Image Not Available

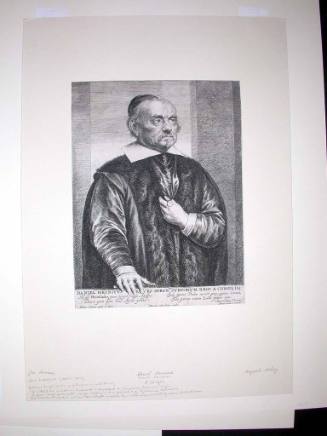

for Gérard de Lairesse

Gérard de Lairesse

Dutch, 1640 - 1711

Painter, draughtsman and printmaker from Liège. A contributor to the ‘gallicizing’ of Dutch art in the second half of the 17th century, he was a talented painter who served a wealthy, cultivated bourgeoisie for whom he painted complex allegories. He was not only a great painter but also a first-class draughtsman and engraver, and an influential theorist whose books reflect the proselytizing zeal of the late 17th-century promoters of classicism.

1. Life and artistic career.

He was the second son of the painter Renier de Lairesse (1597–1667), who probably also taught his son. Gérard de Lairesse’s early works, for example Orpheus in the Underworld (Liège, Mus. Ansembourg), the Conversion of St Augustine (Caen, Mus. B.-A.) and the Baptism of St Augustine (Mainz, Landesmus.), show the overpowering influence of Bertholet Flémal, then the dominant painter in Liège; great importance is given to Classical architectural settings and strong colour, while the works also show a distinct taste for gesture and a predilection for atmospheric lighting. During these early years Lairesse received numerous religious commissions, but in 1664 a love affair forced his sudden departure from Liège. He took refuge at ’s Hertogenbosch, then in Utrecht for several months, and in 1665 or 1666 he moved to Amsterdam, possibly persuaded by the picture dealer Gerrit van Uylenburg. His arrival in Amsterdam plunged him into an artistic, religious and social milieu very different from that of Liège, but he integrated very quickly into the life of the commercial centre.

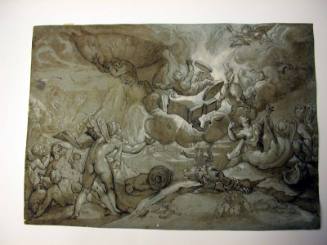

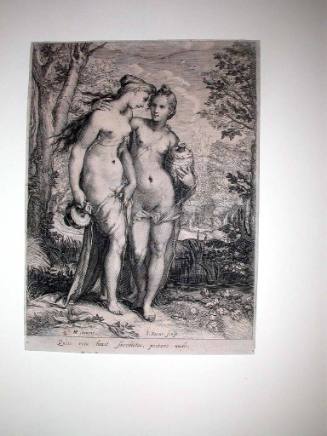

In 1667 Lairesse acquired citizenship and developed friendships with the city’s intellectual élite, who were greatly attracted by the brilliance of French civilization and art. They founded a society of artists, which was regularly attended by Lairesse, who was appointed their engraver and illustrated the plays of the society’s founder, Andries Pels (1631–81): the Death of Dido (Timmers, nos 61–4) and Julfus (1668; Timmers, nos 93–5). Lairesse rapidly became famous in Amsterdam both for the many pictures he executed for collectors and for the large numbers of plates he engraved. He rejected the naturalistic style of Dutch art and produced instead works of considerable theatricality, particularly of subjects from Ovid and Virgil (e.g. Venus Offering Arms to Aeneas, 1668; Antwerp, Mus. Mayer van den Bergh). In the early 1670s he produced works that were even more classical in character, with monumental figures evocative of ancient statues and an increasingly refined sense of composition. These paintings tended to be moralizing in subject-matter (e.g. Antiochus and Stratonica; Amsterdam, Rijksmus.).

Lairesse’s success as the ‘Dutch Poussin’ brought him to the attention of the city authorities. In 1667 he produced an elegant allegorical painting celebrating the Benefits of the Peace of Breda (The Hague, Gemeentemus.), and in 1674 he celebrated the military victories of William III, Stadholder and Prince of Orange-Nassau, in several large plates, including an Allegory of the Peace of Westminster (Timmers, no. 71). Lairesse was soon in demand for more ambitious commissions and undertook decorative schemes for patrician houses on the Herrengracht; many of these had complex allegorical ceilings extolling the virtues of their owners (e.g. the ceiling of the Leprozenhuis, c. 1675; Amsterdam, Hist. Mus.). Lairesse’s style became increasingly elegant, and he made greater use of light colours. Great attention was paid to the appearance of the work within the overall context of its setting. This pursuit of formal elegance is found in most works of this period, for example Amsterdam Receiving the Homage of the World (Amsterdam, Hist. Mus.).

At the same time Lairesse continued his printmaking activities, producing plates that display his extraordinary command of the technique of etching and into which he could sometimes channel his religious inspiration, little favoured by Dutch Protestantism (e.g. the Ecstasy of St Theresa, c. 1675; Timmers, no. 15). It was during this period that Lairesse produced his most popular works, including Achilles with the Daughters of Lycomedes (Brunswick, Herzog Anton Ulrich-Mus.) and the Death of Germanicus (Kassel, Schloss Wilhelmshöhe).

From 1680 Lairesse began to simplify his compositions, increasing their solemnity by isolating larger, weightier figures against architectural backgrounds. The colour became more subtle with an elaborate shot-silk effect (e.g. Hagar and the Angel; St Petersburg, Hermitage). New themes appeared, scenes of satyrs and maenads in unfettered bacchanals, combining unbridled paganism with a remarkable sense of classical reconstruction (e.g. Bacchanal, c. 1680; Kassel, Schloss Wilhelmshöhe). Another aspect of his decorative talent is seen in his series of grisailles painted for patrician houses in Amsterdam: he invented a new type of allegorical trompe l’oeil décor, exemplified by the Four Ages of Man (1682; Orléans, Mus. B.-A.). Lairesse was also involved in the decoration of William III’s castles at Soestdijk, for which he painted a Bacchus and Ariadne (c. 1682; The Hague, Mauritshuis), and at Het Loo (e.g. the ceiling of Queen Mary’s Bedroom, c. 1686; in situ). At the request of Archdeacon de Liverloo of Liège, Lairesse resumed his religious painting with a monumental Assumption (Liège Cathedral), painted in 1687 for the high altar of St Lambert’s Cathedral (destr. 1794); this painting shows the artist’s virtuoso treatment of traditional Christian iconography within a classical composition.

In 1684 the landscape artist johannes Glauber arrived in Amsterdam; he collaborated with Lairesse on several commissions and brought out an even greater emphasis on classicism in Lairesse’s later work. The most striking example of their collaboration is probably the decorations for a room in the home of the merchant Jacob de Flines (Amsterdam, Rijksmus.), in which the walls were hung with canvases featuring great Italianate landscapes populated in the foreground by half-length figures painted by Lairesse; they look directly at the viewer, thus linking the real and the fantasy worlds. Between 1685 and 1690 Lairesse’s activity was particularly varied and included the decoration of the new theatre of Amsterdam (destr. 18th century) and the decoration of the organ shutters (1686; in situ) in the Westerkerk, Amsterdam. His last great monumental work was a series of seven large canvases (c. 1688) for the Council Room of the Binnenhof in The Hague. Lairesse’s composition illustrates the Prince’s virtues (Justice, Prudence etc) with scenes from Roman history. The composition is rigorous, the architecture classical; the figures are vigorously modelled and give the impression of sculptures fixed in timeless gestures. The artist was preparing to participate in the decoration in the Burgerzaal of the new town hall in Amsterdam and had already executed the sketch for an Allegory of the Glory of Amsterdam (c. 1687; Amsterdam, Hist. Mus) when, in 1690, he was suddenly struck by blindness, putting a stop to a pictorial career as brilliant as it was fruitful.

2. Art theory.

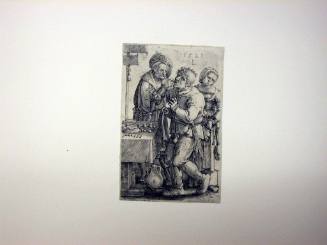

Deprived of his sight and thus of his livelihood, Lairesse spent the last ten years of his life giving art lectures, which seem to have been a great success. His sons brought out the first volume of these talks in 1701 under the title Grondlegginge der teekenkunst (‘Principles of design’), followed in 1707 by a much larger work entitled Het groot schilderboek (‘Great book of painters’). This subsequently went into many editions, both in Amsterdam and elsewhere in Europe, and played an important role in the origin of Neo-classical ideas. In the book Lairesse defended the most intransigent form of academicism, which in his eyes was embodied only by Poussin and Le Brun; Rubens and Rembrandt are hardly mentioned. He also strongly advocated the slavish copying of the Antique and nature because, according to him, ‘art proceeds from reason and judgement’. Lairesse had nothing but contempt for such minor realist painters as Adriaen van Ostade, Adriaen Brouwer or David Teniers the younger, all of whom he considered vulgar; the painter’s preference should be for historical, mythological or allegorical subjects, genres that could educate the mind and move the heart. A manual for artists rather than a proper treatise on painting, Het groot schilderboek is still an important work, as much for the information it provides on the artist himself (he sometimes referred to his own work) as for the knowledge it imparts of Dutch art in the second half of the 17th century.

3. Critical reception and posthumous reputation.

Regarded as a painter of the highest rank by his contemporaries, Lairesse continued to be admired and appreciated throughout the 18th century, when his pictures fetched high prices. He fell into scornful disfavour and was pronounced ‘superficial’ during the 19th century, a time when Realism made its appearance and when the Impressionist painters, who rejected all iconography, were violently opposed to academic art.

Alain Roy. "Lairesse, Gérard de." In Grove Art Online. Oxford Art Online, http://www.oxfordartonline.com.proxy.lib.fsu.edu/subscriber/article/grove/art/T048796 (accessed May 3, 2012).

Person TypeIndividual