Roman Vishniac

American, born Russian, 1897 - 1990

Personal experience, culture, family and ethnic traditions, even a particular mother tongue--all of these factors constitute the connecting tissue of the personality of an individual. In the artist in particular these ``biographical'' characteristics have a deep influence on the individual's chosen mode of expression. And certain choices, apparently casual, can lead to the discovery of working tools, lifelong passions. In photography there seems to be almost an infinity of examples--from Lartigue to Bill Brandt to Aaron Siskind, all of whom became photographers because they found themselves with a camera in their hands by chance, and chance resolved an inward questioning. And so it was with Roman Vishniac, who was given a camera and a microscope when he was only six; he was already intensely curious about nature.

That trivial episode--long ago in 1904--was the first step to a destiny: science and photography have been interwoven throughout the whole of Vishniac's life. He is one of the great humanists of our time, a man in the tradition of the Italian Renaissance, when the figure of the scientist-artist was the key to the thought of the epoch that opened the door to the modern world. Science and art, then, were not in conflict--and neither are they in conflict for Vishniac: a simultaneity of expression of pure reason and abstraction is a reflection of the sublime expression of nature itself. A rare exponent of the new humanism, Vishniac has replaced empirical research with the modern tools of technology and the brush with the camera. Vishniac has a particular love for natural history, from the microscopic world of the life of insects to the world of the life of man. Patience, scrupulous reasoning, strict documentation, organized reasearch--he applies all of these gifts to the magic instrument of photography which he uses for the recording of truth.

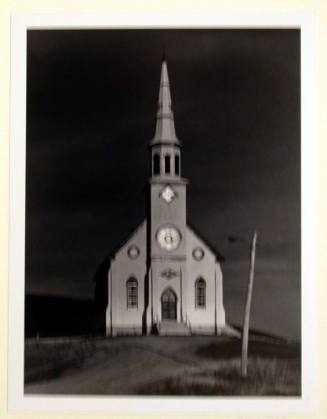

Internationally recognized for this work, for his outstanding research and photographic records, Vishniac entered the world of creative photography with a remarkable historical account of the Jewish communities of Eastern Europe, communities that were later completely wiped out by the methodical barbarity of the Nazis. In fact, this step involved no break in Vishniac's photographic methods: his scientific records and his human records spring from the same philosophy of life, a regard for every organism as an essential and irreplaceable part of the harmony of the universe. There is nothing casual about Vishniac. In four years, starting in 1936, he made a series of journeys to the eastern European ghettos, journeys that covered 5,000 miles, to record a world that he knew would disappear: ``And I thought maybe years and years after the killing, maybe the Jews will be interested to hear of the life that disappeared, of the life that is no more, and I went from country to country, from town to village.... It was a terrible task; I was many times in prison, but I returned again and again because I wanted to save the faces.'' He thus preserved the memory of what could no longer exist. Urged on by a conscious foresight based on a knowledge and analysis of past history, he responded to an inward necessity in himself which, as an individual belonging to an ethnic group, he transformed into the necessity of an entire community.

What is so extraordinary about Vishniac's account (apart from its enormous historical value) is the way in which he has made visual records as if in a sketchbook, a series of minute observations of customs that enables him to reconstruct the everyday history of a people. Accustomed to move about in the world of nature as if he were invisible, so as to leave its life undisturbed, he now moved unseen among people recording their attitudes, expressions, movements. In order not to interfere with their everyday activities he kept his camera concealed, operating it with his delicate hands by loving instinct. He became an integrated member of the community. His pictures record life as it was and, even though 40 years have passed, have the life and spontaneous freshness of pictures made today. Vishniac's transcends the limitations he imposed on himself: we are no longer looking at a historical record--``The life that disappeared; the vanished world of the Shtetl''--but at memory, which art can make eternal.

Every picture has a quality so tangible that we can feel the piercing cold in our bones and ourselves experience the worry that wrinkles the face of a woman, the disappointment of an unhappy little girl, the thoughtful wisdom of a studious old man, the shy smile of a youth setting out on a life that will never be--the fear, the desperation of not understanding the reason for the cruelty. And over it all, the song of prayer.... The testament of Vishniac is the visual counterpart of the tradition of mystically inspired Jewish culture, a historical cycle that ends in tragedy. The tales of Sholem Aleichem, the stories of Isaac Bashevis Singer, the philosophy and teaching of Hassidism collected by Martin Buber: these tell of men and places, of conditions and customs, of beliefs and sentiments--a whole world wiped out that can never be rebuilt. Vishniac grasps this world in its last moments, photographs it, fixes it forever. It is a heritage for everyone in the world who, through his work, may know that which they were never able to see.

Vishniac's words, ``Nature, God, or whatever you want to call the creator of the universe comes through the microscope clearly and strongly. Everything made by human hands looks terrible under magnification--crude, rough and unsymmetrical. But in nature every bit of life is lovely''--these words reveal the man to us, Vishniac the scientist and artist, and the profound value of his work.

"Roman Vishniac." Contemporary Photographers. Gale, 1996. Gale Biography In Context. Web. 21 Feb. 2012.

http://ic.galegroup.com.proxy.lib.fsu.edu/ic/bic1/ReferenceDetailsPage/ReferenceDetailsWindow?displayGroupName=Reference&disableHighlighting=false&prodId=BIC1&action=e&windowstate=normal&catId=&documentId=GALE%7CK1653000683&mode=view&userGroupName=tall85761&jsid=318ac8c372f1b9f4b13bca06d4c68ed5

Person TypeIndividual