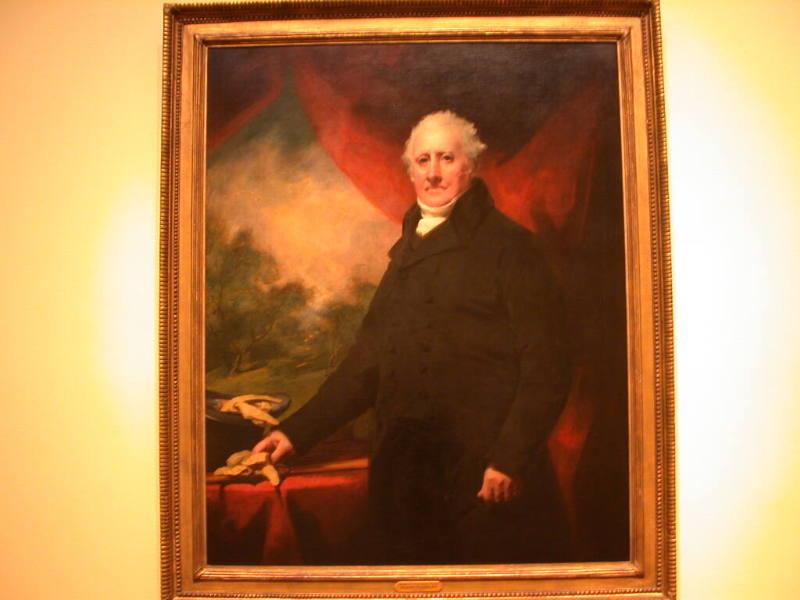

Sir Henry Raeburn

Scottish, 1756 - 1823

Scottish painter. He is perhaps the best known of all Scottish painters, with a critical reputation rivalling that of Allan Ramsay. He was almost exclusively a portrait painter, and his work did much to define Scottish society in a period of immense vigour and intellectual distinction. The demand for his work was sufficient to sustain a career wholly in Scotland, although he occasionally regretted his lack of first-hand knowledge of portrait painting in London. His working life, which was largely confined to Edinburgh, coincided with the Neo-classical expansion towards the north of the medieval city.

1. Edinburgh, 1756–84.

Raeburn was the son of Robert Henry Raeburn, who owned a business preparing yarn for the textile trade. He was born in one of a group of buildings that his father had erected a year or two earlier on the east bank of the Water of Leith at Stockbridge. By 1763 both his parents had died; two years later he entered George Heriot’s Hospital, Edinburgh, a school that had been founded in the 17th century for the education of tradesmen’s orphaned children. He was presumably supported by his elder brother William Raeburn, who continued the family business until his own death in 1810. Henry Raeburn may himself have played some role in the business in later life, because, even when established as Scotland’s leading portrait painter, he involved himself in business activities such as insurance broking and speculation in land and housing.

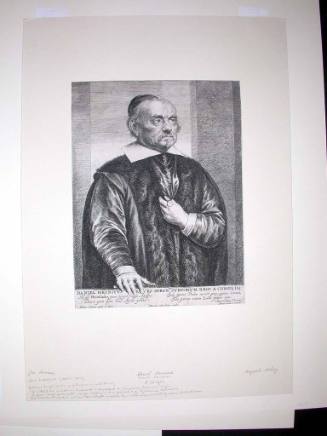

After leaving school in 1772, Raeburn began an apprenticeship with James Gilliland (Gillsland), a jeweller, with whom he probably lived. This was his first practical link with the world of art, both in the fashioning of the jeweller’s materials and in the trade’s links with the art of miniature painting. As early as 1773 (if a traditional date is accepted) he painted a miniature portrait of the seal engraver and etcher David Deuchar ( fl 1743–1808; Edinburgh, N.G.); it is carefully executed and convincing, though clearly a beginner’s work. While Raeburn’s portraits at the height of his career are marked by a consummate breadth of handling, they often contain passages of finely wrought detail that are easy to link to his earliest training. Tradition has given Deuchar the credit for turning Raeburn’s attention towards painting, but his precise steps in that direction remain a mystery. At this period the Trustees’ Academy, the usual training ground for any aspiring painter, held its classes in the old college buildings near Raeburn’s place of work, and he may have come into contact with its master, Alexander Runciman. Tradition also suggests a link with David Martin, the only real evidence of which is a copy by Raeburn of Martin’s portrait of Robert Cunninghame Graham (Edinburgh, N.P.G.), done a good deal later.

A painting with a good claim to being Raeburn’s earliest known full-scale portrait is the Lady in a Lace Cap (Edinburgh, N.G.). Although it is tonally high-keyed in an old-fashioned way, naively composed and generally reminiscent of David Allan’s work, passages of the costume show some of the wonderful facility of handling that distinguished Raeburn’s mature painting. This portrait shows some of the qualities that at this stage of his life would have justified him in contemplating seriously a career in painting and would have qualified him to receive the encouragement, from whatever source, that led him subsequently to undertake a journey to Rome. Two of his paintings that have been widely regarded as early works, belonging to the otherwise empty years between 1778 and 1784, are the three-quarter-length portrait of the geologist James Hutton (Edinburgh, N.P.G.) and the cabinet-sized full-length of the Rev. Robert Walker Skating on Duddingston Loch (Edinburgh, N.G.); the latter is now probably Raeburn’s most famous painting. James Hutton is an immature work; it is freely painted, and the clasped hands and the still-life of books and fossils are beautifully observed, but the sitter’s personality has hardly been engaged, and the picture is awkwardly constructed. However, the little portrait of the skater (the subject of which may have been wrongly identified) is formally much more advanced; the carefully considered outline of the profiled figure and the precise control of light and cast shadow have far more in common with Raeburn’s work of the early 1790s, and the work remains a subject of debate.

2. London and Rome, 1784–?1786.

By the time of his departure for Rome in the spring of 1784 Raeburn had already been married for a number of years to Ann Leslie, a widow of some substance, who brought him the property of Deanhaugh in Stockbridge. It was probably this kind of security that made the journey possible. His route was through London, where he may have stayed as long as two months, and tradition has it that he made contact with Joshua Reynolds. Although this is not certain, Raeburn’s portraits of the late 1780s, such as Colonel Lyon (Edinburgh, N.G.) and Admiral Inglis (Edinburgh, N.P.G.) show in their design Reynolds’s influence.

There is little secure evidence of how Raeburn used his time in Rome, although the chromatic values and high key of Colonel Lyon may hint at some knowledge of the work of Pompeo Girolamo Batoni, still active at this time. Contact with James Byres, the Scottish antiquary and guide, led to a commission from George, 2nd Earl Spencer for a miniature copy (Althorp House, Northants), by the pastellist Hugh Douglas Hamilton, of his portrait (untraced). Compared to the early miniature of David Deuchar, it is a work of some sophistication. Raeburn also came into contact with Byres’s nephew Patrick Moir, whose portrait (untraced) ‘by Mr Raeburn’ is recorded (Edinburgh, N. Lib., MS Dep. 184) as hanging in Byres’s apartments in Rome. The only other works of Raeburn’s Roman interlude are two small oils on paper: a draped classical female figure and David with the Head of Goliath (sold London, Christie’s, 25 May 1984).

3. Edinburgh, ?1786–1823.

In December 1785 Raeburn was reported to be about to start his return journey to Scotland by way of Paris. He was probably back in Edinburgh by the middle of 1786, and certainly well before the end of 1787, when he must have completed the portrait of Robert Dundas, Lord President (Arniston House, Lothian). During the 1790s he quickly established himself, working from a studio at 18 George Street in the centre of the New Town and pushing aside any competition on the part of David Martin. He developed a highly original manner based on directness of observation (as Byres is said to have advised him in Rome); it relied on a remarkably deft handling of the brush and a breadth of statement that became Raeburn’s hallmark, but sometimes led to accusations of lack of finish. Nevertheless, his portraits often contain areas of costume and still-life that are treated in remarkable detail, a reminder of the skills he had developed as a jeweller and miniaturist. He used no underdrawing, which contributed to the spontaneity and liveliness of his portraits; however, the process was never as simple as the finished surface might suggest, for X-ray examination of a range of Raeburn’s works has shown that especially in the heads, he initially explored the forms in a tentative fashion that belies the notion of a premier coup that did not need to be modified. The many radical alterations to outline must connect with his lack of practice in conventional draughtsmanship. He never drew from the naked figure, and his bravura handling occasionally fails to conceal weak articulation in his figures.

Raeburn’s masterpiece of the 1790s, perhaps of his whole career, is the double portrait in a landscape of Sir John and Lady Clerk of Penicuik (Dublin, N.G.; see [not available online]), which was exhibited in 1792 in John Boydell’s Shakespeare Gallery in London. It is a portrait of profound sentiment; the subjects have been given the ease and credibility that made Raeburn’s work so acceptable to his clients. Formally, it shows his interest at this time in effects of backlighting and sharply silhouetted shapes and of light defining the outline of dark areas, while spreading softly to the inner forms. These effects are found notably in two other portraits of the period: James Hunter of Blackness (Edinburgh, N.G.), which repeats on a life-size scale some of the morphology of the portrait of Robert Walker mentioned above; and the three-quarter-length portrait of William Glendonwyn (Cambridge, Fitzwilliam), which, again like Robert Walker, is a pure profile. Related to this phase, though in an entirely different medium, is the profile Self-portrait medallion modelled in wax and cast in ‘enamel paste’ in 1792 by James Tassie. Two other groups of works that share some of these features belong to the same decade of Raeburn’s career: a number of predominantly roseate portraits, often of female subjects, against rather vacuous landscape backgrounds; and the first in a great series of grandiloquent full-lengths in exotic costume with dramatic toplighting.

By the end of the 1790s the roseate portraits had given way to portraits with cooler colour schemes and a Neo-classical elegance. Among them was the supremely beautiful portrait of Mrs James Gregory (Fyvie Castle, Grampian, NT Scotland), where an early landscape background had been eliminated to great effect. The grandiloquent portraits included Nathaniel Spens, painted for the Royal Company of Archers (completed by 1793; Edinburgh, Archers’ Hall) and the rather later, brilliantly coloured image of a Highland chieftain, Sir John Sinclair of Ulbster (Edinburgh, N.G.). This type of portrait continued into the first two decades of the next century with the portrait of Colonel Alastair Macdonnell of Glengarry (c. 1811, exh. R.A. 1812; Edinburgh, N.G.) and The MacNab (Edinburgh, Distillers’ Co.), which greatly impressed Thomas Lawrence when it was exhibited at the Royal Academy in 1819 (though probably painted a good deal earlier). In the first of these portraits Raeburn adopted a much more intricate and descriptive style for the extensive areas of complex costume and accoutrements, while retaining toplighting, which was also a feature of the much more domestic (though still theatrical) portrait of William Forbes of Callendar (1798; Edinburgh, N.P.G.).

The fascination with sharply directed light was no doubt partly the result and partly the cause of Raeburn’s move to a new studio in a terraced house in York Place (‘built by Himself’, according to Joseph Farington, who called in 1801). The still extant painting room on the first floor features a greatly enlarged north-facing window with a complex series of adjustable shutters. The upper floor of the house acted as an exhibition gallery, where interested visitors could call, virtually at will. From 1809 Raeburn allowed these rooms to be used by the first exhibiting societies in Edinburgh. That he was able to set himself up in this way was a reflection both of his own prosperity and the increasing prosperity of that period, for he clearly foresaw that enormous demands would be made on him. However, a tendency to involve himself in commerce led to his bankruptcy in 1808; this brought him in 1810 to contemplate a move to London, in order to succeed to John Hoppner’s practice, but after a visit, he decided against it. By dint of hard work, in a situation where he had a virtual monopoly, he was in the end able to restore his fortunes, although he then occupied the York Place premises only as a tenant.

It was in these first two decades of the 19th century that Raeburn seemed to define Scottish society in its ‘Golden Age’, particularly in a series of seated, usually male, three-quarter-length portraits of great vigour and sympathy. They included the Charles Hay, Lord Newton (c. 1806; Dalmeny House, Lothian), where the rich abstraction of the legal robes in no way detracts from the compelling power of the head; and the near-romantic portrait of the antiquary and judge John Clerk, Lord Eldin (Edinburgh, N.P.G.). Raeburn’s productivity in this period was vast and, almost inevitably, very uneven in quality, suggesting, though without much evidence, that some of the least felicitous portraits must have been largely the work of studio assistants. His engagement with his sitters was never, however, simply in proportion to their eminence, for he painted many fine portraits of subjects far from the public eye, such as the outstanding pair of three-quarter-length seated portraits of James Cruikshank, a merchant in the West Indies trade and his wife, Mrs James Cruikshank (see fig.; both New York, Frick). These have a great naturalness; every flicker of the broken brushwork registers some nuance of appearance and personality, especially in the portrait of Mrs Cruikshank, who is seen from below, as if seated on the painter’s dais, and foreshortened with perfect calculation.

In 1815 Raeburn was elected a member of the Royal Academy in London. As his diploma piece he sent to London a Self-portrait (Edinburgh, N.G.), not realizing that self-portraits were not acceptable. It has a fine romantic fire, but the pentimenti and even a change of alignment of the canvas show that it caused him endless trouble; clearly he was anxious to impress a London audience. In a letter of 1819 to David Wilkie he bemoaned his remoteness from the major painters of the age and his inability to see how his work looked hanging next to theirs, and asked him to send news on a regular basis. In those years he seems also to have suffered a desire to emulate Lawrence, which resulted in a number of mannered, romantically charged portraits, where over-large eyes glisten and the head is thrown back in a kind of ecstasy. The most famous example is Mrs Scott Moncrieff (Edinburgh, N.G.), but these characteristics are seen at their most extreme in the portrait of Lady Gordon Cumming (priv. col., see Irwin and Irwin, 1975, p. 148), which Raeburn, surprisingly, considered the best female portrait he had ever done. This mannered tendency is also evident in one of Raeburn’s last portraits, a rather frontal head-and-shoulder image of Sir Walter Scott (Edinburgh, N.P.G.). The suggestion of a kind of apotheosis is perhaps the reason that Scott approved of it, unlike two earlier portraits. It brought together the greatest Scottish writer and painter of the age in a harmony they had failed to establish at their earlier meetings. Raeburn’s own achievement was marked in the summer of 1822, when he was knighted by George IV at Hopetoun House and given the vacant post of King’s Limner in Scotland.

Duncan Thomson. "Raeburn, Henry." In Grove Art Online. Oxford Art Online, http://www.oxfordartonline.com.proxy.lib.fsu.edu/subscriber/article/grove/art/T070538 (accessed May 2, 2012).

Person TypeIndividual