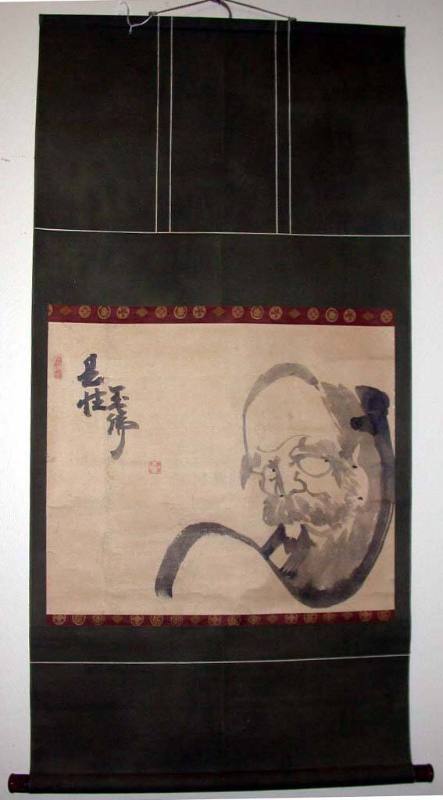

Hakuin Ekaku

Japanese, 1685 - 1786

Japanese Zen monk, painter and calligrapher. He was one of the most important painters of the Edo period (1600–1868), creating hundreds of paintings and calligraphies that revolutionized Zenga (painting and calligraphy by Zen monks from the 17th century to the 20th; see Japan, §§VI, 4(vii) and VII, 2(iv)). In earlier centuries, Zen painting and calligraphy had been generally limited to portrayals of famous masters of the past, landscapes and Zen phrases or poems. Under Hakuin’s influence, however, a new range of styles and of subjects—including Zen-related subjects, those drawn from other Buddhist sects and from native folklore—made Zenga appealing not only to the Zen initiates but also to lay people. In this way Hakuin responded to the Tokugawa government’s lack of support for Zen; he reached out to people of all beliefs and levels of education through art that had both humour and dramatic impact. Indeed, his use of art in the service of religion permanently changed the Zenga tradition.

1. Life.

Hakuin was the fifth child of a family of devout Buddhists. According to his own account, he was still a child when he heard a terrifying sermon on the Buddhist hells by the evangelistic Nichiren-sect monk Sho-nin ( fl c. late 17th century) and determined to become a monk himself. He began his Zen Buddhist studies at the age of 14 at the Rinzai-sect temple of Tokugenji in Hara, and later spent many years travelling to different Zen teachers (angya) for instruction. As a priest he took the name Ekaku.

In 1718 Hakuin settled at the small Rinzai temple of Sho-inji in Hara, declining positions in more famous monasteries to avoid the potential interference of government officials or wealthy patrons. He trained many pupils through strict methods that included ko-an (Zen conundrums that can be understood only through enlightened vision and after long meditation) taken from Chinese Zen records. He also wrote on various subjects, including writings and lectures on traditional Zen texts and a commentary on the popular Buddhist Heart su-tra, a part of the Daihannya haramittakyo- (Skt Maha-prajña-pa-ramita- su-tra; the greater su-tra of the Perfection of Wisdom), which he mischievously called a ‘useless collection of junk’.

Around the age of 60 Hakuin began to turn more often to brushwork to express his Zen vision. He had received some training in calligraphy, and perhaps in painting, in his youth, but had abandoned the attempt to become an artist. He discovered in his later years, however, that painting and calligraphy could convey more than words alone, and in his last 25 years he produced a large amount of Zenga. Although all of his known works bear his seals, most are unsigned and undated. However, his works are often divided, on stylistic criteria, into early (1745–55), middle (1755–65) and late (1765–9) periods.

2. Work.

(i) Early period, 1745–55.

Hakuin’s paintings from his 60s display a wide range of subject-matter, from traditional themes such as the first patriarch of Zen Buddhism, Bodhidharma (Jap. Daruma or Bodaidaruma) to entirely new subjects. An example of the latter is Blind Men Crossing the Bridge (priv. col.; see Addiss, pl. 55), in which tiny figures can be seen creeping and crawling over a log bridge spanning a chasm. The imagery of blind men crossing a bridge, as explained by the calligraphy on the piece, is a metaphor for a ‘mind that can cross over’, that is, an enlightened mind. The dominant ink tonality in such early works by Hakuin is usually grey, occasionally with added colours, and the calligraphic inscriptions are in vibrant but rather spidery script.

Another of Hakuin’s early subjects is the folk figure Otafuku, the low-ranking, aging courtesan who was the embodiment of the virtuous, hard-working woman. Hakuin depicted her variously as an elegantly dressed geisha, cooking rice cakes, or putting hot moxa on the rear end of a rich old customer with haemorrhoids (e.g. a hanging scroll, Tokyo, Eisei Bunko). In such paintings Hakuin suggests that compassion and service to others are more important than wealth or high position. Hakuin also depicted subjects and sayings from Confucianism, Shinto and the Esoteric and Pure Land Buddhist sects.

Another theme of his early period was the ebi (shrimp). With its bent back and long ‘whiskers’, the ebi was an appropriate if not classical symbol of old age. On some of Hakuin’s paintings of this subject, brushed for his monk followers, he wrote, ‘If you want to live a long life, moderate your eating and sleep alone’. He would not expect a farmer or shopkeeper to be celibate, so he painted other pictures of ebi with the inscription, ‘If you want to live a long life, moderate your eating, moderate your eating’.

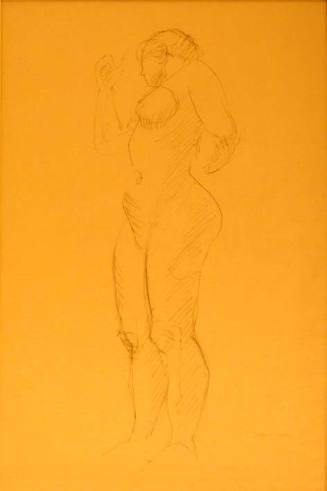

(ii) Middle and late periods, 1755–69.

In his 70s, his middle period, Hakuin continued his wide range of themes but began to use a thicker and heavier calligraphic line, bringing more sense of direct power to his works. He did several portrayals of Kannon (Skt Avalokiteshvara; Chin. Guanyin), the bodhisattva of mercy, sometimes adding conventional inscriptions about the compassion of Kannon. On other Kannon paintings, however, he introduced the surprising notion that the deity might be tired and overworked by people’s constant entreaties. This was Hakuin’s humorous way of attempting to make people think twice about their accepted beliefs.

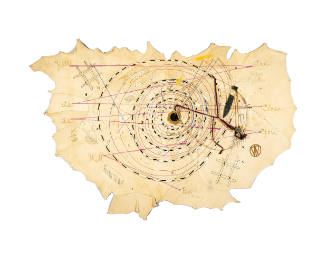

During this period Hakuin also depicted the rotund monk Hotei (Chin. Budai), one of the seven Gods of Good Fortune, who preferred a life of wandering to that in a temple and enjoyed playing with children more than conducting Buddhist ceremonies. Sometimes, as in the hanging scroll One Hand Clapping (priv. col.; see Addiss, pl. 62), Hakuin showed Hotei standing upon his round bag with one hand raised, asking Hakuin’s famous ko-an, ‘What is the sound of one hand clapping?’ Hakuin believed that if one went beyond hearing, seeing, knowing or perceiving and meditated on this ko-an at all times, then reason and words would end, discriminations would cease and enlightenment could be found. When any of his followers solved this ko-an, Hakuin presented him with a painting of a Zen master’s staff and whisk as a ‘graduation certificate’. He would write the name of the follower and the date, and praise the heroism of the man who had struggled so hard to come to an awakening. Eventually Hakuin changed the painted staff into a dragon form full of energy and vigour.

During his 70s Hakuin began to experiment with ink. Instead of grinding it afresh each day, he used old ink on highly sized paper so that it produced puddling effects rather than being absorbed quickly. In this way he added tonal interest to his works, especially notable in the massive paintings and calligraphies of his final years. During his late period he concentrated on only a few major themes; his portrayals of Bodhidharma from this time are among the most forceful and dynamic in the history of Zenga. On these works he usually added inscriptions based on the words of the patriarch himself, as in the hanging scroll Daruma in Red (Manju-ji, O-ita): ‘Pointing directly to the human heart: See your own nature and become Buddha!’ In this riveting painting the powerful image of Bodhidharma has pronounced eyes and a bold red robe, and is set against a stark black background.

In his final years Hakuin also did several single-column calligraphies of phrases drawn from the doctrines of Zen and other Buddhist sects, such as the hanging scroll with the phrase Namu Amida Butsu (‘Praise to Amida Buddha’; Shin’wa-an priv. col.; see Addiss, pl. 59) from the Esoteric sect of Pure Land (Jo-do) Buddhism. This scroll was written in large blocky characters, easily readable by anyone but the totally illiterate. Using this form of visual sermon, Hakuin was able not only to teach and encourage all those he met but also to convey his own personality and character through brush and ink.

After Hakuin’s death, his pupils continued his traditions in Zen practice, teaching and art. Among his most notable students were To-rei Enji (1721–92) and Suio- Genro (1717–89). The Rinzai sect continues to be dominated by principles promulgated by Hakuin and his followers.

Stephen Addiss. "Hakuin Ekaku." In Grove Art Online. Oxford Art Online, http://www.oxfordartonline.com.proxy.lib.fsu.edu/subscriber/article/grove/art/T036198 (accessed May 3, 2012).

Person TypeIndividual