Qi Baishi

Chinese, 1864 - 1957

(not assigned)China, Asia

Biographyb Xiangtan, Hunan Province, 1863; d Beijing, 1957.Chinese painter. He was probably the most popular painter in 20th-century China, esteemed alike by the conservative scholarly élite, the common citizens of China’s urban centres, foreign collectors and revolutionaries both artistic and political for his traditional paintings of birds, flowers, small animals and insects. The range of his appeal from the 1920s onwards derived from his character, his lifestyle and his image as a traditional, high-minded scholar–artist who remained aloof from corrupt politics and preserved cultural values during the politically and socially unsettled period after the fall of the Qing dynasty (1644–1911). Such an image may seem paradoxical given his humble social origins in rural Hunan Province and his early career as a carpenter; however, lowly beginnings and self-improvement through culture and learning were admirable according to Confucian standards, and by the end of Qi’s life the new Communist government had hailed him as an authentic ‘People’s Artist’.

Although without formal education, Qi acquired a deep knowledge of painting as well as calligraphy, poetry and seal-carving, all pursuits that defined the traditional Chinese literatus. He began to study calligraphy in 1896, using first 19th-century and then much earlier models, such as the work of Shen Zhou (15th century) and Mi Fu (11th century). He used a variety of styles, incorporating these in inscriptions on his paintings (see also China, §IV, 2(viii)). After establishing himself as a painter and seal-carver in his native Hunan, in his 40s he undertook a long series of travels, most significantly to Shanghai, where he was profoundly influenced by the scholarly but also innovative and popular Shanghai school and its leading master, Wu Changshi. At the age of 55 Qi finally settled in Beijing, where, in the more conservative cultural atmosphere, he established a close friendship with the literati painter Chen Shizeng (1878–1923), whose scholarly approach was a further influence on Qi’s art. Thereafter, Qi’s reputation grew enormously among Chinese and foreign collectors, to whom he catered with a prodigious output and a sharp commercial eye, though during World War II he refused to deal with the Japanese collectors who sought him out in occupied Beijing. This patriotism, along with his lower-class origins and status as a cultural celebrity, earned him respect in the People’s Republic after 1949, even when traditional culture in general was under attack. Elected to the National People’s Congress and made honorary Chairman of the National Artists’ Association, he represented a continuing commitment to traditional cultural values in revolutionary China.

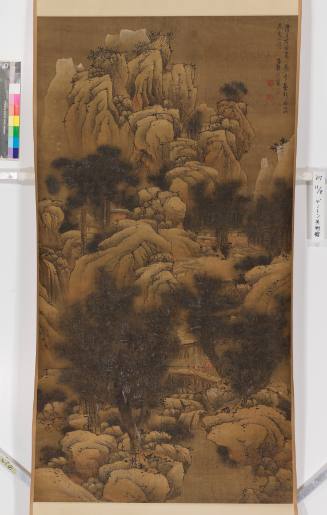

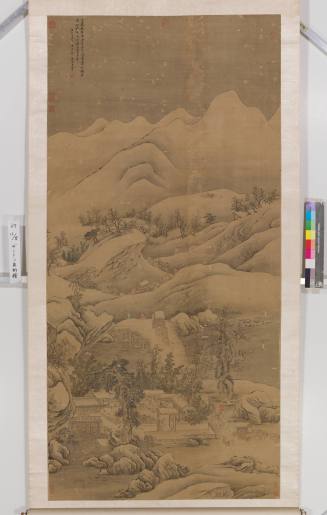

The subjects and themes of Qi’s paintings were derived directly from the later Chinese literati-painting tradition, showing no Western influences, stylistic or thematic. Yet Qi was a great innovator, who was praised by Xu Beihong, Wu Zuoren and other Western-trained painters for the freshness and spontaneity he brought to the familiar genres of birds and flowers, insects and grasses, hermit-scholars and landscapes. His compositions were often striking and original, in the manner of the 17th-century eccentric Zhu Da, while his free and untrammelled brushwork resembled that of the Ming-period (1368–1644) painter Xu Wei. Principally, however, it was his bold use of colour that lent vitality to his ‘small life’ studies. The subjects of these studies were often traditional motifs, such as pine trees or chrysanthemums, but Qi also painted more unusual, humble objects and creatures, such as crayfish , squirrels or lychees. Although he was not the first Chinese painter to focus on such subjects, by the end of his life he was the recognized master of the simple but profound study of common objects (see also China, §V, 1(iii)).

Qi’s style was continued by a number of painters in Beijing, Lou Shibai being perhaps the most notable, but for the subsequent development of Chinese ink painting his most significant influence may have been on Li keran who met Qi in the 1940s. Although the monumental landscapes of Li’s mature years departed drastically from Qi’s light touch, the older artist’s inspiration is obvious as his style evolved in the late 1940s and 50s.

Finally, in the florescence of ‘neo-literati’ ink painting that sprung up with post-Mao liberalization, Qi Baishi provided precedent and inspiration for the new era’s bolder experiments in personally expressive, semi-abstract ink painting. It is no exaggeration to note that Qi was not only the most famous Chinese artist of his time but also an important influence on the later era.

Ralph Croizier. "Qi Baishi." In Grove Art Online. Oxford Art Online, http://www.oxfordartonline.com.proxy.lib.fsu.edu/subscriber/article/grove/art/T070278 (accessed May 3, 2012).

Person TypeIndividual

Chinese, 1558 - 1639