Image Not Available

for Joseph Highmore

Joseph Highmore

English, 1692 - 1780

English painter and writer. The son of a coal merchant and the nephew of Thomas Highmore (1660–1720), Serjeant-Painter to the King, he was articled to an attorney on 18 July 1707. Bored with his duties, he attended Kneller’s Academy from 1713 and in 1715 abandoned law, setting up as a portrait painter in the City of London. From 1720 he attended the St Martin’s Lane Academy, where he was able to study contemporary French styles in art and design, particularly that of Gravelot. He read widely and mastered Brook Taylor’s system of perspective (1715). He also attended William Cheselden’s anatomy lectures and contributed designs to that author’s Anatomy of the Human Body (1722). In 1723 Highmore moved to Lincoln’s Inn Fields, which lay to the west of the City—a more convenient location for those who needed to find a market for their art. In 1725 he was employed by John Pine (1690–1756) to make 20 drawings for engravings of the recently revived order of the Knights of Bath; among these was his portrait of the Duke of Richmond (Goodwood House, W. Sussex). In 1732 he travelled to the Low Countries to study works by Rubens and van Dyck, and two years later he went to Paris, where he saw the art collections at Versailles and in the Palais du Luxembourg and the Louvre, as well as several important private ones. In the following years he secured commissions from the royal family, such as Queen Caroline of Ansbach (c. 1735; London, Hampton Court, Royal Col.); however, his patrons were more often middle-class sitters.

In 1739 Highmore presented his earlier portrait of Thomas Emerson (1731; London, Foundling Hosp.) to the Foundling Hospital upon Emerson’s assumption of its Governorship in that year. He also painted for the same institution a rare historical work, Hagar and Ishmael (1739; London, Foundling Hosp.), that suggests some uneasiness on his part with problems of space and depth.

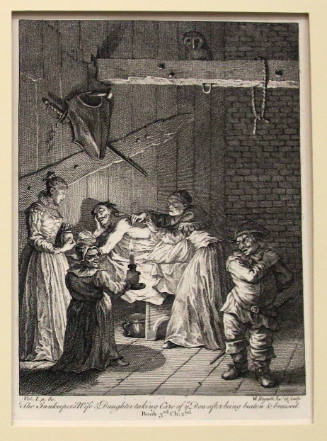

In the 1740s Highmore’s work was increasingly aimed at a middle-class clientele, his popularity with whom was in part due to his ability to capture a likeness in one sitting and to create an informal composition. This can be seen in his conversation pieces, such as that of Mr Oldham and his Guests (1740s; London, Tate), an unpretentious and unflattering depiction of a group of men seated around a table drinking and smoking. His portraits of An Unknown Man with a Musket (1745; Cambridge, Fitzwilliam) and Samuel Richardson (1747; replica London, N.P.G.) are further examples of the faithful likeness and unpretentious format sought by such sitters. Highmore’s series of 12 paintings from Pamela (1744; Cambridge, Fitzwilliam; Melbourne, N.G. Victoria; London, Tate) were designed especially to be engraved and to capitalize on the success of Richardson’s eponymous novel (1740–41). Although following the serial tradition of Hogarth’s Harlot’s Progress (?destr. 1755) and Marriage à la mode (London, N. G.), Highmore’s Pamela was illustrative rather than inventive, and compositionally simple, not crowded and complex. The depicted narrative was intended to be read at a glance rather than interpreted and considered in the way that Hogarth’s narratives were. Pamela and Mr B. in the Summer House (Cambridge, Fitzwilliam) is a typical example of how Highmore used an uncluttered interior setting and the minimum number of figures to make events in the novel immediately identifiable. The engravings of this series, by Antoine Benoist (1721–70) and L. Truchy (1731–64), published on 1 July 1745, enjoyed widespread and immediate popularity.

Highmore exhibited at the Society of Artists and Free Society in 1760 and 1761. He sold the contents of his studio in 1762 and retired to Canterbury with his daughter and son-in-law. In retirement he pursued a second career, that of a writer, which he had begun in 1754 with a critical examination of Rubens’s ceiling decorations in the Banqueting Hall, London. In articles written for the Gentleman’s Magazine Highmore further defended Rubens (1766) and examined colour theory (1778), postulating the idea that pure, unmixed colours would, from a distance, appear to blend. He also wrote a book on Brook Taylor’s theory of perspective (1763), and his collection of moral essays (1766) included a consideration of why artists were not the only proper judges of art. His son Anthony Highmore (d after 1780) was a landscape painter, whose works were occasionally engraved.

Shearer West. "Highmore, Joseph." In Grove Art Online. Oxford Art Online, http://www.oxfordartonline.com.proxy.lib.fsu.edu/subscriber/article/grove/art/T038069 (accessed May 2, 2012).

Person TypeIndividual