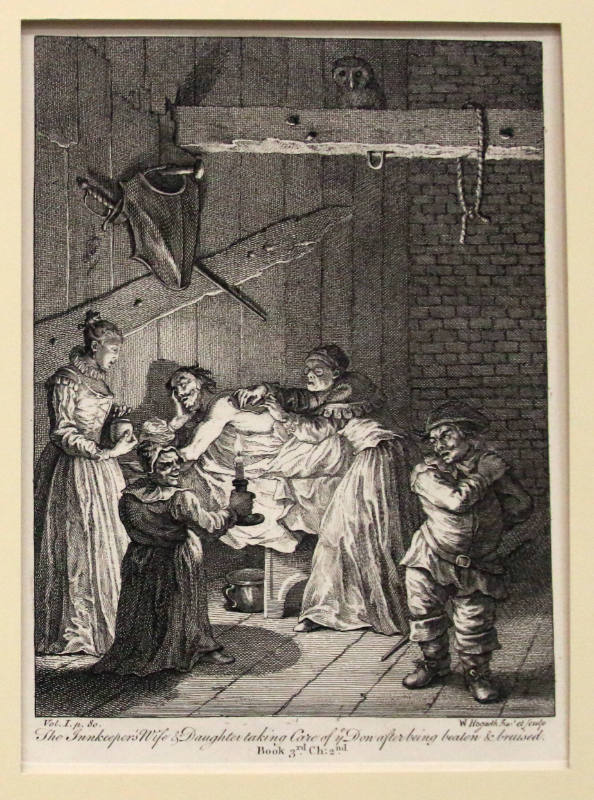

William Hogarth

British, 1697 - 1764

Contemporary drama and novels provided Hogarth with analogies for the composition of his ‘modern moral subjects’ (his own phrase). These were series devised in six or eight scenes unfolding in each case a cautionary tale of vanity, corruption, and betrayal leading to decline and death. Strikingly inventive and filled with vivid characterizations and a wealth of detail, they were instantly popular, in their engraved form, and they remain Hogarth's most famous works. The first was A Harlot's Progress (1731; paintings lost; engraved 1732), followed by A Rake's Progress (1733–4; London, Soane Mus.; engraved 1735). Then came the more ‘upmarket’ Marriage à la Mode (1743; London, NG; engraved 1745), for which Hogarth employed a more refined style of painting and hired specialist French engravers. Afterwards he adopted a more directly didactic approach, used engraving only, and aimed for a lower-class audience. He did this in Industry and Idleness (1747), Beer Street and Gin Lane (1751), and the Four Stages of Cruelty (1751). Finally, in 1754–5, he reverted to the satirical mode and to painting in the four scenes of The Election (London, Soane Mus.).

Another, different expression of Hogarth's wish for the improvement of society was his interest in hospitals. In 1736–7, he painted, without fee, the staircase walls of St Bartholomew's Hospital, close to where he had been born, with appropriate biblical scenes in a high Baroque style. He was also a keen supporter of the Foundling Hospital, inaugurated in 1739 by Captain Thomas Coram. For this institution, he portrayed Coram seated full-length, in the Grand Manner (1740), contributed two other paintings of his own, and persuaded other artists to present pictures—with the result that the hospital both benefited from the sale of admission tickets and became a showcase for contemporary British painting. (All the paintings still hang in the administration block of the Foundling Hospital, London, although the hospital itself no longer exists). As this venture shows, Hogarth was far from being only a popular recorder of the seamier side of London life. He was deeply concerned about the prospects for the artistic profession in Britain, which he felt was held back by lack of patronage, other than for portraiture, and he was an original if somewhat muddled thinker about the problems of high art. In 1735, he had founded a second academy in St Martin's Lane and ran it for 20 years as a centre of lively discussion as well as professional practice, much of the former being reflected in his treatise The Analysis of Beauty (1753).

Kitson, Michael. "Hogarth, William." In The Oxford Companion to Western Art, edited by Hugh Brigstocke. Oxford Art Online, http://www.oxfordartonline.com.proxy.lib.fsu.edu/subscriber/article/opr/t118/e1219 (accessed May 1, 2012).

Person TypeIndividual