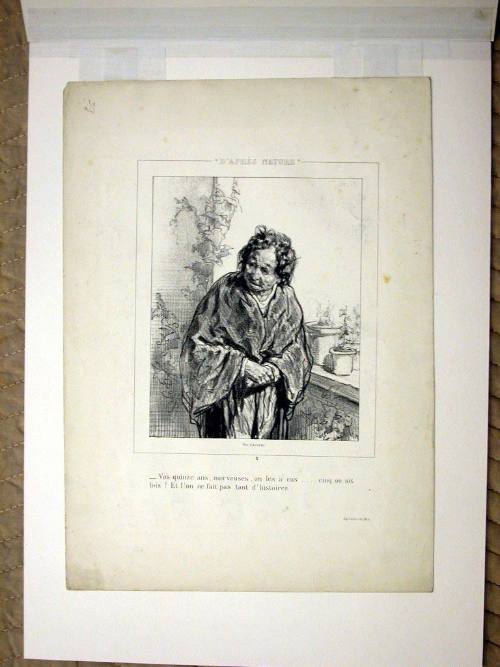

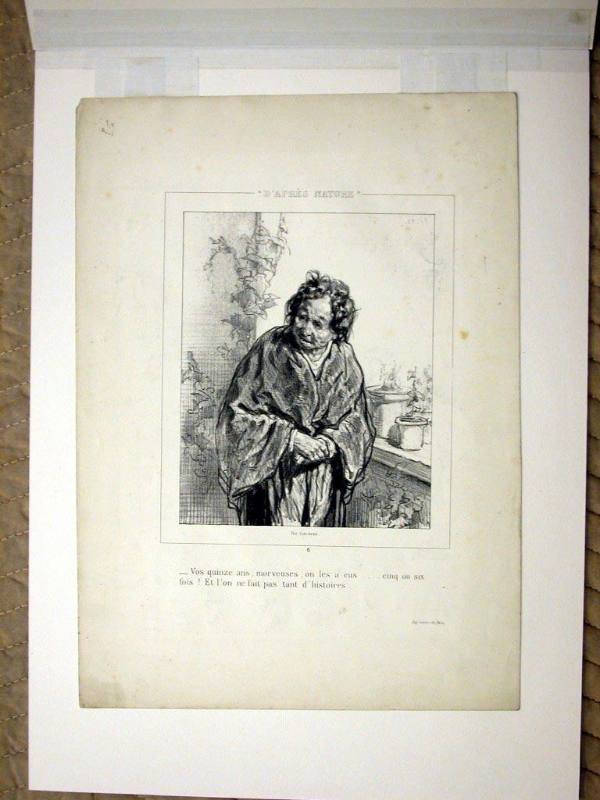

Paul Gavarni

French, 1804 - 1866

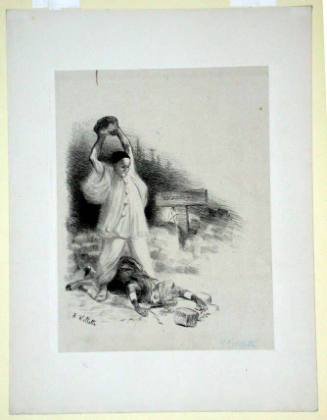

French lithographer and painter. He was one of the most highly esteemed artists of the 19th century. Like Daumier, with whom he is often compared, he produced around 4000 lithographs for satirical journals and fashion magazines, but while Daumier concentrated on giving a panoramic view of public life, it was said of Gavarni that his work constituted the ‘memoirs of the private life of the 19th century’. He specialized in genre scenes, in which the protagonists are usually young women, treating them as little dramatic episodes drawn from the light-hearted life of bohemia, dear to the Romantics.

Gavarni was initiated into the art of precision drawing while still very young, being apprenticed to an architect and then to a firm making optical instruments. He was also a pupil at the Conservatoire des Arts et Métiers. His first lithograph appeared when he was 20: a miscellany that accorded well with the taste of the time. His second work, the album Etrennes de 1825: Récréations diabolico-fantasmagoriques, also dealt with a subject then in fashion, diabolism. The pattern was set: all his life Gavarni produced works that would have been considered superficial if the delicacy of his line, his beautiful light effects and the wit of the captions he himself composed had not gained him admirers who found his prints both popular in their appeal and elegant. Gavarni also enjoyed writing, producing several plays now forgotten.

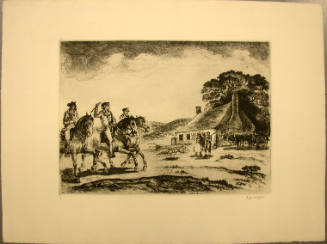

Nargeot (after Paul Gavarni): Muslin dresses designed by Mme Palmire,…From 1824 to 1828 Gavarni stayed in Tarbes in the Pyrénées, where he worked for a geometrician; but he constantly made drawings, especially of local costumes, which he later published in Paris. On this trip he acquired his pseudonym, the ‘cirque de Gavarnie’. Back in Paris he had his first taste of success with his contributions to fashion magazines. He was himself extremely elegant and sophisticated, and he adored women. He personified the dandy figure sought out by the Romantics and expressed his personal tastes in his drawings. In March 1831 Balzac introduced him to the paper La Caricature, owned by the Republican Charles Philipon, where he joined a team of young graphic artists, most notably Daumier, Jean-Jacques Grandville and Joseph Traviès, who were to raise the status of satirical lithography to new heights. Like them, he produced a few political caricatures directed against Charles X prior to the 1830 Revolution and a few satires against the monarchy in 1832, but he made a speciality of ball and carnival scenes, portraits of actresses and prints of costumes and fancy dress (see fig.).

In 1833, encouraged by the speed of his success, Gavarni founded his own magazine, Le Journal des gens du monde, where, surrounded by artist and writer friends, including Nicolas-Toussaint Charlet, Achille Devéria, Théophile Gautier and Alexandre Dumas, he combined the roles of editor-in-chief, graphic designer and journalist. The magazine was a commercial failure and closed after seven months and eighteen issues. From 1834 he began working on Philipon’s principal satirical journal, Le Charivari, and after 1837 became a regular contributor both to this and to L’Artiste, which since 1831 had been reporting on the art world. It was for Le Charivari that he made his main series of lithographs: The Letter-box, Husbands Avenged, Students, Clichy (1840–41) (the Parisian debtors’ prison to which he had been sent in 1835), The Duplicity of Women in Matters of the Heart (1840) and The Life of a Young Man (1841). In 1841–3 he made the ‘Lorettes’ famous: they were young women of easy virtue who haunted the new district around Notre-Dame-de-Lorette in Paris, to which businessmen and numerous intellectuals had been moving.

From the very start of his career in 1829, Gavarni’s prints had been published by Tilt in England, where they had been fairly successful. He stayed in England in 1847 and 1851, discovering the wretchedness of the working-class districts of London. There he published his Gavarni in London (1849). He began drawing in quite a different way, with greater social commitment and greater bitterness. It was also at this time, no doubt largely under English influence, that he worked in watercolour. On his return to France he published in Le Paris the long suite Masques et visages over the course of a year and at the rate of a lithograph a day (1852–3). The suite included several series: The English at Home, A Tale of Politicking, The Sharers, Lorettes Grown Old and Thomas Vireloque. This is perhaps his most important achievement. In it his graphic work is seen at its most lively. His line has become more tense and vigorous, the sense of contrast and movement greater, and the theme (the contrast between appearance and reality) more serious. He became moralistic and critical, often acrimoniously so, and his later work was not a popular success. The image created in the 1830s of a cheerful bohemia in which the lower orders of the bourgeoisie still mingled with the people had disappeared before the confrontation of the working class with the nouveaux riches. Gavarni superimposed on his habitual themes a profound disenchantment that owed much to his own aging, in such images as The Emotionally Sick (1853). He became increasingly reclusive, abandoning lithography in 1859 to concentrate on his garden, only to see it destroyed by the encroachment of the railways.

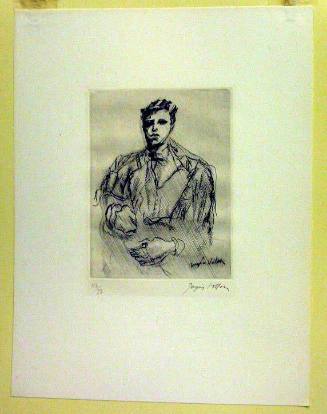

Gavarni was praised by the critics of his time: Balzac, Gautier, Sainte-Beuve and Jules Janin. Edmond and Jules de Goncourt, who befriended him after 1851, and of whom he made a lithograph portrait (for illustration see Goncourt, de), helped to sustain his reputation after his death. They contrasted the elegance of Gavarni’s themes favourably with what they considered the triviality of Daumier. This contrast obscured the more fundamental political division implicit in their work between a bourgeoisie faithful to its popular origins and one proud of its rise. For the latter Gavarni was a less dangerous artist than Daumier, although for later generations he appears less representative of the broad popular current that swept across France in the 19th century.

Michel Melot. " Gavarni, Paul." In Grove Art Online. Oxford Art Online, http://www.oxfordartonline.com.proxy.lib.fsu.edu/subscriber/article/grove/art/T031076 (accessed March 8, 2012).

Person TypeIndividual

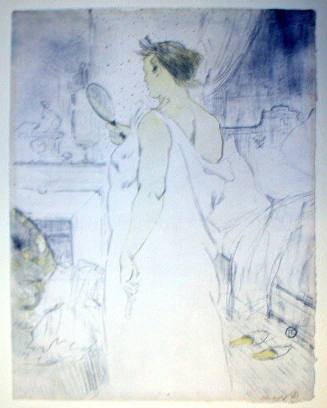

French, 1824 - 1898

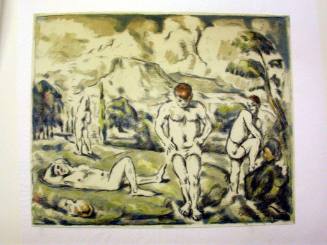

French, 1864 - 1901