Odilon Redon

French, 1840 - 1916

French printmaker, draughtsman and painter. He spent his childhood at Peyrelebade, his father’s estate in the Médoc. Peyrelebade became a basic source of inspiration for all his art, providing him with both subjects from nature and a stimulus for his fantasies, and Redon returned there constantly until its enforced sale in 1897. He received his education in Bordeaux from 1851, rapidly showing talent in many art forms: he studied drawing with Stanislas Gorin (?1824–?1874) from 1855; in 1857 he attempted unsuccessfully to become an architect; and he also became an accomplished violinist. He developed a keen interest in contemporary literature, partly through the influence of Armand Clavaud, a botanist and thinker who became his friend and intellectual mentor.

Redon’s vocation was still undecided in 1864 when he studied painting briefly and disastrously at the studio of Jean-Léon Gérôme in Paris. He returned to Bordeaux, and his commitment to the visual arts was strengthened by his friendship with Rodolphe Bresdin, whose drawings and prints he much admired. He learnt from Bresdin’s skills as an engraver and made etchings under his guidance. In 1868 and 1869 Redon published his first writings: a review of the 1868 Paris Salon and an article on Bresdin, both in the Bordeaux newspaper La Gironde. His criticism looked back to the provincial artistic values of his background but also forward to an art of the future that would advocate imagination rather than pursuing realism. Such views reflected his wider loyalties: to Rembrandt and Corot, and especially to Delacroix. These early developments matured into an active artistic career only after the Franco-Prussian War, in which Redon served as a soldier. He regarded this experience as the catalyst that finally produced in him a firm sense of vocation. He settled in Paris for the first time, spending only his summers at Peyrelebade, and he began to participate in Parisian artistic and intellectual life. He was by then producing large numbers of highly original charcoal drawings, which he called his Noirs (see fig.). They evoke a mysterious world of subjective, often melancholic fantasy. In 1879, partly at the suggestion of Fantin-Latour, he published his first album of lithographs, Dans le rêve.

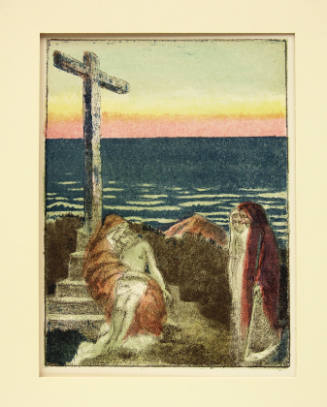

Lithographs formed a major part of Redon’s production during the 1880s and 1890s: he used them partly as a way of making his Noirs known to a wider audience, bringing to them textures as rich as his charcoal drawings. But he also developed the potential for links with the written word in titles and captions, for example The Marsh Flower, a Sad and Human Head (1885), whose caption was particularly praised by Stéphane Mallarmé. Above all he displayed in his lithographs audacious imagery that made the visionary seem plausible. Between 1879 and 1899 he published 12 lithograph albums. Some have strong literary associations; Flaubert’s La Tentation de Saint Antoine (Paris, 1874) served as the basis for albums in 1888, 1889 and 1896. Such literature-related works are not illustrations but interpretations that are independent works of art. In addition to the albums, he made various single lithographs and also a number of drawings after Baudelaire’s Les Fleurs du mal, which were reproduced in an album (1890) by the method of engraving known as the Evely process.

Redon held his first Paris exhibitions at the time of the early lithograph albums, showing charcoal drawings at the review La Vie moderne (1881) and in the newspaper Le Gaulois (1882). In 1884 he helped to organize the first Salon des Indépendants and in 1886 exhibited both at the last Impressionist Exhibition and with Les Vingt in Brussels. Although his Noirs made little impact on the general public, they won acclaim in the Parisian literary avant-garde. The aesthetic principles underlying Redon’s art were close to those of Baudelaire, as the Decadents, Baudelaire’s followers of the early 1880s, recognized. Emile Hennequin and Joris-Karl Huysmans became his champions; the Noirs figured in Huysmans’s Decadent novel A rebours (Paris, 1884). When the term ‘Symbolist’ became current as a description of the new art and literature in 1886, Redon was considered the major Symbolist artist. His works were widely debated in Symbolist reviews in Belgium as well as France, but Redon himself was alarmed at the excesses of many of these interpretations and maintained a discreet distance from such groups. His chief literary ally was Mallarmé, whom he met in 1883. Their friendship was close, although their only attempt at collaboration, Redon’s lithographs (1898) for Mallarmé’s Un Coup de dés, was not completed. Redon has been termed ‘the Mallarmé of painting’.

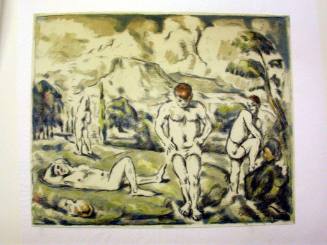

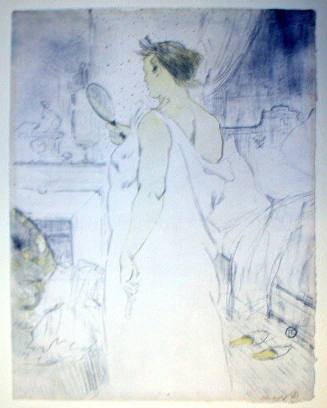

Redon’s reputation until 1890 rested entirely on work in black and white, but he had been using colour in unexhibited landscape studies. From about 1890 he began to extend his use of colour to works that repeat or develop the subject-matter of the Noirs. Many of these were oils, such as Closed Eyes (1890; Paris, Mus. d’Orsay), but pastels also became frequent (e.g. Christ in Silence, c. 1895; Paris, Petit Pal.). During the 1890s he used colour alongside monochrome, colour gradually becoming dominant, and after 1900 he abandoned the Noirs. Earlier subject-matter recurred, but new motifs also appeared, flowers, especially, becoming a central preoccupation (see fig.). The increasingly decorative tone of these works led to commissions for screens and murals, an outstanding example being the paintings (1910–11) on the walls of the library at Fontfroide Abbey near Narbonne. The serene lyricism of these late colour works contrasts with the prevailing melancholy of the Noirs, but Redon’s fundamental aesthetic had not altered. The transformation of nature into dream-like images, suggesting indefinite states of mind and expressed in sumptuous textures, remained his central concern, and the exploratory freedom with which he investigated the suggestive potential of colour contributed considerably to Post-Impressionist art. His innovations were admired by the Nabis and by some of the Fauves, including Matisse.

In 1899 Paul Durand-Ruel exhibited Redon’s works with those of the Nabis, thereby paying homage to his importance to young painters such as Bonnard and Vuillard. A large selection of his works was shown at the 1904 Salon d’Automne, contributing to the advent of Fauvism. New generations of writers, including Gide and Cocteau, became his companions and interpreters. His reputation spread abroad, notably at the American Armory Show of 1913. Redon’s work did not, however, become popular with the public, and he depended heavily in his later years on individual patrons and collectors, such as André Bonger (1861–1934) in the Netherlands, Gabriel Frizeau (1870–1938) in Bordeaux and Gustave Fayet (1865–1925) at Fontfroide.

Redon had married in 1880, but his first son, Jean, died in infancy in 1886. Only later in his life did domestic happiness accompany his increased prestige. His second son Arï (1889–1972) stimulated the joy and optimism of the late colour works and became a patient advocate of his father’s art. His collection of Redon’s works, including hundreds of drawings, is now owned by the Musée d’Orsay, Paris, although much of it is currently displayed in the Louvre. After Redon’s death, his family and friends completed a project that he had instigated: the publication of selections from his writings under the title A soi-même (1922). It contains autobiography, diaries, art criticism and general reflections, and demonstrates Redon’s considerable skills as a writer as well as providing valuable insights into his work.

Richard Hobbs. "Redon, Odilon." In Grove Art Online. Oxford Art Online, http://www.oxfordartonline.com.proxy.lib.fsu.edu/subscriber/article/grove/art/T071074 (accessed March 7, 2012).

Person TypeIndividual

French, 1824 - 1898

French, 1864 - 1901