Antonio Tapies

Spanish, 1923-2012

In the words of Jean-Luc Chalumeau, Tàpies's early paintings, shown in Paris in 1957 at the Galerie Stadler, were 'elegant signs inscribed in a thick, sandy pigment'. By 1945 he had produced a good number of works, the technique of which clearly foreshadowed the future development of his art with the thick, coarse use of pigment, made of earth and various other ingredients, of scraps, and sometimes incised with graffiti suggesting the form of heads. Tàpies started engraving in 1949; at this time, having abandoned the intuitive approach of his early pieces, his work shows a clear Surrealist influence. From 1949 to 1951 he painted figures, animals, objects and landscapes in an entirely dreamlike atmosphere, the forms merging through effects of transparency with blurred haloes of light and superimposed gradations of bright colours, creating a poetic imagery which reveals Klee's influence.

In 1952 Tàpies's work took a new, more geometric direction; however, in 1953 he returned to the thickly-applied impasto and collage effects of his early work. According to J.E. Cirlot, one of his principal biographers, Tàpies had developed and extended his use of pigment: 'At the end of 1953, he simplified forms to an extraordinary degree, while at the same time emphasising in the construction of his image the use of a blend of oil, powder and marble. Early in 1954 he replaced oils with latex paint, which he used to draw large, abstract signs on to the relief of his thick impasto... his creative approach became increasingly simplified, monumental and hermetic'. In 1957 the nature of his concept and technique were confirmed in the increased simplicity of his visual field, the almost uniform use of pigment, broken only by a single deep groove revealing its true nature, as if to dispel any illusions of a possible similarity with old walls or worm-eaten old wood. In 1958, he produced his first lithographs and in September 1962 a large mural at the library of the University of St Gall in Switzerland. In 1967 Tàpies held a solo exhibition in Paris in which, discreetly and almost humorously, elements of reality began to appear in his paintings, as in Matter Folded in the Form of a Walnut (Matière Plissée en Forme de Noix), Matter in the Form of a Foot (Matière en Forme de Pied) and Three Chairs (Trois Chaises); reality emerges again in the form of impressions of spectacles, a hat, or nudes, perhaps in a muted echo of the eruption of the real in Pop Art and in the work of the French New Realists.

After these exhibitions, from 1969, he began to incorporate more modest materials into his work such as crumpled newspaper, old bags, old blankets and bundles of straw. Many critics, and his biographer Alexandre Cirici in particular, see the artist as a forerunner of arte povera because he 'was the first to understand, with a very special sense of history, the grandeur of humble things, the fact that the image of poverty can reflect what is least alienated about man'. However, Tàpies requires no such accolades. His work stands alone, solidly anchored in informal abstraction, a forerunner of the importance of the tactile appearance of the pigment itself. It is significant in its apprehension of the monochrome, in the development of 'field painting', related to the 'Zen' approach of the Pacific School and to Minimal Art. Daniel Abadie, who has written extensively about Tàpies, describes his paintings as having "the emotional richness we sometimes glimpse in a footprint on a beach washed by the sea, in the insolent or livid streak slashed across on an old plaster wall, in the slow erosion of stones'.

By contrast, his 'poor' paintings of the 1970s like Large Bundle of Straw and Piled-up Newspapers reveal a different side to his work. The critic Michel Conil Lacoste gives an interesting analysis of Tàpies's work at this period, commenting that, while his style remains faithful to his speciality, the seduction of the unpolished, 'his situation was highly typical of at that time. He was like an artist who, having outstripped others with his purely aesthetic radicalism (not forgetting the psycho-metaphysical implications) but still within a specific economic circuit, now finds himself outmoded or even overburdened by a global questioning that leaves him behind, without warning, on the very path where he had been the pioneering force'.

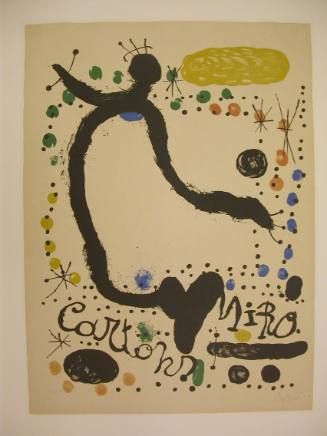

In the 1980s, Tàpies began to favour a new material, varnish, which he began to use as a base and binder for his paintings (particularly with marble powder) and as a colour. He used it on cardboard and paper, taking advantage of its fluid and transparent texture in works of great restraint that Jacques Dupin has compared with Chinese washes. These light, ethereal works appear to mark a complete break with the rich, thickly-applied and incised pigment of his earlier works. At the same time, in another series, he continued to work in relief, airbrushing paint on to fine, moistened canvases placed over a body or object. From 1970 onwards he produced a large number of sculptures, in particular assemblages created from everyday objects such as chairs, a stack of plates or a large, knotted denim sheet. He received a public commission to produce a monument to Picasso in Barcelona, which was inaugurated in 1983; the piece consists of a plastic cube containing the furniture of a typical middle-class Catalan family home, crossed by steel bars and tied round with sheets on which Picasso's words are inscribed in red lettering: 'No, painting is not done to decorate apartments, it's an offensive and defensive weapon against the enemy'. From 1981 he worked in Hans Spinner's studio, producing pieces in fire-clay such as Skull (1988) and Foot (1991). Modelled, sculpted, incised and coated in black enamel, these sculptures remind us of primitive forms marked by the passing of time.

Tàpies's work displays recurring images such as crosses (which he adopted as the initial letter of his surname), letters and words, figures, graffiti and imprints, particularly of feet and shoes. These images place his work in a primitive world, inhabited by signs, where figurative and abstract co-exist. He works on surfaces that evoke ancient, crumbling walls, eaten away by time, in rough, cindered earth and in a reduced range of tones, from black to ochre, from brown to grey, with an occasional flash of highly symbolic red. He tirelessly explores materials such as sand, marble powder and dust, seeking a texture which, in his own words, is capable of 'presenting a cosmic theme of meditation and reflection on the beauty of infinite combinations of the forms, colours and materials of nature'.

In 1948, Tàpies exhibited for the first time at the October Salon in Barcelona. He has since taken part in numerous collective exhibitions, including: Carnegie Foundation International Exhibition, Pittsburgh (1950 and 1952); Venice Biennale(1952, 1954 and 1958); São Paulo Biennale (1954 obtaining the Young Painters' prize and 1957); Carnegie International Exhibition, Pittsburgh (1954 and 1967); Phases exhibition in Paris organised by Édouard Jaguer and 3rd Hispano-American Biennale, Barcelona, where he was awarded the Republic of Colombia prize (1955); Tate Gallery, London (1962); Guggenheim Museum, New York, where he was awarded a prize by the Guggenheim Foundation and Documenta III, Kassel, where an entire room was devoted to his work (1964); Ljubljana Engraving Biennale (1967); 85 Artists in Search of a Viewer, Colegio de Arquitectos, Barcelona (1969); Nouvelle Biennale, Paris (1985); Eduardo Chillida - Antoni Tàpies, Deutsche Guggenheim, Berlin and Le Corps à corps dans la peinture d'Antoni Tàpies, Musée Picasso, Antibes (2002); Painting in Three Dimensions (Peindre en Trois Dimensions), Musée Ingres, Montauban (2003).

He has also shown his work in numerous solo exhibitions, including: Institut Français, Barcelona (1949); municipal museum, Mataró (1953); Martha Jackson Gallery, New York (regularly from 1953); Sala Gaspar, Barcelona (regularly from 1955); Galerie Stadler, Paris (1956 his first solo exhibition followed by numerous others, particularly from 1967 at the Galerie Maeght); Museo de Arte, Bilbao (1960); Di Tella Institute national museum, Buenos Aires (1961); fine arts museum, Caracas, Kestner-Gesellschaft, Hanover and Guggenheim Museum, New York (1962); Institute of Contemporary Art, London (1965); Kunstmuseum, St Gall (1967); Museum des 20 Jahrhunderts, Vienna and the Kunstverein, Hamburg (1968); Musée d'Art Moderne, Paris - a first retrospective exhibition in France (1973); Hayward Gallery, London (1974); Maeght Foundation at St-Paul-de-Vence and Miró Foundation, Barcelona (1976); Albright-Knox Art Gallery, Buffalo (1977); Kiel Kunsthalle (1980); museum of contemporary art in Madrid - a first retrospective in Spain - and Stedelijk Museum, Amsterdam (1980); fine arts museum, Mexico City (1981); the Abbaye de Sénanque, Gordes (1983); Palazzo Reale, Milan (1985); Künstlerhaus, Vienna and Van Abbemuseum, Eindhoven (1986); Tàpies by Tàpies, Cantini Museum, Marseilles and the Kunstsammlung Nordrhein-Westfallen, Düsseldorf (1989); Centro de Arte Reina Sofia, Madrid (1990); Museum of Modern Art, New York and Serpentine Gallery, London (1992); Lund Kunsthalle, Prins Eugens Waldermarsudde museum, Stockholm and Galerie Nationale du Jeu de Paume, Paris (1994); Paper Spirit (Esprit de Papier) at the Galerie Daniel Lelong, Paris (1998); Antoni Tàpies or the Poetics of Matter. Engravings and Books (Antoni Tàpies ou la Poétique de la Matière. Estampes et Livres.) Bibliothèque Nationale de France, Paris (2001); Tàpies, Escriptura Material. Llibres at the Antoni Tàpies Foundation, Barcelona (2002); Tàpies - New Paintings (Tàpies - Nouvelles Peintures), Galerie Lelong, Paris (2003).

He has won numerous awards including: Lissone prize (1957); Tokyo international engraving Biennale prize (1960); Ljubljana Biennale Grand Prix for the visual arts (1967); fine arts gold medal awarded by the King of Spain (1981); national Grand Prix for Painting in Paris(1984). In 1979 he was made a member of the Berlin academy; in 1981 doctor honoris causa of the Royal College of Art, Great Britain; in 1983, an Officer of the Order of Arts and Letters, Paris; in 1988, doctor honoris causa of the university of Barcelona and Commander of the Order of Arts and Letters and in 1989, a member of the Real Academia de Bellas Artes de San Fernando.

"TÀPIES, Antoni." In Benezit Dictionary of Artists. Oxford Art Online, http://www.oxfordartonline.com.proxy.lib.fsu.edu/subscriber/article/benezit/B00179580 (accessed April 16, 2012).

Person TypeIndividual