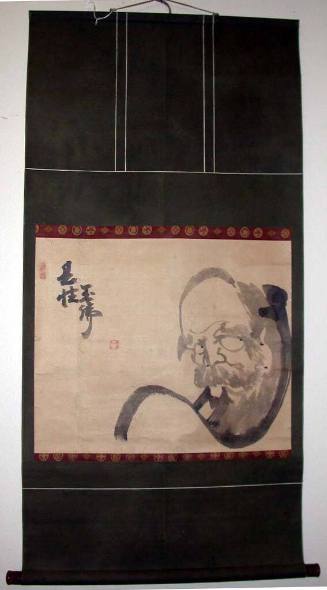

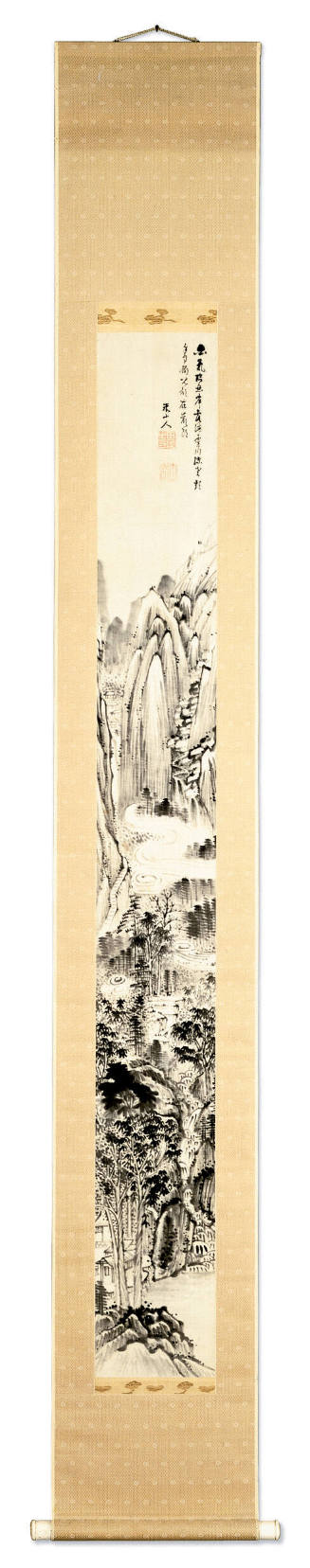

Ch'en Chi-ju (Mei Tao-jen)

Chinese, 1558 - 1639

Chinese editor, writer, calligrapher and painter. He exemplified the literati ideal of the accomplished gentleman–scholar who rejected the sordid world of political involvement and devoted himself to a life of literary, artistic and philosophical pursuit. At the age of 28, having passed the prefectural examination, the first important step leading to a career in government office, Chen renounced official life in a dramatic gesture, by burning his Confucian cap and gown. Thereafter he lived at country retreats at Kunshan and then Mt She, near Huating in Jiangsu Province: entertaining guests; writing and editing; composing the poems, prefaces, epitaphs and biographies for which he was in constant demand; and travelling to places of scenic beauty in the company of friends.

Chen followed the lead of his close friend Dong qichang, the foremost painter, calligrapher and connoisseur of the late Ming period (1368–1644), in admiring the Southern school of painting. His best-known book on painting and calligraphy, the Nigulu (‘A record of my love for the antique’), is a collection of short passages that evaluate the great masters of the past or comment on works seen at the homes of artists and collectors, who often invited him to append his colophons. In calligraphy, he modelled himself most closely on the Song (960–1279) masters, Su shi and Mi Fu (see Mi, (1)). By attempting to combine Su’s strength of brushwork with Mi’s brilliant variety of stroke, he succeeded in forming his own style of running script (xingshu), distinguished by its angularity and continual fluctuation between heavy and fine strokes, punctuated here and there by elongated horizontals set at a decided slant.

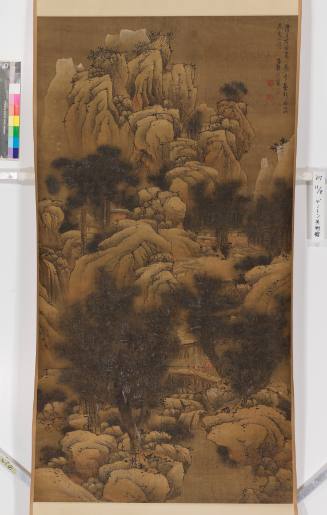

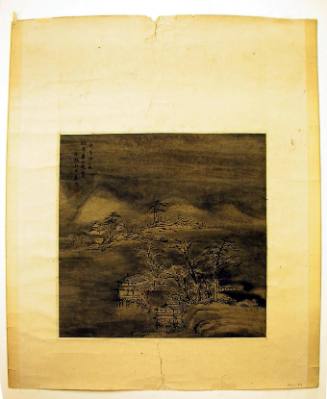

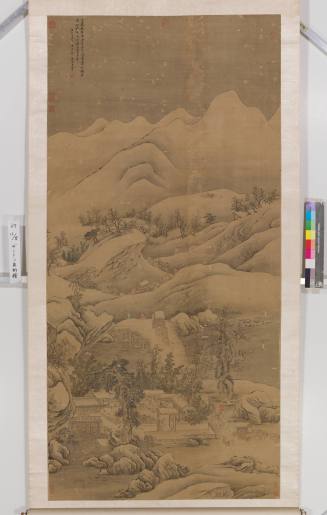

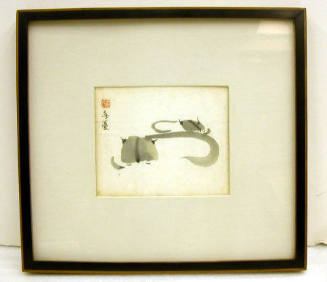

Among his paintings, notably of plums, his smaller compositions are the more successful: album leaves with a single branch engagingly captured within a small frame (e.g. Plum Blossoms, ink on paper; Kyoto, N. Mus.). His larger compositions are less skilfully contrived, their different elements failing to fuse into a well-structured and cohesive whole. The landscapes that go by his name are often in the loose, wet style associated with Mi Fu. The 20th-century art historian Xu Bangda maintains that they are all either forgeries or daibi (paintings executed for him at his own request by artists belonging to his circle, often with Chen’s genuine inscription and seals) and should be classed simply as products of the Songjiang (i.e. Huating) school.

Chen’s place in Chinese art history derives from his close involvement in the intellectual and artistic milieu of Huating, into which were drawn many of the most talented artists of his time, by whom he was regarded with special affection and admiration. So fond of Chen was Dong Qichang that he built a studio named Laizhong lou (‘Pavilion to welcome Zhong[shun]’); and a younger contemporary, the painter and calligrapher Huang Daozhou, wrote of him: ‘For noble aspirations and breadth of learning, there is no one to match Jiru.’

Celia Carrington Riely. "Chen Jiru." In Grove Art Online. Oxford Art Online, http://www.oxfordartonline.com.proxy.lib.fsu.edu/subscriber/article/grove/art/T016292 (accessed May 3, 2012).

Person TypeIndividual