Abraham Janssen van Nuyssen

Flemish, 1575 - 1632

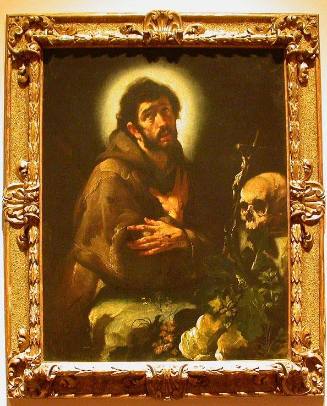

Flemish painter. He painted historical, religious and mythological subjects, often on a large scale, derived principally from antique sculpture and the art of Michelangelo and Raphael and, to a lesser degree, from certain contemporaries, including the Dutch late Mannerists and the Bolognese school. He was highly esteemed in Antwerp but suffered, then and subsequently, from the inevitable comparison with his contemporary and formidable rival Rubens, whose brilliance somewhat eclipsed his own achievements.

1. Life and work.

(i) Training and early career, to c. 1608.

In 1584–5 Janssen was apprenticed in Antwerp to the painter and art dealer Jan Snellinck I. By that time his father, Jan Janssen, had died, and his mother, Roelofken van Nuyssen (whose name he embodied in his signature), had married the Antwerp schoolmaster Assuerus Boon, a fairly well-off man with artistic and intellectual contacts. Thus Janssen’s family circumstances and training provided a good basis for his career as a history painter, though it did not compare with that of Rubens. Janssen subsequently completed his training in Italy. He was recorded in Rome on 5 August 1598, and again on 26 March 1601 as a pupil of the Dutch painter Willem van Nieulandt I. At this time Janssen painted Diana and Callisto (1601; Budapest, Mus. F.A.). The figures, whose softness is strongly reminiscent of those of Jan Snellinck, are set in a wooded landscape, with still-life elements in the Flemish tradition. However, the conception of beauty, the poses, the draperie mouillée and the elaborate hairstyles already reflect Janssen’s fascination for antique and Renaissance sculpture, which was to influence his work strongly. In addition to free borrowings from the Classical sculpture known as the Spinario at the centre (see [not available online]) and Michelangelo’s Night (c. 1522; Florence, S Lorenzo) on the right, the nymph on the extreme left is an exact copy of the Classical Nymph with a Shell (Paris, Louvre), which was in the Villa Borghese, Rome, as late as 1638.

Janssen returned to Antwerp c. 1602 and became a master in the Guild of St Luke. On 5 May 1602 he married Sara Goetkint, whose family was active in the art trade. Janssen’s rising professional status was recognized by his appointment as senior dean of the guild in 1607–8, making it unlikely that he made a second journey to Italy, as is often claimed. Before 27 May 1603 Janssen completed the inside panels of a triptych with the Virgin of St Luke (Mechelen Cathedral) for the painters’ guild in Mechelen, to replace the altarpiece by Jan Gossart and Michiel Coxcie (Prague, Hradc(any Castle). The central panel is clearly an artistic response to the similar work that Marten de Vos, then highly influential among painters in Antwerp, had executed a year earlier for the Guild of St Luke. Also from this period are a number of works, rightly attributed to Janssen, signed with a monogram that has been read as AJ or AB; in the latter case it may stand for Abraham Boon, by which name (his stepfather’s) he is referred to in a surviving document. Historically, the most important of these works is perhaps Hercules Expelling Pan from Omphale’s Bed (1607; Copenhagen, Stat. Mus. Kst), in which Janssen is seen to have initiated in Antwerp a highly erotic genre, inspired primarily by Agostino Carracci’s prints known as Le Lascive (c. 1590–95; b. 114, 123–36).

(ii) Rivalry with Rubens, c. 1608 and after.

Janssen’s position as one of the most important history painters in the Netherlands was challenged by Rubens’s return to Antwerp in 1608. The former’s fame was not immediately eclipsed, however: between 1608–9 and 1618–19 both artists supplied paintings for three known ensembles. The first, rightly regarded as a masterpiece by Janssen, was Scaldis and Antwerpia (the ‘Scheldt and Antwerp’, 1610; Antwerp, Kon. Mus. S. Kst.), an overmantel that, together with Rubens’s Adoration of the Magi (Madrid, Prado), adorned the state room of the Antwerp Stadhuis during the negotiations with Spain that resulted in the Twelve-year Truce (9 April 1609). In its iconography and composition, this allegory is an ingenious transposition of Michelangelo’s famous Creation of Adam (Rome, Vatican, Sistine Chapel): the vital contact between God the Father and Adam is paralleled by the cornucopia that the expectant maid, representing Antwerp, receives from the River Scheldt, her economic lifeline. One may wonder whether such an impressive work did not influence Rubens’s painting in the period immediately following: there are, for example, similarities with his Samson and Delilah (c. 1609–10; London, N.G.; see [not available online]), such as the colour of the garments of the female protagonists.

Five years later Janssen and Rubens each painted an overmantel for the Antwerp Stadhuis, this time for the assembly hall of the Oude Voetboog (Old Crossbowmen), the city’s chief militia company. In contrast to Rubens’s Triumph of the Miles Christi (1614; Kassel, Schloss Wilhelmshöhe), Janssen’s Peace and Plenty Binding the Arrows of War (the ‘Allegory of Concord’, 1614; Wolverhampton, A.G.) adheres strictly to the conventions of Cesare Ripa’s Iconologia, thus illustrating the distance between Janssen and Rubens’s erudite use of sources. The limitation of Janssen’s literary source material is also noteworthy: for secular themes, for example, it is virtually confined to Ovid’s Metamorphoses. Other features of Janssen’s allegory are the lengthening of the figures’ lower limbs—which accentuates, instead of alleviating, the perspectival distortion due to the height at which the work would have been hung—and the superfluous drapery, which bears little relation to the figures beneath. All this is in contrast to Rubens’s balanced composition, which is perspectivally and anatomically correct. Janssen’s ponderous figures seem to be bowed under their own weight and that of their garments, a tendency taken to an extreme in the Nymphs Filling the Horn of Achelous (Seattle, WA, A. Mus.), a work that probably impressed the young Jacob Jordaens.

The contrast between Janssen’s sculptural ideal and Rubens’s artistic conception is well illustrated by their painted portraits for a series of Roman emperors. Janssen’s Nero (1618; Berlin, Jagdschloss Grunewald) emphatically recalls its stone prototype (e.g. Florence, Uffizi), a practice directly contrary to Rubens’s precept in his De imitatione statuarum. In his own Julius Caesar (1619; Berlin, Jagdschloss Grunewald), Rubens brilliantly demonstrated his idea of how the sculptural heritage of antiquity should be transformed on canvas into creatures of flesh and blood.

That Janssen was outclassed artistically by Rubens is not primarily to be explained by the opposition between the former’s retrospective classicism (Gerson and ter Kuile) and the dynamic novelty of the latter’s Baroque style. Janssen’s fundamental weakness is that he did not fully transpose his artistic sources, while the highly inventive Rubens was far more skilled in fusing the manifold borrowings into a new organic unity. Characteristically, Janssen achieved his best work when he could rely, for the composition as well as subject-matter, on a great predecessor. Another good example is Olympus, which probably represents Venus begging Jupiter to deify Aeneas from Ovid’s Metamorphoses (xiv, 585–603; see De Bosque) and forms a pendant to Venus Deifying Aeneas (both Munich, Alte Pin.). Here Janssen faithfully copied, in reverse, the composition designed by Raphael of Venus Begging Jupiter to Accept Psyche among the Gods frescoed on the vault of the loggia of the Villa Farnesina, Rome.

Janssen seems constantly to have drawn on the same limited sculptural repertory. The totally open, systematic way in which he borrowed from these sources and the conventional way in which he combined them set Janssen apart from his Netherlandish contemporaries. Highly characteristic is a combination such as in Lascivia (Brussels, Mus. A. Anc.): the composition is taken from a print by Hendrick Goltzius (b. 120) and the principal figure is derived from the antique statuary in the tradition of the Venus de’ Medici (Florence, Uffizi). The influence of the Bolognese school is evident in the triptych of the Coronation of the Virgin (Antwerp, St Jakobskerk). The Annunciation on the outer panels is taken, in reverse, from a print by Agostino Carracci (b. 7) or Pellegrino Tibaldi (b. 8), and the figure of Christ on the central panel is a literal borrowing from Annibale Carracci’s Coronation of the Virgin (New York, Met.), formerly in the Villa Aldobrandini, Rome. The Raising of the Brazen Serpent (c. 1605–6; Vienna, Pal. Schwarzenberg) strikingly resembles the work of the Dutch late Mannerists. Both in composition and in the handling of light, this work is at least as close to Cornelis Cornelisz. van Haarlem’s Death of the Children of Niobe (1591; Copenhagen, Stat. Mus. Kst)—for example in the contoured shadows on the bodies—as to the works of Caravaggio with which it is usually compared. The influence of Caravaggio is usually secondary in Janssen’s work, subordinate to the accentuation of his own sculptural ideal (see Müller Hofstede). Moreover, paintings of an indisputably Caravaggesque character, for example Philemon and Baucis (Wellesley Coll., MA, Mus.), are later in style than the Vienna painting, and it is even possible that Rubens played the part of an intermediary in passing on the Caravaggesque heritage.

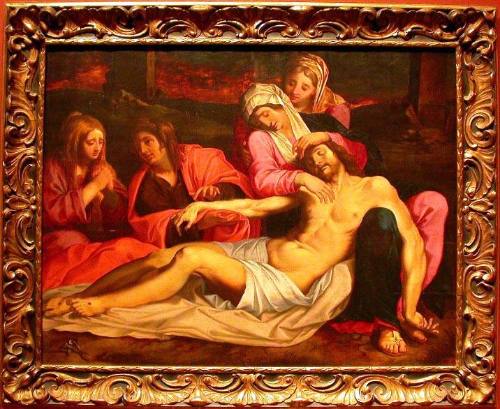

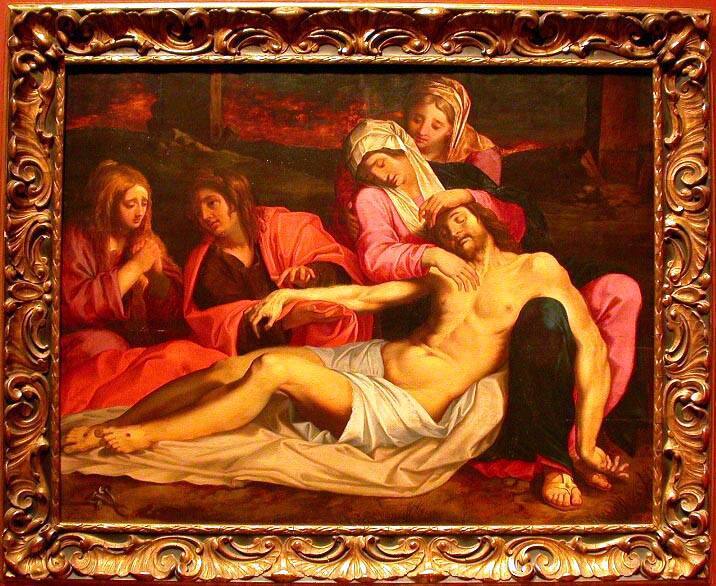

There were two genres in which Janssen made a lasting personal contribution to the art of his time: allegorical scenes with a limited number of figures in close-up, for example Gaiety and Melancholy (versions, Valencia, Lassala priv. col., and Dijon, Mus. Magnin), and contemplative scenes of the Passion, in which the meekly suffering Christ, as an object of devotion, appears almost palpably to intrude into the space of the spectator. In at least one case, the Lamentation (Mechelen, St Janskerk), the painting hung in a place dedicated to the Eucharist, so that the body of Christ was present to the praying faithful. From the 1620s, while Janssen continued to be successful with paintings of this kind, Rubens, with his monumental and dynamic ensembles for foreign courts, was supplying a market to which Janssen had no access. Janssen’s patronage was not confined to the cheap Spanish market, however, which he was able to reach more easily through his nephew Chrisostomus van Immerseel; he also executed more expensive commissions, both religious and secular, for local notables. The Virgo inter Virgines (after 1627; Lyon Cathedral), originally for the altar foundation and tomb of Jan Rogiersz. della Faille in the church of the Calced Carmelites in Antwerp, is an imposing example of Janssen’s mature style, although it owes much to Rubens. In the 18th century it was still regarded as one of the finest paintings in Antwerp. Not long afterwards, however, Janssen’s art was almost completely forgotten.

2. Working methods and technique.

Janssen’s extant oeuvre is relatively small, due not only perhaps to the assaults of time but also to his slow working method, which can be detected in most of the paintings. Moreover, most of the surviving paintings are damaged, due to frequent cleaning and possibly to the vulnerability of the thinly applied paint. Some of the paintings are horizontal in format, with nearly life-size figures. In the case of secular works, at least, this may be attributed to their function as overmantels. There are, however, also many paintings, both secular and religious, that are vertical in format, measuring c. 1.2–1.5×0.8–1.0 m; these were probably intended for private patrons.

Janssen’s works are difficult to date, chiefly because he often repeated motifs: technical or formal nuances in their elaboration, while important, are not a very precise indication of chronology. Typical of the entire oeuvre is the bole-coloured priming, reminiscent of Italian works, which gives the paintings a warm tonality, although the original effect would not have been as expressive as it has become with the increased transparency of the top layers of paint. This is evident, for example, in the outer garment of the figure of Patience in the otherwise well-preserved allegory of Man Succumbing to the Burden of Time, but Assisted by Hope and Patience (1609; Brussels, Mus. A. Anc.). In that work it is clear that after c. 1609 Janssen’s figures are no longer as rigid as they were previously, while the coloration is not yet dominated by tones of red, blue and yellow as it was after c. 1614, as can be seen, for example, in the addition of the large yellow and blue areas in the clothing of the figure on the extreme left of Peace and Plenty Binding the Arrows of War. Unlike the red and white of the other principal figures, these primary colours are not based on Ripa’s recommendations; they may instead have been influenced by Rubens, who seems just then to have been inspired by the theory of primary colours of the Jesuit Aquilonius. Also from this time onwards the still-life elements clearly show the influence of Frans Snyders, not surprisingly, as the latter collaborated with Janssen, for example in Meleager and Atalanta (Berlin, Kaiser-Friedrich Mus., destr.) and perhaps also to an extent in Sleeping Nymphs Spied on by Satyrs (Kassel, Schloss Wilhelmshöhe).

The flesh tones, which, especially in Janssen’s male figures, initially display an ochreous tint, become gradually paler and even chalk-like. From the mid-1620s the sculptural modelling of the figures becomes looser, as in the Scourging of Christ (1626; Ghent, St Michielskerk), while the atmosphere becomes elegiac, as in Christ in the House of Martha and Mary (Antwerp, St Pauluskerk) or in the later Virgin and Child with St John (Ponce, Mus. A.). The landscape in both works was painted by Jan Wildens; Janssen himself was not a skilled landscape painter, as revealed by his Meleager and Atalanta (Le Havre, Mus. B.-A.). There is also documentary evidence that Janssen collaborated with Jan Breughel II and Adriaen van Utrecht.

A large number of contemporaneous copies exist of several of Janssen’s paintings (for illustration see Jode, (3)), some of excellent quality, suggesting the existence of a busy workshop. None of Janssen’s known pupils, however, achieved any celebrity.

Joost Vander Auwera. "Janssen, Abraham." In Grove Art Online. Oxford Art Online, http://www.oxfordartonline.com.proxy.lib.fsu.edu/subscriber/article/grove/art/T043403 (accessed March 7, 2012).

Person TypeIndividual

Italian, c. 1610 - 1665